Abstract

Drawing from the resource-based view and transaction costs economics, we develop a theoretical framework to explain why small and large firms face different levels of resource access needs and resource access capabilities, which mediate the relationship between firm size and hybrid governance. Employing a sample of 317 venture capital firms, drawn across six European countries, we empirically assess our framework in the context of venture capital syndication. We estimate a path model using structural equation modeling and find, consistent with our theoretical framework, mediating effects of different types of resource access needs and resource access capabilities between VC firm size and syndication frequency. These findings advance the small business literature by highlighting the trade-offs that size imposes on firms that seek to manage their access to external resources through hybrid governance strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Large size gives a firm advantages relating to the greater availability of financial resources, organizational routines, and capabilities (Bercovitz and Mitchell 2007). Small firms can try to mitigate these resource disadvantages by gaining access to external resources through hybrid governance (Dyer and Singh 1998). Empirical studies have shown that small firms with limited resources benefit more from partnerships than their more affluent partners, even when controlling for firm age (Stuart 2000). However, large firms with more central network positions and alliance experience are posited to be more valuable alliance partners (Williamson 1985; Podolny 1994; Nooteboom et al. 1997; Stuart 2000). These valuable network-based assets of large firms increase the need to protect them, particularly when they consider exchange with small and unfamiliar firms. This addresses an important strategic dilemma that is neglected in the strategic management literature: small firms have a higher need to gain access to external resources through collaborative structures, but at the same time are also less attractive partners, which impedes an optimal access to external resources through hybrid governance.

The aim of this paper is to examine how firm size affects hybrid governance. The role of firm size in hybrid governance structures has received little attention in the literature and has been theoretically ill-defined. Building on the extended resource-based view that focuses on access to resources rather than control of resources and integrates the resource-based view with arguments from transaction costs economics (Lavie 2006), we develop a theoretical framework to explain why small and large firms face different levels of resource access needs and resource access capabilities, which differentiate their hybrid governance strategies.

To demonstrate and empirically validate our framework we use the context of Venture Capital (VC) syndication. VC syndication involves two or more VC firms taking an equity stake in an investment, either in the same round or at different points in time (Brander et al. 2002). The decision to syndicate an investment is not trivial: there are both substantial advantages and disadvantages. Resource-based theory emphasizes syndication as a means to gain access to greater resources. For example, syndication may allow VC firms to gain access to larger funds, improve and enlarge their set of investment selection, monitoring and value-adding routines, or improve deal-flow generated through reciprocation by syndicate members (e.g., Bygrave 1987; Manigart et al. 2006). On the other hand, VC firms may be less motivated to syndicate transactions if they believe that the advantages of syndication are offset by the increased risks or costs. Hybrid governance arrangements, such as VC syndication, may require more coordination and may be less adaptive than non-syndicated investments (Williamson 1991). Further, syndication partners may have different interests, which may bring about greater chances of conflicts (Wright and Lockett 2003). Finally, what makes the context of the VC industry particularly interesting is the vital role of networks, making network-based assets an important factor in VC syndication decisions.

The rest of the paper unfolds as follows. First, we explain how VC firm size affects the need and the capability for syndication, by advancing theoretical explanations for syndication that involve the need and the capability to gain access to complementary resources through hybrid governance. Second, we describe the data and outline our empirical methods. Third, we present the results of our analysis. Consistent with our framework, we find that resource access needs and resources access capabilities mediate the relationship between VC firm size and syndication frequency, and when these different mediating effects are taken into account, no simple relationship between firm size and VC syndication frequency can be assumed. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the results, the limitations of the study, and provide directions for a further research on firm size and hybrid governance strategies.

2 Firm size and VC syndicated investment

2.1 Resource access and syndicated investment

The resource-based view distinguishes itself from other approaches by taking the firm’s individual resources as the unit of analysis. The resources of the firm enable the generation of Ricardian rents and/or quasi-rents (Conner 1991; Peteraf 1993). Ricardian rents—which are generated by scarce or inelastic resources—do not depend on the presence of other resources and therefore are unaffected by the total size of a firm’s resource endowments (Mosakowski 2002). Quasi-rents exist when the best use of a particular resource requires the presence of another resource because of the complementary nature of the relationship between the resources. For example, a firm may create value from complementary resources by generating synergies, enhancing internal resources, and making available a wider range of opportunities available (Lavie 2007). If complementary resources are not equally available to all firms, resources can only be used within the firm in its second best use. As small firms have a smaller scale and scope of resources available (Bercovitz and Mitchell 2007), they can have a disadvantage in generating rents from internal complementary resources. Small firms can try to mitigate these internal resource disadvantages by gaining access to external resources through hybrid governance structures, such as syndicated VC investment.

The traditional resource-based view focused only on the intra-firm complementarities because it assumed ownership or at least control of resources as a necessary condition for appropriating rents. In the relational or extended resource-based view, this assumption is relaxed to the weaker condition of resource accessibility, which refers to the right to utilize and employ resources or enjoy their associated rents (Lavie 2006). A fundamental question addressed in our paper is how firm size will influence the access to external resources through hybrid governance arrangements. We argue that in order to unravel this complex relationship, we need to distinguish between the need and the capability to gain access to external resources through hybrid governance. Small firms have limited in-house resources and hence are more dependent on accessing resources from external parties in order to create respectively value from new resource combinations (Dyer and Singh 1998), a wider range of strategic opportunities (Barney 1991), and accumulation of knowledge and skills (Kogut 2000). However, previous studies indicated that large (Stuart 2000) and reputable (Gulati and Higgins 2003) firms are the most valuable partners in hybrid governance settings, and therefore small firms may be less capable to partner with other firms. Hence, the need and the capability for accessing resources are diametrically opposing potential explanations of the firm size and syndication frequency relationship.

Previous studies identified four critical factors for syndication in the VC industry: access to financial resources, access to management resources and deal-flow reciprocation (Lockett and Wright 2001; Manigart et al. 2006), and adaptive coordination efficiency (Wright and Lockett 2003; Cumming 2006). The first two factors relate to the need for access to resources by syndication, whereas the latter two relate to the capabilities to syndicate. We expand our arguments below.

2.2 Firm size and resource access needs

2.2.1 Access to financial resources

Syndication facilitates access to financial resources from other VCs, thus enabling larger investments and diversification of the VC firm’s investment portfolio across a wider range of industry sectors (Zacharakis 2002). De Clerq and Dimov (2004) found support for a financial resource-sharing rationale for syndication among 200 US-based VC firms over a 12-year period. Lockett and Wright (2001) and Manigart et al. (2006) further showed that the dominant motive for European VC firms to syndicate their deals is gaining access to financial capital through sharing financial resources.

From the perspective of financial resources, large VC firms have fewer incentives to syndicate (Manigart et al. 2006) as their size means that they have more access to internal financial resources and can create larger portfolios within which it is easier to diversify risk. Diversification is particularly difficult to achieve in VC investment because of the high threshold costs of setting-up a relationship with the investee (Lockett and Wright 2001). Evidence suggests that smaller VC funds indeed find it more difficult to achieve optimal diversification (Huntsman and Hoben 1980; Murray 1999). Thus, we expect that VC firm size will be negatively related to the need to gain access to financial resources through syndication.

-

H1: VC firm size is negatively related to the need to gain access to financial resources through syndicated VC investment.

2.2.2 Access to management resources

An important non-financial resource for a VC firm is the management expertise to select and monitor investments effectively and facilitate value creation by the investee company (Lockett and Wright 2001). The need to gain access to specific management expertise through syndication may particularly be important if VC firms try to expand their industry sector, investment stage, or geographical scope outside their normal range of investment activities (Sorenson and Stuart 2001). Syndication may provide access to the superior expertise of other VC firms, thereby improving the quality of selection and post-investment value adding and monitoring (Sapienza et al. 1996; Wright and Lockett 2003). Several studies support this access to management resources argument as a motive to syndicate (e.g., Sorenson and Stuart 2001).

The management resources of a VC firm are likely to be constrained by the scale and scope of its activities (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996; Bercovitz and Mitchell 2007). The larger the VC team of executives, the more likely it is that the VC firm will hire specialists that devote their time entirely to investments in specific regions, industry sectors, or investment stages. Large VC firms are less likely to need additional management expertise outside their scope of operations. Therefore, we expect that VC firm size will be negatively related to the need to gain access to management expertise through syndicated investment.

-

H2: VC firm size is negatively related to the need to gain access to management resources through syndicated VC investment.

2.3 Firm size and resource access capabilities

2.3.1 Deal-flow reciprocation

VC firms are unlikely to identify interesting opportunities outside their natural investment area (Sorenson and Stuart 2001). Syndication allows VC firms to do so by using inter-firm networks across geographic and industry boundaries (Manigart et al. 1994; Sorenson and Stuart 2001). Syndicating a deal may create an expectation to reciprocate the gesture in the future (Lockett and Wright 2001).

Large VCs are more attractive syndication partners because of their status (Stuart 2000), central network position (Podolny 1994) and larger scale and scope of operations. Large VC firms are therefore more likely to be invited into future deals. Previous research (Manigart et al. 2006) reported that deal-flow reciprocation is more important for larger early stage VCs than for smaller early stage VCs. Syndication may also improve the status, central network position, and range of activities of VC firms, and large firms may have the need to maintain and improve these firm resources and capabilities. However, small firms also have good reasons to improve these resources and capabilities (Hochberg et al. 2007). What differentiates large and small VC firms is that small VC firms are less likely to be invited in future deals, and therefore their capability for deal-flow reciprocation is less effective. Therefore, we expect that deal-flow reciprocation will be positively related to VC firm size.

-

H3: VC firm size is positively related to deal-flow reciprocation through syndicated VC investment.

2.3.2 Adaptive coordination efficiency

According to transaction cost economics (TCE), a fundamental problem of organizations is how to cope efficiently with an unpredictable environment when organizing transactions (Williamson 1999). Firms will prefer those governance forms that by approximation have the highest level of comparative adaptive coordination efficiency to unexpected future contingencies. VC firms can choose to bring resources under their own control and execute the transaction under “hierarchical governance” or achieve access to resources through “hybrid governance,” such as VC syndicates, where external resources become available to the syndicate partners without the formal transfer of ownership. A crucial assumption of TCE is that hierarchies are more efficient in adaptive coordination compared to hybrid governance arrangements (Williamson 1991), and so contracts within firms can be more incomplete than between firms. A capability can be defined as the ability to perform a particular task or activity (Helfat et al. 2007), and TCE’s claim that hierarchical governance is more efficient in performing adaptive coordination tasks or activities is based on five coordination capability advantages (Williamson 1991, p. 280):

-

(1)

Proposals to adapt require less documentation;

-

(2)

Resolving internal disputes by fiat rather than arbitration saves resources and facilitates timely adaptation;

-

(3)

Information can more easily be accessed and more accurately assessed;

-

(4)

Internal dispute resolution enjoys the support of informal organization;

-

(5)

Internal organization has access to additional incentive instruments that promote team orientation.

The comparative efficiency of hierarchical adaptive coordination may particularly apply in the context of the transfer of tacit knowledge and higher order routines. Examples in the literature are non-tradability of knowledge assets (Kogut and Zander 1992) and the more efficient utilization of tacit knowledge (Conner and Prahalad 1996). In addition, Williamson (1996) refers to the high costs of writing explicit contracts over knowledge routines compared to the continuous association between employee and manager. Hierarchical governance can efficiently enforce implicit elements of contracts, using the internal norms and conventions that emerge from continued interaction among employees. Overall, TCE as well as knowledge-based theory provide strong arguments that knowledge exchange within firm boundaries is more efficient than between firm boundaries. Empirical evidence of adaptive coordination inefficiency in syndicated investment is reported by Cumming (2006) and Wright and Lockett (2003). Cumming (2006) reports that syndication reduces portfolio size per manager and explains this effect by arguing that each VC firm manager must monitor other syndicated VC investors in addition to the portfolio companies. Wright and Lockett (2003) found that agreement on coordinated action and decision-making in the syndicate took longer than in non-syndicated investment.

The question that needs to be addressed in the present study is why firm size would influence the relative adaptive coordination efficiency of firms. Large VC firms with more specialized and experienced executive teams will attract more funds (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996), negotiate better deals (Hsu 2004) and have better access to capital (Laine and Torstila 2005). However, large firms owe such scale advantages to a complex system of repetitive and specialized routines (Barney 1997; Dobrev and Carroll 2003, p. 542). Any change in the system of routines requires successive steps in the organizational hierarchy until a common level of supervision is reached. This requires more time and in addition will be less effective because with each additional layer of hierarchical coordination, there may be considerable risks of distortion of information (Williamson 1967). Small VC firms, on the other hand, can operate with less complicated bureaucratic structures (Chen and Hambrick 1995; Forbes and Milliken 1999) with fewer decision-makers (Das and Husain 1993). Further, they can operate with fewer formal systems and procedures in place and perform fewer planning activities (Busenitz and Barney 1997). Less restrained by structural inertia (Hannan and Freeman 1984) and endowed with greater decision speed, smaller VC firms can adapt more efficiently than larger VC firms to unexpected future contingencies.

Furthermore, large firms have more exposure through public information (Nooteboom et al. 1997), and given the high visibility of the investment behavior of large VC firms due to their central network position and their higher exposure in the economy (Podolny 1994), large VC firms in particular are constrained by the risks of opportunistic behavior or bounded rationality of syndication partners, and need to invest more in extensive screening and monitoring (Stuart 2000) or limit their potential syndication partners to other prominent VCs (Lerner 1994; Stuart et al. 1999) or to known partners (Stuart 2000). In addition, because such measures are imperfect (Williamson 1985, p. 112), large firms will syndicate less, so as not to be exposed to potential syndication risks or face higher costs resulting from adaptation to (potential) coordination problems and conflicts. Thus, if the business environment is complex and uncertain—such as in the VC industry—we expect that the adaptive coordination efficiency of the focal firm in hybrid governance forms such as syndicated investment to be negatively related with firm size.

-

H4: VC firm size of the focal firm is negatively related to the adaptive coordination efficiency of a syndicated VC investment.

2.4 Control variables

We include several potentially size-related variables that may explain syndication frequency. First, in general early stage deals are more complex and uncertain than later stage deals (Sapienza et al. 1996); this may impact transaction costs and hence syndication frequency. Hence, we included investment stage as control variable. Second, large firms with their alliance experience and central network positions may be more likely to lead VC syndicates than small VC firms. We therefore included lead syndication as a control variable. The management of the investment is delegated to the lead investor, which increases the workload of the lead investor, but may reduce the risks of the lead investor. Further, we included firm age as a control variable. VC firm contacts, experience, and status are likely to grow with its age, and young VC firms may have a higher propensity to opportunistically strive towards successful exits (Jääskeläinen et al. 2006). Thus, many of the effects of firm size may be confounded with the effects of firm age, and we need to control for these effects.

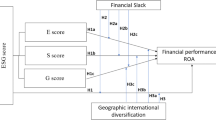

In Fig. 1, we summarize the model with the four hypothesized relationships, the control variables and the relationships with syndication frequency. In addition to the indirect effects of VC firm size, we also include the direct effects of firm size to control for direct effects of firm size on syndication frequency. Next, we discuss the data and the methods used to test the proposed theoretical framework.

3 Methods

We tested the above framework on a dataset of 317 European VC firms. The data were gathered using a pre-tested mail survey. The questionnaire was developed in three phases. The first stage in the process was the development of a questionnaire based on available literature (Lockett and Wright 2001; Manigart et al. 2006). The questionnaire was piloted in six interviews with a range of executives in VC firms involved in different stages of venture capital investment. We administered the questionnaire in six European countries, ranging from Northern Europe (UK, Sweden) to central countries such as France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The sample, therefore, includes countries in different parts of Europe, where the VC industry is long established and industry practices have matured (Manigart et al. 2006).

The questionnaires were translated into French and Dutch in order to be used in France and Belgium. The questionnaire was administered by post to the head offices of all 106 VC firms in the UK, identified using the British Venture Capital Association handbook and CMBOR (Center for Management Buy-out Research) records. In Belgium, data were collected by sending a questionnaire to 79 VC firms, identified using the membership list of the Belgian Venturing Association and the European Venture Capital Association. In France, data were collected by sending out 120 questionnaires to the full members of the ‘Association Française des Investisseurs en Capital Risque.’ In Sweden the questionnaires were sent to the 169 members of the Swedish Venture Capital Association and the VC members of the Swedish National Board of Technical and Industrial Development. In Germany and the Netherlands, the untranslated questionnaire was sent to the 191 members of the EVCA and 50 members of the Dutch Venture Capitalist Association. In all countries, a follow-up was done either by sending reminders or by calling the VC firms after 1–2 months.

The total sample consists of 317 usable responses (44% response rate) from the six European countries (63 UK, 66 Sweden, 49 France, 68 Germany, 29 the Netherlands, and 42 Belgium). As response rates and participation in syndication networks might be related, non-response bias of the sample was tested using the test of Armstrong and Overton (1977), and no significant deviation was found. In addition, the representativeness of the sample was tested for each country separately using firm-specific characteristics (minimum investment preference, maximum investment preference, and the number of staff members) available from the national and European VC directories. No significant differences were found between respondents and non-respondents in Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. In Sweden and the UK, the respondents’ maximum investment preference is significantly (5% confidence level) larger than that of non-respondents. This indicates that using several variables the sample is generally representative for the VC firm industry in all countries of the study, with the exception of maximum investment preference for Sweden and the UK.

3.1 Measures

3.1.1 Syndication frequency

To examine the empirical relationship between VC firm size and syndication frequency, we measure syndication activity in five categories: 0%–20%, 21%–40%, 41%–60%, 61%–80%, or 81%–100% of the total portfolio that is syndicated (measured in number of deals). The median VC firm in the sample has syndicated frequency between 41% and 60% of the deals in its portfolio (category 3).

3.1.2 VC firm size

Various options are available to measure firm size, such as the number of executives, the number of VC firm investments, or the funds under management (Cumming 2006). We have chosen the number of VC firm executives and the size of the funds under management as our size measures. Theoretically, both size measures are linked with each other. Large teams of VC executives are more likely to be specialized and therefore have better access to management resources. In addition, large teams are likely to have more status than small ones (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996) and therefore are more likely to have large funds under management. We did not combine the two measures in one model because of potential problems of multicollinearity. We log-transformed the size variables in our analysis, which reflects the idea that size has diminishing marginal effects. The rationale for the diminishing marginal effects for size is that we expect that relative changes are more meaningful than absolute changes in these variables. The effect of an increase in a VC firm’s number of executives with 10 employees might be substantial for a firm with 5 employees, while it will only be small for a firm with 500 employees. A change in a VC firm’s number of executives with 10% might have a similar effect for both small and large VC firms.Footnote 1

3.1.3 Resource access needs and capabilities.

We included scale items in the survey questionnaire to measure the degree to which different resource access needs and capabilities (see Table 1) were important in the decision to syndicate; these related to management, finance, and deal-flow reciprocation. [Survey question: How important are the following factors in influencing your decision to syndicate deals? (Please rate from 1 to 5, 1 = very important; 5 = very unimportant)].

3.1.4 Adaptive coordination efficiency

Empirical research on transaction costs economics almost never attempts to measure such costs directly, but instead uses indirect measures of transaction costs. Such indirect measures are asset specificity, frequency, and uncertainty (Williamson 1985). A risk of such indirect measures is that they can also be compatible with alternative explanations (Carter and Hodgson 2006). In this study we aim to measure transaction costs directly using the survey questionnaire scale items listed in Table 1. The theoretical foundation of our measure is the assessment of TCE that hierarchical arrangements have more efficient adaptive coordination capabilities as compared to hybrid governance arrangements (Williamson 1991). Compared to hybrid governance, coordination by hierarchical governance facilitates timely and efficient adaptation through lower information costs, dispute settlement, decision-making, and incentive systems (Williamson 1991). We do not include all (absolute) transaction costs of adaptive coordination because transaction costs economics is only interested in the comparative assessment of the costs differences between the discrete governance alternatives. This allows for cruder and simpler measurements than the absolute measurement of transaction costs (Williamson 1985).

3.1.5 Measurement validity

Survey respondents were asked to indicate on 5-point Likert scales how important they find the above items in their decision to syndicate deals. The scale items were first factor analyzed, using principle component analysis and varimax rotation. We analyzed the different dimensions of the scales to assess their unidimensionality and factor structure. Items were checked if they satisfied the following criteria: (1) items should have communality higher than 0.3; (2) dominant loadings should be greater than 0.5; (3) cross-loadings should be lower than 0.3; (4) the scree plot criterion should be satisfied (DeVellis 1991; Briggs and Cheeck 1988). One item did not satisfy these criteria, and this resulted in a pool of 15 items and 4 factors (see Table 2). The reliabilities of the dimensions of each scale were assessed by means of the Cronbach alpha coefficient. The alphas are 0.81 (need for management resources, five items), 0.72 (need for financial resources, four items), 0.83 (deal-flow reciprocation, two items), and 0.83 (adaptive coordination efficiency, four items). Furthermore, all items have correlations of 0.70 or more with their respective constructs, which suggests satisfactory item reliability (Hulland 1999).

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) with EQS version 6.1 to further explore the validity of the scales by adding constrains to the measurement model (Table 2). The constrained exploratory factor analysis obtained a satisfactory fit (χ2 = 112, df = 41, p < 0.01), root-mean-square estimated residual [RMSEA] = 0.06, Bentler-Bonett Normed fit index [NFI] = 0.92. The ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom is 2.73; a value of less than 3.0 for the ratio indicates a good fit (Carmines and McIver 1981). A NFI value above 0.9 is considered an indication of good fit, and the RMSEA of 0.06 indicates good model fit because it does not exceed the critical value of 0.08 (Bentler and Bonett 1980). Composite reliabilities are all above the 0.70 commonly used threshold value, and average variance extracted measures exceed the 0.50 value (Hair et al. 1998). Discriminant validity of the scales was further verified by comparing the highest shared variance between any two constructs and the variance extracted from each of the constructs. In all cases, the shared variance between two constructs was far less than the variance extracted from each of the constructs, supporting the discriminant validity of the measurement model (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Finally, none of the confidence intervals of the correlation coefficients between any two constructs contained 1.0 (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). Overall, thus, the measurement model is acceptable, given this variety of supportive indices.

3.1.6 Control variables

We measured Early stage as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the VC firm invests in early stage deals, and 0 otherwise. Of the VC firms, 60% in the sample indicated that they invest in early stage deals. We measured Lead syndication as the approximate proportion of deals (in five categories of 20%) in which the VC firm acts as a lead member, and we measured Firm age as the log-transformed number of years the VC firm has been in operation.

3.1.7 Common method bias

According to Podsakoff et al. (2003), common method bias can have substantial effects on observed relations between measures of different constructs. To address this problem we first performed Harman’s one-factor test on the self-reported items of the latent constructs included in our study. The hypothesis of one general factor underlying the relationships was rejected (p < 0.01). In addition, we found multiple factors, and the first factor did not account for the majority of the variance. Second, a model fit of the measurement model of more than 0.90 (see Table 2) suggests no problems with common method bias (Bagozzi et al. 1991). Third, the smallest observed correlation among the model variables can function as a proxy for common method bias (Lindell and Brandt 2000). Table 3 shows a value of −0.01 to be the smallest correlation between the model variables, which indicates that common method bias is not a problem. Finally, we performed a partial correlation method (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). The highest factor between an unrelated set of items and each predictor variable was added to the model. These factors did not produce a significant change in variance explained (p > 0.33), again suggesting no substantial common method bias. In sum, we conclude that the evidence from a variety of methods supports the assumption that common method bias does not account for the study’s results.

4 Results

A description of the survey items and the variables under study are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The need for financial resources is the most important factor in the decision to syndicate with a mean value of 3.79 (on a 1–5 scale). The need for management resources and deal-flow reciprocation are on average not seen as important factors in the decision to syndicate investment (2.57 and 2.73, respectively). Adaptive coordination efficiency of syndicated investment is considered to be relatively low by the respondents (mean 2.18). This strengthens our argument that adaptive coordination efficiency should not be neglected when studying the formation of investment syndicates.

Table 3 shows the correlations between the variables. The size of the correlations between the independent variables indicates no problems with multicollinearity. In addition, variance inflation factors were calculated for the independent variables to detect multicollinearity. The results did not indicate any problems (VIF < 3).

The results of the SEM model are presented in Table 4. Because it is recommended that centered variables be used in the SEM analysis (Williams et al. 2003), we rescaled the variables into standardized z-scores. We estimate two path models: one with the number of VC executives and one with the total size of the funds under management as proxies for VC firm size. The path coefficients of both models using normal theory maximum likelihood estimation are presented in Table 4.

The hypothesis tests conducted in the structural equation modeling context assume that the data used to test the model arise from a joint multivariate normal distribution. The dependent variable of our study (syndication frequency) is an ordinal (non-normal) variable for which we assume a normal distribution. If data are not joint multivariate normal distributed, the chi-square test statistic of overall model fit will be inflated, and the standard errors used to test the significance of individual parameter estimates will be deflated. The robust estimation approach corrects the model fit chi-square test statistic and standard errors of individual parameter estimates. This approach was introduced by Satorra and Bentler (1988) and incorporated into the EQS program. The robust approach works by adjusting downward the obtained model fit chi-square statistic based on the amount of non-normality in the sample data. The larger the multivariate kurtosis of the input data, the stronger the applied adjustment to the chi-square test statistic. Standard errors for parameter estimates are adjusted upwards in much the same manner to reduce appropriately the type 1 error rate for individual parameter estimate tests. Although the parameter estimate values themselves are the same as those from a standard ML solution, the standard errors are adjusted, with the end result being a more appropriate hypothesis test that the parameter estimate is zero in the population from which the sample was drawn. However, comparison with the ML solution did not indicate any significant changes. In addition, Mardia’s kappa test suggests no problematic kurtosis. Thus, we conclude that the non-normality of the ordinal data did not produce a problematic violation of the assumption of a joint multivariate normal distribution.

As indicated by the fit indices, both size models show a good absolute fit (GFI = 0.96) and comparative fit (CFI = 0.97–0.98; RMSEA = 0.05–0.06) with the data. The total R-square of the models is 0.16 and 0.17, respectively. The model accounts for about 16% of the variance in syndication frequency, which can be considered substantial considering the perceptual nature of the data and the raw measurement of the dependent variable in five categories. We compared the different alternative specifications in line with the procedure suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), using the Lagrange multiplier test, and found that no alternative specification of the parameters would have led to a model that better represented the data.

The path coefficients from VC Firm Size → Need for financial resources are similar and significant which supports hypothesis 1 that VC firm size is negatively related to the need to gain access to financial resources through syndicated VC investment. The path coefficient in Model II is larger and significant at a higher level. Model I provides only weak support (p < 0.10) for hypothesis 1. The path coefficients in Model I and II from VC firm size → Need for management resources are similar but the path coefficient is not significant in Model II. Our hypothesis 2 that VC firm size is negatively related to the need to gain access to management resources through syndicated VC investment is therefore only supported with respect to VC firm size as the size of the funds under management. One explanation may be that the benefits of specialization are better captured by fund size than by the number of executives in the firm. The path coefficients from VC firm size → Deal-flow reciprocation are positive and significant (p < 0.05) in Model I and Model II. The results therefore provide support for hypothesis 3 that VC firm size is positively related to the capability for deal-flow reciprocation through syndicated investment. The path coefficients from VC firm size → Adaptive coordination efficiency are negative and significant (p < 0.05) in Model I and Model II. The empirical evidence therefore provides support for hypothesis 4 that VC firm size of the focal firm is negatively related to the adaptive coordination efficiency of a syndicated investment.

The paths of all control variables are significant and in line with expectations. Large firms are more likely to have a lead role, be older, and invest in later stage deals. However, the path coefficient Size → Lead syndication is surprisingly small and only significant at the 10% level. This indicates that small VC firms also frequently act as lead in syndicated investments. Further, the direct effect of firm size is still substantial in the number of executives model. The significance of the second order term and the improved fit of the model indicate that the relationship is curvilinear. These results indicate that either fund size better captures firm size effects or that firm size effects play a role beyond the hypothesized mediating effects of resources access needs and capabilities.

5 Discussion

Our study is the first to explore simultaneous opposing mediation effects of resource access needs and resources access capabilities on firm size effects in the relationship between firm size hybrid governance. Building on arguments from the extended resource-based view (Lavie 2006), transaction costs economics (Williamson 1985), and consistent with insights from the alliance literature (e.g., Podolny 1994; Stuart 2000), we developed the argument that small firms have a higher need to gain access to external complementary resources, whereas large firms have a better capability to gain access to reciprocal deal-flow and face higher transaction costs of adaptive coordination in hybrid governance arrangements.

The empirical evidence, based on survey data from executives in the VC industry, supports our theoretical framework. We found that VC firm size has opposing effects on the resource access needs and capabilities of syndicated investment, and these factors in turn determine the level of syndication frequency.

The capability for resource access is not always positively driven by the small size of the firm. Our theoretical model, which we empirically validate, suggests that large firms have an advantage in syndication for reasons that relate to the capability to be invited to future deal-flow; however, we show that small firms also have a capability advantage in adaptive coordination of syndicated investment. This is an interesting finding and one that enables us to develop a more nuanced understanding of the trade-offs that size imposes on the capability to gain access to resources through cooperative behavior.

We attach particular importance to the role that network-based assets play in shaping the syndication needs and capabilities of different size of VC firms. Our consideration of network-based assets highlights that syndication between VC firms is not a one-off event, but likely involves repeated syndication of different investments over time. Network positions affect syndication behavior through two main mechanisms. From an RBV perspective, large firms are more motivated to syndicate for deal-flow reasons because their central network position means that they are more likely to be invited into future syndicates. Therefore, the expectation of reciprocated deal-flow is greater for large firms. From a TCE perspective, the larger a VC firm, the greater the potential network damage it may incur through syndication, and hence the greater its transaction costs when syndicating. Firms, therefore, face an important size-imposed trade-off when assessing the upside and downside of network effects in syndication. This analysis demonstrates that in order to explain a complex phenomenon such as syndication behavior, it is necessary to move beyond a single theory approach to model building. Single theory approaches may be unsuitable for studying complex phenomena (see Gray and Wood 1991). By bringing together insights from both the RBV and TCE we are able to better understand the trade-offs VC firms make when deciding on their syndication strategy.

The results of this study have important managerial implications. The need to access different resources influences the syndication behavior of VC firms, which in turn is influenced by the size of the firm. For small firms the benefits of syndication are greater for financial resources and managerial expertise resources, and they are more efficient in coordinating VC investment. However, they are less likely to be invited into future deals. Small VC firms should hence develop an explicit syndication strategy for developing resources that make them more attractive as syndicate partners. Given that small VC firms are less likely to be invited in syndicates, they need to actively build ties with other, well-respected VC firms and offer them specific advantages. They might, for example, invest heavily in alternative ways of deal-flow generation, enabling them to spot interesting proposals early and hence to invite colleagues in a valuable investment proposal, hoping their more central network position will lead to deal reciprocation in the future. Further, they might build specific resources or capabilities, e.g., industry knowledge and innovation, that makes them more attractive to syndicate partners. For example, small firms may be in a better position to create entrepreneurial rents from its available resources. Large firms may, for example, suffer from core rigidities, reduced experimentation, and lower incentive intensity (Mosakowski 2002). Particularly in innovative contexts such as early stage VC investments, such features can become critical, and large VC syndicate partners may need small VC firms for providing support in entrepreneurial processes such as product innovation and new business formation. This may especially be the case where large firms face rapidly changing technology and knowledge environments with short product life cycles that make rapid dissemination of information necessary. These specific skills and resources may help to reduce their liabilities of smallness.

The finding of a negative association between the adaptive coordination efficiency of syndication and VC firm size has practical implications in the context of the recent development of club (i.e., syndicated) deals at the larger buy-out end of the market (Cumming et al. 2007). Club deals have been undertaken to enable large deals to be consummated that would otherwise be too risky for single VCs. In addition to this risk-spreading rationale, club deals may bring together the diverse specialist skills required to restructure and regenerate a particular deal. However, coordination may be problematical when restructuring of distressed buyouts is required. Since all large funds are likely to have extensive market expertise in order to be able to raise large funds, coordination problems may be exacerbated if the executives from each syndicate partner have strong view about how restructuring should be effected. The implication is that large VC firms need to exercise considerable due diligence in selecting syndicate partners if they are to protect their network positions. This issue assumes particular importance given the recent negative criticism of the behavior of large VC firms (Treasury Select Committee 2007).

Next to further study of trade-off effects of firm size on resource access needs and resource access capabilities through syndication, future research could further validate and extend this study along several dimensions. For example, the results of this study depend on the perceptions and observations of one VC executive in a VC firm. Future research could cross-validate the perceptions of several executives within one firm in order to assess the impact of single respondent bias. A further potential limitation is that the data could be subjected to measurement context effects, which refers to any artifactual covariation produced from the context in which measures are obtained independent of the content of the construct themselves (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This bias is caused by the fact that both the predictor and criterion variable are measured at the same point in time using the same medium. To overcome the problem of common context bias, one might try to obtain the data for the predictor variable from an external source. Unfortunately, this was not possible for this study because we have no link between the names of the respondents and the response file and a recommendation for future research would be to gather data from different external sources.

Another limitation of this study is that we did not analyze longitudinal effects. Past syndication behavior may influence the future needs and capabilities to syndicate. For example, small VC firms may gain status by being associated with large reputable and well-connected firms in VC syndication. In addition, advanced screening and monitoring of small syndication partners by reputable and well-connected firms may improve the status of small VC firms in future deals. Future research could explore the long-term effects of syndicated investment on the resource access needs and capabilities of small and large VC firms. We hope that future research will use the ideas presented in this paper and develop knowledge that will help small and large firms to maximize firm value from external resources through hybrid governance arrangements.

Notes

In order to make sure that our results are not driven by a restrictive specification of the functional form, second order terms were included. However, the second order terms were insignificant and therefore removed from the analysis.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. (1977). Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 421–458.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120.

Barney, J. B. (1997). Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Bercovitz, J., & Mitchell, W. (2007). When is more better? The impact of business scale and scope on long-term business survival, while controlling for profitability. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 61–80.

Brander, J. A., Amit, R., & Antweiler, W. (2002). Venture capital syndication: Improved venture selection versus the value-added hypothesis. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 11, 423–452.

Briggs, S. R., & Cheeck, J. M. (1988). On the nature of self-monitoring: Problems with assesment, problems with validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 663–678.

Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 9–30.

Bygrave, W. D. (1987). Syndicated investments by venture capital firms: A networking perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 2, 139–154.

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. (1981). Analysing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohrnstedt & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues (pp. 65–115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Carter, R., & Hodgson, G. M. (2006). The impact of empirical tests of transaction cost economics on the debate on the nature of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 27, 461–476.

Chen, M.-J., & Hambrick, D. C. (1995). Speed, stealth, and selective attack: How small firms differ. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 453–482.

Conner, K. R. (1991). A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: Do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of Management, 17, 121–154.

Conner, K. R., & Prahalad, C. K. (1996). A resource-based theory of the firm: Knowledge versus opportunism. Organization Science, 7, 477–501.

Cumming, D. J. (2006). The determinants of venture capital portfolio size: Empirical evidence. Journal of Business, 79, 1083–1126.

Cumming, D., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2007). Private equity, leveraged buyouts and governance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13, 439–460.

Das, B. J., & Husain, J. H. (1993). Survival of small firms: An examination of the production flexibility model. International Journal of Management, 10, 283–287.

De Clerq, D., & Dimov, D. (2004). Explaining venture capital firms’ syndication behaviour: A longitudinal study. Venture Capital, 6, 243–256.

DeVellis, R. (1991). Scale development. Newbury Park, NJ: Sage Publications.

Dobrev, S. D., & Carroll, G. R. (2003). Size (and competition) among organizations: Modeling scale-based selection among automobile producers in four major countries, 1885–1981. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 541–558.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 660–679.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1996). Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science, 7, 136–150.

Forbes, D. P., & Milliken, F. J. (1999). Cognition and corporate governance: Understanding boards of directors as strategic decision-making groups. Academy of Management Review, 24, 489–505.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with observable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Gray, B., & Wood, D. J. (1991). Collaborative alliances: Moving from practice to theory. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27, 3–22.

Gulati, R., & Higgins, M. C. (2003). Which ties matter when? The contingent effects of interorganizational partnerships on IPO success. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 127–144.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49, 149–164.

Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D., et al. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Hochberg, Y. V., Ljundqvist, A., & Lu, Y. (2007). Whom you know matters: Venture capital networks and investment performance. Journal of Finance, 112, 251–301.

Hsu, D. (2004). What do entrepreneurs pay for venture capital affiliation? Journal of Finance, 59, 1805–1844.

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of partial least squares in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 195–204.

Huntsman, B., & Hoben, J. (1980). Investment in new enterprises: Some empirical observations on risk, return and market structure. Financial Management, 9, 44–51.

Jääskeläinen, M., Maula, M., & Seppä, T. (2006). Allocation of attention to portfolio companies and the performance of venture capital firms. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31, 185–205.

Kogut, B. (2000). The network as knowledge: Generative rules and the emergence of structure. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 405–425.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3, 383–397.

Laine, M., & Torstila, S. (2005). The exit rates of liquidated venture capital funds. Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance and Business Venturing, 10, 53–73.

Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. Academy of Management Review, 31, 638–658.

Lavie, D. (2007). Alliance portfolios and firm performance: A study of value creation and appropriation in the U.S. software industry. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1187–1212.

Lerner, J. (1994). The syndication of venture capital investments. Financial Management, 23, 16–27.

Lindell, M. K., & Brandt, C. J. (2000). Climate quality and climate consensus as mediators of the relationship between organizational antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 331–348.

Lockett, A., & Wright, M. (2001). The syndication of venture capital investments. OMEGA: The International Journal of Management Science, 29, 375–390.

Manigart, S., Joos, P., & De Vos, D. (1994). The performance of publicly traded European venture capital companies. Journal of Small Business Finance, 3, 111–125.

Manigart, S., Lockett, A., Wright, M., Meuleman, M., Landström, H., Bruining, J., et al. (2006). Venture capitalists’ decision to syndicate. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30, 131–155.

Mosakowski, E. (2002). Overcoming resource disadvantages in entrepreneurial firms: When less is more. In M. A. Hitt, R. D. Ireland, S. M. Camp, & D. L. Sexton (Eds.), Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset (pp. 106–126). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Murray, G. (1999). Early stage venture capital funds, scale economies and public support. Venture Capital, 1, 351–384.

Nooteboom, B., Berger, H., & Noorderhaven, G. (1997). Effects of trust and governance on relational risk. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 308–338.

Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179–191.

Podolny, J. M. (1994). Market uncertainty and the social character of economic exchange. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 458–483.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 531–544.

Sapienza, H., Manigart, S., & Vermeir, W. (1996). Venture capitalist governance and value-added in four countries. Journal of Business Venturing, 11, 439–470.

Satorra, A., & Bentler P. M. (1988). Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysis. In Proceedings of the Business and Economics Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association (Vol. 36, pp. 308–313).

Sorenson, O., & Stuart, T. E. (2001). Syndication networks and the spatial distribution of venture capital investments. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 1546–1588.

Stuart, T. E. (2000). Interorganizational alliances and the performance of firms: A study of growth and innovation rates in a high-technology industry. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 791–811.

Stuart, T. E., Hoang, H., & Hybels, R. C. (1999). Interorganizational endorsements and the performance of entrepreneurial ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 315–349.

Treasury Select Committee. (2007). Private Equity: Vol. 1 Report together with formal minutes. Tenth Report of Session 2006–07. HC567-1.

Williams, L., Edwards, J., & Vandenberg, R. (2003). Recent advances in causal modeling methods for organizational and management research. Journal of Management, 29, 903–936.

Williamson, O. E. (1967). Hierarchical control and optimum firm size. Journal of Political Economy, 75, 123–138.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets and relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1991). Comparative economic organization: The examination of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269–296.

Williamson, O. E. (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1999). Strategy research: Governance and competence perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 1087–1108.

Wright, M., & Lockett, A. (2003). The structure and management of alliances: Syndication in the venture capital industry. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 2073–2102.

Zacharakis, A. (2002). Business risk investment risk, and syndication of venture capital deals. Denver: Academy of Management Meeting.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Verwaal, E., Bruining, H., Wright, M. et al. Resources access needs and capabilities as mediators of the relationship between VC firm size and syndication. Small Bus Econ 34, 277–291 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9126-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9126-x

Keywords

- Venture capital

- Firm size

- Investment syndication

- Resource access capabilities

- Resource access needs

- Transaction cost economics

- Hybrid governance