Abstract

This article provides an analysis of the Directive on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers of 25 November 2020. The Directive enables qualified entities to bring representative actions on behalf of the consumer. The article uses a Law and Economics approach to stress the advantages of collective actions as a tool to remedy rational apathy and free-rider behaviour. The article therefore in principle welcomes the fact that this Directive will lead to all Member States having some form of collective redress. However, it is rather difficult to fit this Directive into the economic criteria for centralization as there is no obvious danger of cross-border externalities or a race-to-the-bottom. The article is critical of the fact that the Directive only provides for a representative action and does not mention the alternative of a group action (sometimes referred to as a class action). This is especially problematic if there are very few qualified entities that could bring the representative action. Furthermore, the fact that Member States may choose an opt-in procedure instead of an opt-out procedure is critically evaluated. The most problematic aspect of the Directive is the funding of the representative action. Punitive damages and contingency fees are rejected, and the possibility of third-party funding is restricted. It is therefore to be feared that this Directive, notwithstanding the good intentions, may not lead to much application in practice, since the question of how the representative action is to be financed is not resolved in any satisfactory manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Consumer law is one of the domains where the EU legislator has been very active (Howells et al. 2017; Purnhagen 2013, pp. 498-499; Wagner 2011, p. 56). On the one hand, the EU strongly stresses the importance of public enforcement by the Member States, for example, in Regulation 2006/2004 on consumer protection cooperation (CPC-regulation OJ L364 of 27 October 2004). The CPC regulation forces Member States (MS) to create an EU-wide network of national enforcement authorities with similar investigation and enforcement powers (Faure and Weber 2017, p. 834). As far as private enforcement is concerned, Directive 2009/22 on injunctions for the protection of consumer interests (OJ L110/30 of 1.5.2009) provided the right for a “qualified entity” to file for an injunction for the protection of the collective interests of consumers. In addition, for a long time, there have been discussions on legislative action in the area of collective action (Voet 2014). A Commission Communication (COM(2013) 0401 final of 11.6.2013) “Towards a European horizontal framework for collective redress” summarizes the debates on collective redress in response to a 2012 Resolution of the European Parliament (European Parliament Resolution of 2.2.2012 “Towards a coherent European approach to collective redress”) and a Commission’s Recommendation (OJ L201) on common principles for injunctive and compensatory collective redress mechanisms in the MS concerning violations of rights granted under Union law. This 2013 Communication makes it clear that the search for a collective redress mechanism fits into a broader movement at EU level to award both citizens and businesses effective redress mechanisms in particular in cross-border cases, where the rights conferred on them by European Union law have been infringed. The Communication refers in that respect to the Directive on Consumer Alternative Dispute Resolution (Directive 2009/22/EC on injunctions for the protection of consumer interest, OJ L110, 1.5.2009) and to the Regulation on Consumer Online Dispute Resolution (Regulation No. 524/2013 on online dispute resolution for consumer disputes, OJ L165, 18.6.2013) (Wagner 2011, p. 57). Against this general background, the 2013 Communication already makes it clear that the Commission opted for a representative action for collective redress, with such an action being brought by a representative entity. The Proposals have meanwhile been further refined and have given rise to several comments in the legal literature (Ioannidu 2019; Van Duin and Leone 2019). Meanwhile the Directive on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers (2020/1828) was adopted on 25 November 2020.

Very briefly summarized, the Directive enables “qualified entities” to bring representative actions on behalf of consumers. In addition to consumer organizations and independent public bodies, qualified entities can also be designated on an ad hoc basis. A distinction is made between domestic and cross-border representative actions. Besides the already existing injunctions, the Directive introduces the possibility for redress orders, which can include compensation, repair, and replacement. Out-of-court settlement is promoted. The court or administrative authority has to assess the legality and fairness of the settlement, taking into consideration the rights and interests of all parties. We will discuss the Directive in more detail in the subsequent sections, where we provide a Law and Economics assessment.

The importance of collective action in the case of consumer claims has not only been highlighted in the Law and Economics literature, but also in the legal literature. Collective action can be a remedy in case of damage to common goods, mass torts, and scattered losses (Wagner 2011, p. 61). In consumer law, it is especially the latter problem that arises. It has more particularly been argued that, as a result of rational apathy on the side of consumers, small claims may not be brought (for legal literature about this argument, see, e.g., Hodges 2019, p. 60; Ioannidu 2019, p. 1370ff; Wagner 2011, pp. 62-63). This could result in a serious market failure as, taken together, the aggregated damage in all these small claims could represent a serious social loss. The Law and Economics literature has, moreover, paid a lot of attention to the optimal design of collective actions, inter alia in the light of earlier experiences with those claims at the domestic level, for example, in the Netherlands (Arons and Van Boom 2010; Purnhagen 2013, pp. 502-504). In this contribution, we try to answer the following research question: how does the Directive on representative actions for the protection of the collective interest of consumers compare to the economic starting points concerning collective redress, and can particular recommendations to policy-makers be provided in view of the transposition of the Directive? The method chosen to answer these questions is the economic analysis of law (Posner 2011).

We proceed as follows: First, we provide an overview of the literature concerning collective redress from an economic and a legal perspective. We then analyse critically why EU action in this domain is desirable in the first place. The core of the article consists of a Law and Economics assessment of the Directive. Finally, we conclude.

Collective Actions from an Economic Perspective

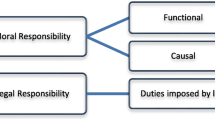

Introduction—Law as a Correction of Market Failures

Law and Economics scholars study law as a way to correct the various forms of market failures, i.e., market power, negative externalities, information asymmetry, and public goods (Butler et al. 2014, pp. 125-129; Pacces and Visscher 2011, p. 93-98; Rowley 1981, p. 401). Very schematic, market power is, for example, addressed by competition law; negative externalities are addressed by tort law, safety regulation, tax law, and criminal law; the main purpose of consumer law is to remedy information asymmetry, and intellectual property law addresses the public good problem present in “the production of information.”

For law to play this role, it has to be enforced. This can be done by public enforcement, but this contribution focuses on private enforcement. If a consumer is harmed due to, for example, a tort or a violation of consumer law, he can initiate a claim against the wrongdoer. This way, the wrongdoer is confronted with the negative consequences he has caused, and he is forced to stop the wrong behaviour, compensate the losses, deliver what he was obliged to deliver, et cetera. In the economics of accident law, the one potentially causing the harm is referred to as the wrongdoer (or the injurer/tortfeasor) as it usually refers to third-party liability for accidents. In the EU Consumer Law Directives, this actor is usually referred to as the “trader.”

Law and Economics is “prospective” (Butler et al. 2014, p. 33). That means that it primarily studies how legal rules will provide incentives to particular actors to behave. Obviously, there can also be an analysis of existing legal states of the world from an economic perspective, but there as well the central question is how legal rules will affect future behaviour. For the domain of tort law, damages are, from this prospective perspective, not primarily intended to compensate the victim of a wrongful act but to incentivize the potential wrongdoer to take desirable care measures in order to avoid the unlawful behaviour (Cooter and Ulen 2012; Shavell 2004; Wagner 2011, pp. 59-60).

There are several reasons why private enforcement may fail. First, filing a claim entails costs for the plaintiff, such as attorney fees and other legal costs, the time one has to invest, and the costs of the opposing party which one may have to pay if one loses the case (Wagner 2011, pp. 63-64). In addition, it may be difficult for an individual plaintiff to accurately predict the costs and the probability of winning at the trial. So, cost and risk aversion may reduce the incentive to file a suit. On the other hand, the optimism bias and over-confidence may influence the perception of the probability of winning (see generally Zamir and Teichman 2018, pp. 187-200). If the assessed costs outweigh the expected benefits of starting a claim, the potential plaintiff may remain “rationally apathetic.” Even in situations where a potential plaintiff would be certain to win the case, if his costs outweigh his benefits, he will not initiate a claim (Coffee 1984; Schäfer 2000; Wagner 2011, p. 64).This problem of rational apathy is especially pressing in situations of widespread or scattered losses, where many victims each suffer a relatively small loss, but the total loss caused by the wrongdoer is substantial (Wagner 2011, pp. 63-64). Situations of mass consumer losses (such as overcharging for mobile phone or credit card subscriptions) are examples of this.

Apart from the problem of rational apathy, individuals may act as free-riders: They wait for others to start a procedure so that they can benefit from the result without having to bear the costs of a procedure. However, if too many people wait for others, no procedure will be initiated in the first place. This problem is most pressing in cases where an injunction is sought, because the victims, who do not participate in the procedure and hence bear no costs or risks, fully benefit if an injunction is granted. However, the problem also appears in cases where damages are sought, because, as part of the collective action, legal and/or factual questions may have been answered, and the non-participating victims may use this information in their own subsequent individual trial.

A last possible problem is information asymmetry (Faure and Weber 2015; Van den Bergh 2013). If an actor does not know that he is a victim of a tort or of a violation of consumer law, or if he is afraid that he does not have enough information to be able to meet the burden of proof, he will not initiate a procedure and private enforcement fails.

Collective actions can potentially provide a solution for the problem that individual litigation will not take place due to rational apathy, information problems, free-riding, et cetera. Collective redress can, from a legal perspective, take a variety of different shapes (Purnhagen 2013, pp. 496-497). In the next sections, we will analyse the possible advantages and disadvantages of collective actions generally from an economic perspective. It will become clear that the institutional design of the collective action influences the advantages and disadvantages. An important distinction here is between “group actions” which are initiated by a person or group of persons in the name of a group of victims, so that individual claims are bundled into one collective claim (this is what in the USA is referred to as a class action) and “representative actions” which are initiated by a representative organization in the collective interests of victims (Deutch 2004; Miller 2013, p. 263; Viitanen 2007; Wagner 2011, pp. 61-66). We will give attention to those institutional details where necessary, but our main goal is to compare “collective litigation” in general with individual litigation.

Advantages of Collective Actions

The first advantage of collective actions is that there is only one collective procedure instead of multiple individual procedures. This implies that only one lawyer is needed instead of many, one case is initiated instead of many, the issues which are common to all individual cases only have to be investigated and decided once instead of many times, et cetera. With group actions, these costs are spread over the group of plaintiffs, and with representative actions, the representative organization may spread the costs over its members (Wagner 2011, p. 75). Because the costs and risks per person decrease with the increasing size of the collective, the problem of rational apathy is addressed (Hylton 2017; Keske et al. 2010, p. 59; Nagy 2019, p.10). Empirical research indeed shows decreasing costs per individual with an increasing number of participants (Eisenberg and Miller 2004).

Collective actions can also reduce the free-rider problem, depending on whether individuals who do not contribute to the collective action can still benefit from the outcome. A group action of which the outcome is applicable only to members of this group can indeed address the free-rider problem, because free-riders cannot fully benefit from the outcome, because they would still need to start an individual procedure. A representative action of which the outcome is applicable to all consumers, on the other hand, cannot adequately address this issue.

Furthermore, collective actions can ameliorate the information problems. In group actions, the costs of acquiring information are spread over many victims so that the costs per victim decrease. There are, in other words, economies of scale, which enable inquiries which would have been too costly in individual litigation. In representative actions, the advantage is that representative organizations are better informed about the applicable law, and possible infringements thereof, than individual victims. The representative organization may even be a specialist in the relevant field, which further lowers information costs. Unless they are set up only for one collective procedure, representative organizations are “repeat players,” which may provide a better balance in interactions with repeat-player firms than with the “one-shotter” consumer-victims (Galanter 1974). In both forms of representative action, due to economies of scale, it may be possible to employ lawyers who are specialized in the relevant field of law.

In addition, collective actions can make the total losses caused by the wrongdoer more visible. This may improve the deterrent function of law because the wrongdoer is now better confronted with these losses (Micklitz and Stadler 2006; Wagner 2011, p. 72). It also helps the court in determining whether the wrongdoer took adequate precautionary measures, because the possible losses are a relevant factor in assessing this.

Intermezzo: Opt-in or Opt-out?

The above-described advantages of collective actions depend, among other factors, on the group size and on how the group is formed. In order to overcome rational apathy and information problems, the group must be large enough to adequately decrease the costs per individual. In addition, if individuals can simply await the result of the collective action before they decide whether they want to participate, or if non-participants also benefit from the results of the collective action (e.g., an injunction), the free-rider problem is not solved. It is therefore important to analyse how the collective is formed.

In principle, there are three possibilities for this (Coffee 2000, pp. 376-380). First, all individuals could be included in the collective and could be bound by the outcome. In such a mandatory collective action, the group size is maximal, and free-riding is not possible. However, such an approach would be contrary to the principle of party autonomy (Nagy 2019). Furthermore, atypical victims who have suffered larger losses than foreseen in the collective action will remain under-compensated, which can result in under-deterrence (unless solutions such as damage scheduling adequately tackle this problem). Due to these issues, in reality, the choice is between two other options to form the collective: opt-in or opt-out (Keske et al. 2010, pp. 60-61). Potential participants could be required to express their desire to participate in the collective action, hence to opt in, or they are assumed to be included in the collective action, unless they have indicated that they want to opt out.

Economists tend to favour the opt-out model, especially because they fear that due to rational apathy and information asymmetry, only a few individuals would opt in (Tuil and Visscher 2010, p. 185). The (legal) argument that an opt-out model is contrary to party autonomy is, in our view, unconvincing, because due to rational apathy, this autonomy would not result in an individual claim anyway. In other words, the party autonomy, which is used as an argument against an opt-out model, will in many cases of small losses not lead to a claim as a result of rational apathy and would therefore de facto often be meaningless. The same rational apathy which in an opt-in model would result in too few participants, in an opt-out model results in a low drop-out rate (Eisenberg and Miller 2004). The collective therefore will be larger under the opt-out model, which enables the collective to reap the advantages described above. For example, economies of scale will be larger under opt-out, simply because the group is larger than under opt-in. So, with an opt-out model, rationally apathetic victims will not opt out, but they will be included in the procedure so that the defendant is better confronted with the losses he has caused. Only with an opt-out model will the rational apathy problem adequately be solved. That is why an opt-in collective action is generally considered inadequate for scattered losses (Wagner 2011, p. 78). And for party autonomy, it does not cause a problem either as individual victims who are not rationally apathetic can decide to opt out. Claims which depart too much from the average, e.g., because of much higher losses than average, can still be brought individually.

In the group formation, the timing is also of the essence. If individuals can first await the collective result before they decide whether they want to be bound by it (be it via an opt-in or an opt-out), the free-rider problem is not adequately tackled. Therefore, the opt-in or opt-out moment should not be placed too late in the procedure. On the other hand, if the collective action has yielded a result which clearly is inadequate for some individuals (e.g., those who have suffered higher losses than foreseen in the collective procedure), it is desirable for them to be able to start individual procedures to avoid under-compensation and hence under-deterrence (Coffee 2000, pp. 419-421). One possibility to combat free-riding is to increase the costs of individual litigation after a collective action has taken place, if the plaintiff had no valid arguments for not joining the collective action (Stigler 1974). But it should be kept in mind that in settings where, due to rational apathy, individual claims will not be initiated, the opt-out rate of a collective action will be low, so that the free-rider problem is limited anyway (Miller 1998, p. 260). This holds even more since collective actions will often be settled, so that they do not yield information that free-riders could subsequently use in an individual procedure (Schäfer 2000, p. 192). The extent to which the free-riding problem can be adequately remedied depends obviously also on the financing of the collective litigation and will, for that reason, also be addressed below when the various financing models of collective action are discussed.

Challenges of Collective Actions

A challenge which exists in individual litigation and which is exacerbated in collective litigation is the principal–agent problem (Wagner 2011, p. 72-73). In individual litigation, the lawyer is the agent who acts on behalf of his principal, the client. The agent/lawyer has possibilities of acting in his own interests also, instead of solely in the interests of the principal/client, because the latter has incomplete information and cannot fully monitor the former because monitoring costs are too high for this (DeMott 1998; Eisenhardt 1989; Hay 1997). In such an individual case, the client has better information and higher stakes (and therefore better options and incentives for monitoring) than individual participants in a collective action. This implies that the agency problems are even larger in collective actions than in individual litigation (Coffee 2000, pp. 378-379; Silver 2000, p. 215). Given that the lawyer or the representative organization in a collective action invests considerable resources in the case (such as time and money), it is to be expected that they expect a reward in return. Lack of monitoring by the principals (victims/consumers) enables these agents in collective actions to try to further their own interests, even if they are at the expense of those of the principals. The way in which litigation is financed has a strong influence on agency issues and therefore warrants a separate discussion below.

With representative actions, there is an agency relationship between the individuals who are represented and the representative organization on the one hand and between the representative organization and the lawyer on the other hand. This latter relationship may be less problematic than in a group action because the representative organization has better information and financial incentives to monitor the lawyer than individual plaintiffs have. On the other hand, agency problems between represented individuals and the representative organization increase in relation to the size of the representative organization and the range of the purposes it serves. After all, in such situations, there can be more conflicts of interests between the represented individuals (e.g., “all consumers” in the case of a general consumer organization), so that a representative action in fact may serve the interests of only a part of the consumers. This could, for example, be the case if there were a misleading advertisement which, in fact, only misled a relatively small number of consumers. If in that case a representative action were to be undertaken, it would lead to costs for all consumers, whereas the representative action would presumably benefit only a few. In addition, a general organization can better serve its own interests such as reputation, an increase in the membership, and more public attention than a specific organization aimed at a specific goal (Keske et al. 2010, p. 186; Miller 2013, p. 271; Schäfer 2000; Van den Bergh 2007). This disadvantage becomes especially pressing if the general representative organization has a monopoly. Competition between representative organizations would at least provide incentives to serve the interests of the represented individuals well, because they might otherwise go to a competing representative organization (Van den Bergh 2008, p. 294; Van den Bergh 2013, p. 30).

A possible way to mitigate agency problems is to impose restrictive conditions on collective actions, such as a merit test of the case or judicial review of the result achieved. Such a judicial review may address the information disadvantage of the victims vis-à-vis the lawyer or the representative organization, but it pre-supposes that judges can indeed adequately fulfil this role (Biard 2014). One may also pose requirements regarding, for example, expertise, representativeness, and credibility on the representative organization or the lawyer. For example, one could require representative organizations to be approved by a governmental body or a court or to have the goal of representing consumer interests in their articles of incorporation. Yet, the more conditions are imposed on the representative organization, the more entry barriers are created, and the less competition there would be. Competition between representative organizations is important as comparative pressure may drive down the price for consumers to participate in the organization and may increase the incentives of the organizations to compete with high-quality services to attract consumers. As such, between a limited number of representative organizations, there could still be competition, but if the number is relatively small, there is also a danger of collusive behaviour between them. One could also have a public body initiating the representative action, although the boundary with public enforcement then becomes blurred (Van den Bergh and Visscher 2008, p. 28).

A second challenge that is sometimes attributed to collective actions is the risk of frivolous suits and blackmail settlements (Hodges 2008, p. 4; Wagner 2011, p. 72). The fear is that plaintiffs would start unmeritorious collective claims in order to induce the defendant to settle. Such a settlement would be more attractive for the defendant than going to a trial. Even if the defendant did win (which may be quite likely in the case of a frivolous suit), he would still have to bear some litigation costs and possibly suffer reputational losses by the mere fact of being sued. The defendant could therefore be forced (blackmailed) into a settlement. It is, however, doubtful whether these problems really exist in practice (Hensler 2000; Hensler 2010; Ioannidu 2019; Miller 2013, p. 266; Nagy 2019, p. 37). Furthermore, it may not be the collective litigation, as such, that causes this (possibly only theoretical) risk, but the combination of other institutional characteristics of US-style class actions, such as contingency fees, punitive damages and the lack of a “loser pays” cost shifting rule (Nagy 2019, pp. 12 and 50).

Financing Collective Actions

Collective actions have to be financed, and, due to the problem of rational apathy, this cannot be achieved by asking small upfront contributions from the individuals who may ultimately benefit from the outcome of the procedure. Therefore, other ways of financing are required in which the agent (be it the lawyer in a group action or the representative organization in a representative action) bears the costs and risks of the procedure. The agent wants to recoup those costs from the proceeds of the case. A risk premium also needs to be added, to account for the costs incurred in cases that are lost and hence do not result in any proceeds.

Especially the impact of lawyers’ remuneration on agency issues has been studied in the Law and Economics literature. A full review of the literature falls outside the scope of our paper, but some general observations can be made (Faure and Visscher 2018; Keske et al. 2010). If one compares hourly fees (“HF”) with contingency fees (“CF”) or other forms of result-based fees, the literature generally argues that CF are better able to tackle agency issues between the client and the lawyer than HF, because the interests of principal and agent become better aligned. After all, with HF, the lawyer receives remuneration for every hour he puts in, irrespective of whether he wins the case. This may induce him to put too many hours in the case and also to litigate cases with a low probability of success. With CF, on the other hand, the lawyer is only paid if he wins the case so that he will not accept weak cases on a CF basis (Faure 2013, p. 43). Furthermore, the lawyer will not needlessly delay the case because this does not increase his remuneration.

Regarding settlements, a CF lawyer may accept a settlement offer quicker and for lower amounts than a HF lawyer, because he then receives a percentage of the proceeds without much effort. This may not be in the best interest of the client. On the other hand, a HF lawyer may reject a good settlement offer, because continued negotiations or even litigation increase the number of chargeable hours.

Empirical research suggests that CF results in better screening of cases on quality than HF (Helland and Tabarrok 2003), that fewer settlements are reached (because the CF lawyer tries to reach a better result in litigation from which he receives a percentage), but that if settlements are reached, they are reached quicker (because a CF lawyer does not benefit from delay) (Rickman 1999).

CF also provides a solution against rational apathy and risk aversion, because it is the lawyer who bears the costs and risks of the procedure, not the plaintiffs. Therefore, the fee will include a risk premium which covers the risk to the lawyer of spending costs on a case which he may lose.

Not only can CF address the financing problem of collective actions. A possible alternative is publicly funded collective actions. As mentioned before, the boundary with public enforcement then becomes blurred, and obviously agency issues arise here also. Subsidized legal aid may be another option, although it remains to be seen if this lowers the costs and risks of plaintiffs enough to overcome rational apathy. An especially important alternative is third-party funding (TPF). This is a system whereby a third party simply finances litigation costs against a payment which can consist of a part of the proceeds in the case of success (Solas 2019). When analysed from a Law and Economics perspective, it soon becomes clear that TPF serves similar goals to CF (De Mot et al. 2017). In CF, it is the lawyer who becomes the main risk-bearer and who will therefore act as a gatekeeper and ensure that only meritorious suits are brought. With TPF, these tasks are exercised by the third-party funder. From the plaintiff’s perspective, TPF has the same advantage as CF, namely that the costs and risks are not borne by the plaintiffs but by a better-informed party who can better bear and spread these costs (with CF the lawyer, with TPF the third-party funder). The main difference is that with CF, it is the lawyer himself who litigates the case and since his income is dependent upon success, his incentives are aligned with the plaintiff’s; with TPF the third party finances the claim, but litigation is done by a lawyer (who can still be paid on an HF). However, the third-party funder will also only gain in the case where the plaintiff wins, as a result of which the incentives of the plaintiff and the third-party funder are aligned. TPF is therefore able to address the rational apathy problem, but it in turn introduces similar agency issues as with CF. However, as with CF, the interests of the plaintiff and the third-party funder are better aligned than the interests of a client and a HF lawyer, because the funder only receives a reward if he wins the case. Therefore, TPF has similar effects on the quality of the case and the timing of settlements et cetera as CF. In both cases, the third-party funder or the lawyer will act as a gatekeeper and guarantee that only meritorious suits are brought. Moreover, in so far as the third-party funder is a repeat player who has gathered expertise in the relevant area(s) of law, TPF may also enable profiting from the benefits of CF in countries where the latter are not allowed (TPF is, e.g., actively applied in Belgium and the Netherlands, whereas these countries do not generally allow CF (Solas 2019, pp. 94-116)). The third-party funder can pay the lawyer on an HF basis but can monitor the lawyer better than the client. And because the client will only have to pay the third-party funder in case of success, rational apathy is tackled. Of course, agency issues between the client and the funder have to be addressed so that the funder cannot simply further his own interests at the expense of the interests of the client. But even with such agency issues, the possibility of TPF is better than the situation where there would be no litigation in the first place due to rational apathy, information asymmetry, et cetera.

With representative actions, funding can also take place via membership fees. The organization subsequently retains a lawyer, who is paid on an HF or on a CF basis. In so far as the representative organization is a repeat player, it is well able to monitor the lawyer, so that agency problems play a lesser role than with individual litigation. Therefore, the differences between CF and HF are less relevant here.

We will now turn to the Directive and first use the economic approach to ask the question of whether European centralization in this domain would be justified at all in order to subsequently provide a Law and Economics assessment of the Directive.

Is EU Intervention Needed?

Economics of Federalism

Before going into the Directive itself, it is useful to briefly ask the more fundamental question of why EU action in this domain would be needed at all. This question has already been addressed from a legal perspective (Hodges 2008, pp. 10-12; Purnhagen 2013, pp. 489-496) but has been dealt with in an elaborate way in the economics of federalism as well (Van den Bergh 2000). The terminology used in the legal and in the economic debate differs slightly. Economists refer to the question of centralization versus decentralization, whereas in the legal terminology, one usually refers to harmonization. Often the economic notion of centralization (meaning decision-making at a central level) de facto amounts to harmonization (approximation of the laws of the Member States), but that is not necessarily the case. Theoretically decision-making could be transferred to the central level, but there it could be decided to adopt differentiated rules. For the sake of simplicity in this context, we equate the economic notion of centralization with the legal notion harmonization.

The starting point of the economic approach is that legal diversity is in principle desirable, because different people in various MS may have different preferences regarding the goals of law. Diverging social norms may affect what is regarded as desirable and acceptable behaviour. Competition between legal orders may, moreover, have the benefit of offering diversified legal rules which correspond more closely to the preferences of the citizens (Tiebout 1956). Legal diversity moreover enables mutual learning. The mere fact that different MS have, for example, various solutions to the rational apathy problem may help MS in finding a better solution for their own legal system (Van den Bergh 2000, pp. 437-438). In a harmonized legal system, those benefits of the differentiation of legal rules according to preferences and the possibility of learning effects would be lost (Ogus 1999, pp. 415-416). From this perspective, one can argue that legal diversity, also with respect to rules concerning collective action, may be desirable as it corresponds to differing preferences. However, given the advantages of collective actions which we have discussed above, it is important that all MS have some form of collective redress. After all, there may be homogeneity of preferences in the EU, as far as the effective enforcement of consumer rights in every MS is concerned. From that perspective, it is positive that the Directive indeed requires MS to have at least one form of collective redress. The legal solutions can vary considerably depending upon the specific situation in one particular country as a result of which, from an economic perspective, there are no strong reasons in favour of harmonizing procedural law generally or collective redress in particular (Visscher 2012a, pp. 84-88).

Cross-Border Externalities

The first classic argument in favour of harmonization is the existence of transboundary externalities. States may have no incentive to impose stringent regulations upon their own businesses if the consequences of harmful actions are mostly felt outside their own territory. An example would be the regulation of transboundary pollution in a border area, where most of the pollution affects a downstream state. Transboundary externalities may thus create inefficiencies in the absence of central regulation (Revesz 2000, p. 67). This argument may favour centralization, for example, with respect to transboundary torts, but not for private law or procedural issues (Van den Bergh 1998, pp. 143-146). For the domain of collective redress, the argument does not stand, either from an economic or from a legal perspective. From an economic perspective, it would only be an argument if, say, MS A made a very strict regulation prohibiting any collective redress which would also harm victims in MS B that, supposedly, would suffer harm, for example, from products that cause harm in MS B. But the example immediately makes it clear that MS A would (even if it made a totally inefficient restrictive regulation on collective redress) never be able to protect its own industry for the simple reason that, if products or services were delivered to another MS (in this hypothesis MS B), the producer would still be liable in the export market (B) and an externalization of harm could therefore not occur (Faure 2000; Van den Bergh & Visscher 2006, pp. 518-519). From a legal perspective under the Rome I Regulation, consumers are entitled to the protection afforded by their domestic law (Regulation No. 593/2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations (Rome I), OJ L177, 4.7.2008, pp. 6-16, Art. 6 and recital 25). Therefore, whatever State A legislates cannot harm consumers in State B. This is, moreover, reinforced by the fact that under the Brussels I Regulation, consumers are entitled to bring a lawsuit in their domestic courts (Regulation (EU) No. 1215/2012 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, OJ L351, 20.12.2012, pp. 1-32, Art. 18) (also see, e.g., Tang 2011; Stadler et al. 2020). Moreover, the problem with the current Directive is that it not only applies to cross-border actions, but it is explicitly stated that it will apply to injunctions and redress measures at the domestic level as well. In other words, the cross-border externality cannot, either from an economic or from a legal perspective, constitute a justification for EU harmonization.

Race-to-the-Bottom

Centralization has been advanced as a remedy for the prisoners’ dilemmas that could arise in the case of a race-to-the-bottom: The assumption is that local governments would use lenient regulation as a competitive tool to attract industry. The validity of this race-to-the-bottom argument is strongly debated among Law and Economics scholars who argue that the argument neglects the benefits of differentiation (making legal rules corresponding to differing preferences) and that empirical evidence of the race-to-the-bottom (that states would try to attract industry with lenient regulation and that industry would respond to that with capital movement) is often lacking (Revesz 1992). It is very difficult to argue that states would attract industry with lenient rules regarding collective redress (Van den Bergh 2000, p. 445; Visscher 2012a, pp. 80-82). What one can only observe is, at best, a competition whereby some states (like the Netherlands) try to be a front-runner by organizing generous collective redress and thus also attracting transboundary claims to their jurisdiction. But that could be qualified as a race-to-the-top rather than as a race-to-the-bottom.

Levelling the Playing Field

An argument often advanced in the European context (more particularly within internal market law) is that all types of legal rules have to be harmonized in order to level the playing field for industry. The argument assumes that uniformity of legal rules would be necessary for the functioning of the common European market. This argument is a fallacy in the sense that a single market only requires a free flow of products, persons, capital, and services, but not necessarily a complete harmonization of all possible legal rules, let alone of legal procedure (Visscher 2012a, pp. 84-88). That is also the reason why, in practice, many Directives aim at minimum harmonization rather than at uniformity. Many European instruments can often not reach total harmonization for the simple reason that the costs of uniformity are apparently considerable (in that sense also Smits 2005, p. 178). As a result, many EU Directives often come on top of the (diverging) domestic legislation and therefore do not create uniformity. That therefore undermines the level playing field rationale. This is, incidentally, also the case in the current Directive. Article 1(2) of the Directive explicitly states that “this Directive does not prevent Member States from adopting or retaining in force procedural means for the protection of the collective interests of consumers at national level.” There may be reasons (of consumer protection but also of coherence of the national procedural framework) to make this choice, but it unavoidably implies that existing differences also remain as a result of which the Directive cannot create harmonization of marketing conditions.

Subsidiarity?

On the basis of this brief look at the economic criteria for harmonization, it seems obvious that this Directive, aiming at harmonizing representative actions for the protection of the collective interest of consumers, cannot fit into any of the economic rationales for harmonization. However, that obviously does not mean that it is, as such, a bad thing to regulate collective redress at the EU level. There are other arguments for this EU action than economic motivations (such as maintaining a high level of consumer protection in the Union), and from an economic perspective, it could also be argued that it is, as such, desirable that every MS has some form of collective action in order to cure the rational apathy problem. Especially in the case of those MS that, as yet, do not have any collective redress, the mere fact that the Directive at least guarantees that there will be some form of collective action possible may be important to cure the market failure caused by rational apathy. The added value of the Directive is then that it guarantees collective redress in all MS, not that it harmonizes the way in which that collective redress is organized. But two comments can still be made in that respect: First of all, from the perspective of subsidiarity, the Directive should have provided a better rationale than it does for why EU action is considered desirable. Recital 76 of the Directive merely states that the result of protecting the collective interest of consumers in order to ensure a high level of consumer protection across the Union and the functioning of the internal market “cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, but can rather, by reason of the cross-border implications of infringements, be better achieved at Union level.” But the problem is that this is merely a repetition of the subsidiarity principle as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty of the European Union, without explaining why this action could not be taken by the MS and would have to be taken at EU level. Moreover, it remains strange that the motivation refers to the cross-border implications of infringements, whereas the Directive does not only apply to cross-border cases, but also to those only having a domestic impact. A second point is that one has to recall that procedural differences between MS remain large as a result of which it remains difficult to lay down the details of a collective redress procedure to be followed in all MS in a harmonized manner (Visscher 2012a, pp. 84-88). Still, one could say that the devil is in the detail. In other words, the real effectiveness of a collective redress mechanism depends on the precise design and on the specific details (such as opt-out rather than opt-in and financing). It is for that reason that in the next section, we will now focus on the way in which those details are shaped in the Directive.

A Law and Economics Assessment of the Directive

Introduction

Even though we made it clear that standard Law and Economics justifications may not justify a European intervention, it has become equally clear that collective actions as such are regarded positively from an economic perspective and that an effectiveness argument could thus justify EU action. Therefore, in this section, we will apply the insights from the above analysis to the Directive. Even though we have argued that it is doubtful whether collective actions should be regulated at the European level in the first place, above it became clear that collective actions as such are regarded positively from an economic perspective. Therefore, if the Directive introduces the possibility for collective actions in MS which otherwise would not have this option, that in itself is a positive result. The Directive aims to ensure that at least one form of representative action is available in each MS. If there are more mechanisms in place, the representative organization can choose which procedure to use (Recital 11 and Article 1.3). Assuming that a representative organization will choose the available procedure with the highest chance of success, the Directive in essence provides a “minimum standard for collective actions.” The above analysis showed that the effectiveness of collective actions strongly depends upon the specific institutional design. In this section, we therefore investigate the extent to which the Directive is in accordance with the economic desiderata.

Goal and Main Features

The main goal of the Directive is to ensure that at least one representative action procedure for injunction and redress measures that corresponds to this Directive would be available in all MS (Recital 7). The Directive seeks “to improve the deterrence of unlawful practices and to reduce consumer detriment” (Recital 5). It tries to strike a balance between this protection of consumer interests, on the one hand, and the desire to avoid abusive litigation on the other hand (Recital 10 and Article 1.1). Clearly, this nicely fits the Law and Economics approach sketched above, where both the advantages (of improved deterrence) and the challenges (of, e.g., agency problems) of collective actions were discussed. The Directive encompasses many more areas of consumer law than the “Injunction Directive 2009/22/EC” it replaces (Recitals 13-18 and Article 2.1). This is obviously a good point because collective actions now become available in more areas of law than before. Moreover, the injunction procedure has the disadvantage that it does not provide compensation. As a result of the Directive, compensation for consumer harm will be widely available.

The Directive explicitly refers to problems of rational apathy, risk aversion, and information asymmetry as raisons d’être for collective actions, because they should “overcome the obstacles faced by consumers within individual actions, such as the uncertainty about their rights and available procedural mechanisms, psychological reluctance to take action and the negative balance of the expected costs and benefits of the individual action” (Recital 9; Nagy 2019, p. 10). Even in situations where individual actions would be feasible because the interests are high enough to overcome rational apathy, collective actions still have the advantage of reducing overall administrative costs. After all, one collective procedure is less costly than many individual ones, because the questions which are identical in the individual cases can be answered for all cases at the same time. Regarding information asymmetry, the Directive allows the representative organization to request the court to order the defendant to disclose information which is relevant for the claim and vice versa (Recital 68 and Article 18). This makes economic sense, because it requires the “least cost information provider” to actually provide the information. This reduces both the costs of acquiring information and the error costs which would occur if the necessary information did not become available.

Above, we explained that a collective action can consist of either a group action (where a lawyer represents a group of plaintiffs) or a representative action. The Directive harmonizes only representative actions and does not even mention the group action at all. That is noteworthy, as a representative action better fits collective litigation in situations where no individual would have legal standing (such as in cases of diffuse pollution). Given the absence of individual claims, a group action would be impossible. But for consumer interests, the optimal mechanism of collective redress is usually the group action. The main disadvantage of a representative action is that the representative organization is usually very broad and general, as a result of which the organization may pursue its own interests, possibly at the expense of that of the members which it represents (Schäfer 2000, p. 198; Van den Bergh 2013, p. 29). It is in that sense surprising that the Directive does not even mention group actions as they are considered to be better suited to address mass consumer losses than representative actions (Wagner 2011, p. 75-77, however, is also in favour of representative actions of consumer association for scattered losses). Agency problems may be larger with general representative organizations. In some countries, representative actions are also brought by monopolies (consumer organizations) which do not necessarily represent the interests of the entire group of consumers, but rather of a particular segment (Keske et al. 2010, pp. 67-72). It was probably the fear of the American type of class actions (probably instrumentalized and inflated by industry lobbying) that influenced the drafters’ decision not to introduce the option of group actions in the Directive. It is a pity that in this respect, the Directive gave in apparently to industry lobbying as group actions are generally considered a far more effective remedy for consumer redress than representative actions (Faure 2013, pp. 48-50). The extent to which this is a serious problem depends of course on the nature of this representative organization.

Qualified Entities

According to Article 4.1 of the Directive, MS “shall ensure that representative actions as provided for by this Directive can be brought by qualified entities designated by the Member States for this purpose.” The representative organization therefore has to be listed as a “qualified entity” (Article 4.3). On the one hand, this allows a quality check (e.g., that they are legal persons, have a certain degree of permanence, have a statutory duty in protecting the consumer interest, et cetera), which was regarded positively in the above analysis because it combats agency problems. On the other hand, this increases the market power of such entities, which could be problematic. For example, the requirement that, for cross-border representative actions, the entity can demonstrate at least 12 months of actual public activity (Article 4.3) seriously reduces the number of possible representative organizations and increases the market power of incumbent consumer organizations. The problem is that those requirements constitute de facto barriers to market entry and may therefore restrict the number of qualified entities that could bring the representative action. The number of qualified entities that could bring such an action will anyway be limited, as not many entities may have the funding to start the litigation. Of course, incumbent consumer organizations may have reputational incentives to act in the interests of their members. But, as indicated above, there is a danger that without sufficient competition, qualified entities may lack the necessary incentives to optimally defend the interests of all their members in a representative action.

An organization that wants to bring a representative action has to be listed as a qualified entity. This implies that the above-mentioned quality checks are done before the procedure starts, and this could in theory reduce the risk of blackmail settlements. After all, it is doubtful whether an organization that wants to file a frivolous suit in order to extract a blackmail settlement will be able to meet the criteria to be listed as a qualified entity. The requirement that qualified entities have to provide sufficient information regarding questions of fact and law and that the court should verify at the earliest possible stage of the proceedings whether the case is indeed suitable for being brought as a representative action, given the nature of the infringement and the losses (Recital 49 and Article 13), also makes economic sense. It reduces the risk of blackmail settlements because an organization that wants to achieve this will not be able to provide the information required to convince the court that a representative action is opportune. The possibility for the judge to dismiss “manifestly unfounded cases at the earliest possible stage of the proceedings” (Recital 39 and Article 7.7) also reduces this risk. In addition, the administrative costs are reduced because such frivolous suits are terminated quickly, even before the collective procedure has truly started.

The Directive specifically mentions consumer organizations and public bodies as possible qualified entities (Recital 24). Given that both are general organizations (representing a large variety of consumers), agency issues can play a large role here. The Directive also allows qualified entities on an ad hoc basis for a specific domestic representative action, although it is not encouraged (Recital 28 and Article 4.6). It is surprising that this is only possible for domestic actions and that no further criteria concerning the recognition of these ad hoc qualified entities are mentioned in the Directive. Qualified entities must have a non-profit character, at least for the purpose of cross-border representative actions (Recital 25 and Article 4.3). This requirement is likely to be based on the assumption that non-profit organizations (and public bodies) serve the general interest better than for-profit organizations (Nagy 2019, pp. 63 and 95). In our opinion, this is a naïve view, because non-profit organizations and public bodies may also have interests of their own (different from making a profit) which they can try to further at the expense of their principals. What is ultimately important is whether the agency problems are adequately addressed. A non-profit consumer organization that tries to increase its public exposure or its influence on policy, via a representative action in which it does not adequately serve the interests of the consumers, is in our view more problematic than a for-profit organization that tries to yield a profit by maximizing the result for the consumers it represents.

As mentioned before, the stricter the requirements that are posed on the qualified entities, the fewer the participants that will there be on the market, and as a consequence the less competition will there be between them (especially if, at least for cross-border suits, for-profit organizations are categorically excluded). Whether there will be enough competition between qualified entities depends on how many of such entities there are for consumers to choose from. In reality, there is often only one large consumer association per MS, as a result of which they often have a de facto monopoly. Here it is relevant that qualified entities can bring a so-called cross-border representative action in another MS (Recital 23 and Article 3.6 and 3.7). This somewhat reduces the risk of a monopoly in the market for representative organizations, although it remains to be seen how many foreign qualified entities would actually compete for a representative claim. The fact that qualified entities from different MS can join forces within a single representative action in front of a single forum (Recital 31) may even result in collusion between the qualified entities (e.g., only to focus in their representative action on harm that was suffered by one particular class of consumers). On the other hand, it reduces the administrative costs and increases the available information as compared to more representative actions in more MS. Moreover, the risk of collusion may not be that serious, as qualified entities from different MS are active on different geographic relevant markets and therefore not always competing. Cooperation may also be needed between the qualified entities to deal with local expertise and language. Also, the strictness of the quality criteria affects how many organizations can compete. In principle, the criteria applied to qualified entities should not hamper the effective functioning of representative actions. This is important as the criteria mentioned in the Directive itself (in Article 4.3) only apply to cross-border representative actions. Regarding qualified entities designated for the purpose of domestic representative actions, the Directive does not mention any criteria, but merely mentions that “Member States should be able to establish the criteria for designation of qualified entities for the purpose of domestic representative actions freely in accordance with national law” (Recital 26). But it continues “However, Member States should also be able to apply the criteria for designation laid down in this Directive for designating qualified entities for the purposes of cross-border representative actions in respect of qualified entities designated only for the purpose of domestic representative actions.” Although this provision is certainly not crystal clear, it seems that the drafters would also like the MS to apply the criteria mentioned for cross-border actions in respect to qualified entities acting only for the purpose of domestic actions.

The qualified entity has to provide sufficient information on the consumers concerned so that the court can establish its jurisdiction and the applicable law (Recital 34). This makes economic sense, because the qualified entity has already collected this information, so that it is the “cheapest information provider.”

The Directive also requires the qualified entity to act in the interests of the consumers (Recital 36 and Article 7.6). This requirement re-emphasizes the desire to solve the agency problems surrounding representative actions. Interestingly, the Directive also allows MS to provide individual consumers concerned by the action with certain rights within the representative action. This, in theory, could limit the possibilities of the qualified entities to act in their self-interest, although rational apathy probably prevents individual consumers from becoming too active. The fact that individual consumers should not be able to interfere with the procedural decisions undertaken by the qualified entity can be understood as it could lead to insurmountable problems and conflicts between the different consumers represented by the qualified entity. That obviously raises the question of whether individual consumers can be considered sufficiently represented by the qualified entity.

Opt-in Versus Opt-out

Above it became clear that, from a Law and Economics perspective, opt-out procedures are to be preferred over opt-in procedures. The Directive leaves it to the MS to decide which procedure to follow (Recital 43 and Article 9.2). In our view, it would have been better to only allow opt-out procedures, because if MS choose an opt-in procedure, we fear that, due to rational apathy, the collective action will not function properly with the result that the collective action will not encompass enough victims. The idea of an opt-in collective action to deal with scattered losses makes no sense (according to Wagner 2011, p. 78). The risk of a failure is even increased now that MS who choose an opt-in procedure may require that some consumers opt in before the procedure actually can start (Recital 44). Rational apathy can therefore fully frustrate the collective action, if the required number of consumers is not reached.

The Directive also leaves it to the MS to decide the timing of the possible opt-in or opt-out (Recital 43 and Article 9.2). We think that consumers should not be allowed to simply await the result of the collective procedure before they decide whether they want to be bound by it, because then they may fully act as free-riders. This problem, however, is more pressing for group actions than for representative actions, because in the latter, the representative organization to a large extent acts independently from the consumers it represents. An opt-out possibility after a settlement is reached makes sense, in order to reduce the risk of bad settlements. An opt-out possibility after the court has determined the redress measure, however, should only be possible for victims whose losses are substantially larger than foreseen in the redress measure and for whom damage scheduling does not provide a good solution. But as mentioned before, in opt-out procedures, the expected drop-out rate is very low anyway, so that in practice the timing of the opt-out possibility is much less important than the choice of an opt-out procedure instead of opt-in. Furthermore, opting out of a settlement will not give the individual consumer information which he can subsequently use in an individual procedure, so that the possibility to free-ride on a settlement is limited to start with. The fact that a final decision establishing an infringement can be used as evidence in other procedures (Recital 64 and Article 15) lowers the administrative costs and reduces the rational apathy of plaintiffs in such other procedures. Of course, this advantage has to be traded off against the increased risk of free-riding, which we have mentioned before.

For consumers who do not live in the MS where the representative action is brought, an opt-in procedure is mandatory so that opt-out is not allowed (Recital 45 and Article 9.3). This makes sense. If an opt-out procedure was possible, a representative action could be brought on behalf of all EU consumers. Due to information asymmetry and rational apathy, especially the foreign consumers will not opt out but also will not collect their part of the redress measure, simply because they do not know about this representative action in a different MS. This problem can be somewhat alleviated via the use of social media, as a result of which consumers could be informed also about cross-border actions, but as not all consumers access social media, that may not be a perfect remedy either. The increased value of the case (viz., on behalf of all consumers) increases the risk of blackmail settlements. By requiring foreign consumers to opt in, this problem is avoided. In addition, if there are many foreign consumers harmed by a specific firm, it makes more sense to organize a representative action in the MS where those consumers live. That procedure can then be organized on an opt-out basis, if national law allows for opt-out.

Obviously, consumers have to be informed about the existence of a collective action and on the possibility to opt in or out. Consumers can only exercise their right (or collect a remedy) if they are informed about it. The Directive therefore rightfully addresses this issue by requiring the infringer to provide this information at its own expense, unless the consumers are already informed in another way (Recitals 58 and 62 and Article 13). If qualified entities are the ones who have to inform the consumers, they can recover the related costs from the defendant if the action is successful (Article 13.5). This nicely allocates justified costs to the defendant if he indeed acted in an unlawful manner, but to the qualified entity if the action was unsuccessful. This reduces the incentive to start a frivolous suit, but on the other hand, it may also reduce the incentive to start a claim which in itself is justified but where the chance of success was not 100%. However, this issue holds for all litigation costs which the qualified entity can only recover in case of success, and that connects to the topic of litigation funding, which we discuss in the next section.

Financing

Many Options…

The above analysis has already made it clear that the financing of collective actions is the most important issue as a pre-condition for the effectiveness of those actions. Collective actions are costly, and someone has to bear the costs and risks attached to the case. There are in theory, as we indicated, many possible techniques to finance collective actions. Those costs could be borne by the representative organization which initiates a representative action, and those costs could possibly be pre-financed out of membership fees of represented parties. If the case is won, depending on the legal system, the litigation costs may be shifted to the losing party (but, as a mirror image, if the case is lost, the costs of the prevailing defendant may be shifted to the representative organization). An alternative way is via third-party funding, where the funder bears the costs and the risks, in exchange for a part in the proceeds if the case is won. We have also discussed contingency fees, where the lawyer is the party who bears the costs and risks in exchange for a part in the proceeds. Different funding structures may create different incentives for the parties to enhance their own interests, possibly at the expense of the consumers’ interests.

... Not Used in the Directive

When reading the Directive, it becomes clear that there is considerable reluctance to allow precisely the financial constructions which may be required to enable collective actions. First, but not most importantly, punitive damages “should be avoided” (Recitals 10 and 42). Law and Economics scholars tend to view punitive damages as a way to combat rational apathy (Cooter 1982; Visscher 2012b), so that from that perspective, this prohibition is problematic. The Directive expresses the fear that punitive damages result in the misuse of representative actions, but as we have expressed above, this risk of frivolous suits and blackmail settlements in our view is exaggerated, and there are better ways in which this problem can be addressed other than by forbidding punitive damages.

One such way is the “loser pays” principle (also known as the English Rule) which ensures that the losing party bears (part of) the litigation costs of the prevailing party. This rule prevents representative organizations from bringing a weak claim for the sole reason of extracting a settlement, because (1) the defendant is likely to prevail and hence will not have to bear his litigation costs fully and (2) the representative organization is likely to lose and will then be confronted with its own costs and (part of) the costs of the defendant. This is an important difference with the American Rule whereby each party bears its own litigation costs, so that settling a frivolous claim may be cheaper for the defendant than going to court and winning the case (Nagy 2019, pp. 12 and 50). In the First Reading of the European Parliament of 26 March 2019, it was explicitly mentioned that the unsuccessful party should bear the costs of the proceedings unless they were unnecessarily incurred or disproportionate to the claim (First Reading recital 4). The draft in the version agreed upon at the Competitiveness Council on 28 November 2019 stated that the Directive should not affect national rules on this matter, as long as individual consumers do not bear the costs (Proposal 28 November 2019, Recital 13c). Thus, the degree to which litigation costs influence the problem of blackmail settlements in that version was affected by the cost shifting rule in place in the MS. In the end, the Directive in Recital 38 again states that the unsuccessful party should pay the costs of the proceedings incurred by the successful party but that individual consumers concerned by a representative action should not pay the costs of the proceedings (and incorporated in Article 12 of the Directive). Needless to say, we welcome this re-introduction of the English Rule.

In the First Reading of the European Parliament, contingency fees were explicitly regarded negatively. It was stated that lawyers’ remuneration should not create any incentive to litigation that is unnecessary from the point of view of the consumers. MS that do allow contingency fees should ensure that consumers can still obtain full compensation (First Reading recital 39a and Article 15a). The latter point ignores that in a system of contingency fees, the lawyer instead of the client bears the risk of losing the case and should receive an appropriate risk premium for that (Nagy 2019, p. 18). The point that remuneration should not lead to unnecessary litigation is of course valid, but as we have explained above, contingency fees may result in less litigation than hourly fees. After all, as a gatekeeper, a CF lawyer will screen cases on quality because he only is paid if he wins, whereas a HF lawyer is paid by the hour irrespective of whether he wins. The Directive no longer explicitly disapproves of contingency fees. However, due to the general reluctance in Europe to use contingency fees (Faure et al. 2010), it remains to be seen whether this financing option, which is viewed positively in the Law and Economics literature, will be used in practice.

Funding Solutions in the Directive?

The Directive mentions various ways in which the financing problem may be addressed. First, MS have to maintain, or aim to find, the means to ensure that qualified entities are not prevented from bringing representative actions due to the costs involved. Options such as limiting court fees, granting access to legal aid, and public funding are mentioned here, but MS are not required to finance the procedures themselves (Recital 70 and Article 20). Indeed, funding collective actions is one of the biggest hurdles, so this issue has to be adequately addressed. However, limiting court fees only addresses a small fraction of the costs and will not be sufficient. Granting access to legal aid may cover the costs of legal representation, but not the additional costs that a collective action will entail. Public funding in theory may cover all costs, but MS cannot be required to do this. It therefore remains to be seen if MS indeed will fully solve the financing problem. If not, it is very likely that a representative action will not be brought for the simple reason that no one might be willing to take that risk, given the lack of financing. Instruments such as punitive damages and contingency fees could play a very important role to guarantee appropriate incentives to bring the representative action (Ioannidu 2019, p. 1375ff). As mentioned above, however, the Directive explicitly rejects punitive damages, and contingency fees are scarce in Europe.

The Directive does not allow individual consumers to bear the costs of the procedure either, unless they have deliberately or negligently caused unnecessary costs. However, qualified entities are allowed to request modest entry fees or participation charges for consumers who explicitly opt in (Article 20.3). By limiting these fees to consumers who have opted in, the Directive enables the acquisition of some funding while avoiding problems with party autonomy in the sense that a consumer could be confronted with costs without providing any authorization to be represented (Nagy 2019, p. 19). In addition, it deters consumers from causing unnecessary costs. However, such modest fees from consumers who have opted in will never yield enough funding, so it does not solve the funding problem.

Third-Party Funding

Third-party funding can contribute to overcoming the financing problem, and the Directive allows this. However, TPF constructions where agency issues are especially problematic are forbidden. For example, third-party funders should not finance a representative action against a competitor or against a defendant on whom the funder is dependent (Recital 25 and Article 10). If conflicts of interest are confirmed, courts should be empowered to take appropriate measures, such as refusing or changing the funding, rejecting the legal standing of the qualified entity, or dismissing a specific action (Recital 52 and Articles 4.3(e) and 10). Such restrictions make economic sense. The situation where the funder is dependent on the defendant creates larger conflicts of interests than the situation where the funder is a competitor of the defendant. In the first situation, the interests of the funder are better aligned with those of the defendant than with those of the plaintiffs, which obviously is the most extreme form of a conflict of interest imaginable. In the opposite situation, the interests of funder and plaintiffs are better aligned, but the funder is not primarily interested in getting the best result for the plaintiffs, but for itself as a competitor of the defendant. This causes agency problems as well, so it is understandable that this is also prohibited. However, the formulation of the Directive that a funder should not have “an economic interest in the outcome” of the action overlooks the fact that third-party funders always have an economic interest. After all, they bear the costs and risks of the procedure and only receive a reward from this if the case is won. Hence, the funder by definition has an economic interest in the outcome of the case! This is not problematic, as long as this economic interest is well-aligned with the interests of the plaintiffs, namely, to get a good settlement or a favourable judicial decision. A perfect alignment of interests is impossible, unless the plaintiffs have sold their individual claims to the funder (Pinna 2010). In situations where the funder receives a percentage of the proceeds, the interests by definition are not perfectly aligned. For example, if a funder (or a CF lawyer for that matter) receives 30% of the proceeds, he compares the costs of additional investments in the case with 30% of the increase in the expected proceeds due to this investment. He will only make such investments if they cost less than 30% of the expected increase. However, for the plaintiffs, such investments are worthwhile as long as they cost less than 70% of the increase, so the interests are not perfectly aligned. What is important to realize is that without TPF, the collective action might not be brought to start with, because of the costs and risks involved. The situation with TPF and the limited agency problems are clearly preferable to the situation without TPF, where collective actions would not be initiated.

Funding Problem not Solved

In conclusion of this section, it is very doubtful whether the Directive provides a good solution for the funding problem (Mucha 2019, p. 224). Punitive damages, contingency fees, and third-party funding are restricted, and the alternatives provided by the Directive are not likely to yield adequate funding. The Directive suggests that MS have to solve the funding problem (undoubtedly the result of a political compromise), but at the same time, it rejects all the market-based solutions which could provide adequate funding or representative actions.

The following quote provides an adequate summary of the problem: “Unfortunately, European collective action laws have failed to settle or even address the problem of financing. On the one hand, they ruled out the American institutions that stimulated the operation of US class actions. On the other hand, they failed to replace these with appropriate substitutes (…) The biggest trouble is, however, that the European model, in essence, rules out the risk premium devices of US law, which are rather unpopular in Europe, anyway, while it fails to offer any surrogate. The function and effects of contingency fees and punitive damages are to provide a risk premium to group representatives, in order to compensate them for the risk they run in favour of group members. European systems scrap these legal institutions (…) without offering anything in exchange in order to tackle the problem of risk premium” (Nagy 2019, pp. 59, 60).

The question arises of whether any solution to the funding problem could be found in the redress mechanism, for example, by allowing unclaimed amounts to flow to the qualified entity. It should, however, be mentioned that funding opportunities in consumer law have been provided in the recent so-called Modernisation Directive (2019/2161). This Directive modified, inter alia, the enforcement provisions in several consumer law directives. It provides for the introduction of fines up to 4% of annual turnover. Recital 15 of this Directive reads “When allocating revenues from fines, Member States should consider enhancing the protection of the general interest of consumers as well as other protected public interests.” It would thus be possible for MS to set up a fund which would collect revenues from fines (or part of those revenues) as well as unclaimed amounts.

Redress and Enforcement

A very important aspect is that the Directive introduces redress measures (such as compensation, repair, replacement, price reduction, contract termination, or reimbursement of price paid) besides the already existing possibility of requesting an injunction (Recitals 8 and 37). As was explained above, the free-rider problem is especially pressing if plaintiffs can only sue for an injunction or a declaration that the conduct of the defendant was unlawful, because non-participating victims fully profit from such results without participating in the collective action. With the redress measures which are mentioned in the Directive, this problem is less severe, especially if the collective result only holds for those who have participated. The problem of rational apathy can also be better overcome with redress measures than with injunctions. An injunction would only force a trader to comply with its obligations but would not necessarily provide redress to an individual consumer (Mucha 2019, p. 220).