Abstract

Background

Cardiac defects can be the presenting symptom in patients with mutations in the X-linked gene FLNA. Dysfunction of this gene is associated with cardiac abnormalities, especially in the left ventricular outflow tract, but can also cause a congenital malformation of the cerebral cortex. We noticed that some patients diagnosed at the neurogenetics clinic had first presented to a cardiologist, suggesting that earlier recognition may be possible if the diagnosis is suspected.

Methods and results

From the Erasmus MC cerebral malformations database 24 patients were identified with cerebral bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia (PNH) without other cerebral cortical malformations. In six of these patients, a pathogenic mutation in FLNA was present. In five a cardiac defect was also found in the outflow tract. Four had presented to a cardiologist before the cerebral abnormalities were diagnosed.

Conclusions

The cardiological phenotype typically consists of aortic or mitral regurgitation, coarctation of the aorta or other left-sided cardiac malformations. Most patients in this category will not have a FLNA mutation, but the presence of neurological complaints, hyperlaxity of the skin or joints and/or a family history with similar cardiac or neurological problems in a possibly X-linked pattern may alert the clinician to the possibility of a FLNA mutation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiac defects in adults are usually sporadic and rarely considered to be part of a hereditary syndrome. The presence of other congenital malformations or a positive family history should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying, possibly genetic cause [1, 2]. Combined neurological and cardiac disease is well recognized in neuromuscular disorders [3]. However, a cardiac defect can also be the presenting symptom in patients with a congenital malformation of the cerebral cortex due to mutations in the X-linked gene FLNA (OMIM 300017). Dysfunction of this gene leads to abnormalities in outflow tract development, often manifesting as a mitral or aortic valve insufficiency and a cerebral migration disorder, characterized by clusters of grey matter along the ventricles consisting of neurons that failed to migrate to the cortex during prenatal development [4]. Some mutations in FLNA can lead to craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities, including otopalatodigital (OPD) syndrome types 1 (OMIM 311300) and 2 (OMIM 304120), Melnick-Needles syndrome (MNS, OMIM 309350) and frontometaphyseal dysplasia (FMD, OMIM 305620). The filamin proteins (FLNA, FLNB and FLNC) are products of different genes and splice variants. Filamins stabilize F-actin networks in the cell and link them to cellular membranes by binding to transmembrane receptors or ion channels, thereby regulating cell morphology, membrane integrity and cell locomotion [5]. FLNA and FLNB are widely expressed, while FLNC is restricted to the striated muscle. Mutations in FLNC have been associated with myofibrillar myopathy [6]. FLNA is highly expressed in early myotubes, developing myofibrils and migratory neurons. During myofibril development FLNA is replaced by FLNB [5]. There seems to be some functional redundancy of both proteins [7]. Mutations in FLNB have only been described in skeletal chondrodysplasia, like Larsen syndrome (OMIM 150250), spondylocarpotarsal Dysostosis (OMIM 272460), atelosteogenesis I and III (OMIM 108720 and 108721) and boomerang dysplasia (OMIM 112310). Among these, only Larsen syndrome occasionally presents with cardiac outflow tract defects and none with cerebral periventricular nodular heterotopia (PNH). In this study, we evaluated patients known with a FLNA mutation for cardiac abnormalities.

Methods

We used our database of patients with malformations of cortical development to determine how often we see a combination of cerebral PNH and cardiac abnormalities due to FLNA mutations, to describe the patient characteristics and to provide information for the cardiologist as to when they should be alert to the possibility of an associated cerebral malformation. FLNA mutations were identified by direct sequencing of exons and intron exon boundaries (reference sequence NM_01110556.1).

Results

From our ongoing database of patients with malformations of cortical development, we identified 24 patients with bilateral PNH without other cerebral cortical malformations [8]. In six patients this was due to a pathogenic mutation in FLNA. Five of these FLNA patients had a cardiac defect in the outflow tract. Details of these five patients are found in the table and clinical descriptions below. Four presented to a cardiologist before the diagnosis of the cerebral abnormalities was known. In the 18 other patients with bilateral PNH without other cerebral malformations pathogenic mutations in FLNA were excluded, and none of these had a cardiac defect as evaluated by a cardiologist. Patients with other malformations of cortical development were not all screened by a cardiologist, so the incidence of cardiac defects in this group cannot be inferred from our data.

Clinical reports

Patient 1

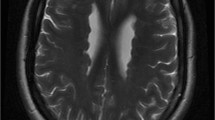

The first patient is a boy (patient 1 in Table 1 and Figs. 1, 2), the third child of healthy parents of Somalian descent. A prenatal ultrasound at 20 weeks showed an unclassified cardiac abnormality. Pregnancy and term birth (38 weeks) were uncomplicated. Birth weight was 2,635 g, head circumference 34 cm (normal). Cardiac ultrasound and catheterization showed a cardiac malformation consisting of a situs solitus, AVVA concordant, mono-atrium, mitral atresia, hypoplastic left ventricle, double outlet right ventricle, patent arterial duct, severe hypoplasia of the transverse aortic arch and coarctation of the aorta. Physical exam showed a normal abdomen, cryptorchidism, a closed palate and normal facies, apart from minor anomalies of a preauricular pit on the left side and mildly posteriorly rotated ears. Neurological evaluation in the neonatal period showed an alert infant with normal movements, reflexes and muscle tone. EEG showed no epileptiform discharges. Brain MRI showed wide cerebral ventricles with bilateral PNH, a normal cortex, and a bifid septum pellucidum, and an enlarged retrocerebellar space with normal cerebellum and brainstem. Thorax CT angiogram performed to classify the cardiac abnormality additionally showed incomplete fusion of the distal third part of the sternum. The patient died at the age of 2 months of heart failure. Autopsy was not allowed and the family was lost to follow-up.

FLNA sequencing of DNA extracted from leukocytes showed two sequence changes. The missense change c.5290G>A (p.A1764T) has been reported before in a woman with PNH and has been described as pathogenic, although there is no definitive evidence [4]. The second missense change was found in exon 20 (c.3035C>T) resulting in a serine to leucine substitution at position 1012 of the protein and has not been reported before in PNH or in the OPD-spectrum. This is a change in rod 1 (repeat 1–15) before the hinge 1 domain and is predicted to be a non-tolerated amino acid change in two different computer models. It is uncertain whether the second missense change contributes to the phenotype.

Patient 2

During the first pregnancy of a unrelated healthy Dutch couple prenatal ultrasound and prenatal MRI had shown a girl with a possibly enlarged heart and mildly enlarged cerebral ventricles (patient 2 in Table 1 and Fig. 2). Delivery at term (40.6 wks) was uncomplicated. Birthweight was 2,830 g and head circumference 37 cm (+2 SD). Postnatally, cardiac ultrasound showed a secundum atrial septal defect, coarctation of the aorta and mild aortic regurgitation. The coarctation was surgically corrected at the age of 16 days by resection and end-to-end anastomosis. She showed normal to mildly delayed cognitive development and delayed motor development with hypotonia and severe hyperlaxity. Facial features show a broad forehead, prominent orbital ridges, deep set eyes with down-slant, and a flat midface. She has never had seizures, and EEG showed no epileptiform discharges. Brain MRI showed bilateral PNH and an enlarged retrocerebellar cyst (Fig. 1). At the age of 3 months she developed dyspnoea due to congenital lobar emphysema of the right middle pulmonary lobe with bronchomalacia. She was successfully treated with a pulmonary lobectomy.

FLNA sequencing of DNA extracted from leukocytes showed a missense change c.220G>A in exon 2 (p.G74R). Family studies showed the mother, not the father, to be carrier of the same mutation. Cardiological evaluation, including ultrasound, of the mother was normal. The mother has hyperlaxity. Brain MRI of the mother showed bilateral PNH, typical of FLNA mutations. She subsequently developed epilepsy at age 27 years. This missense change was absent in leukocyte DNA of the maternal grandparents. These have no FLNA related complaints or symptoms, although brain MRI was not done. Its de novo occurrence in the family renders it very likely that c.220G>A, p.G74R is a pathogenic mutation.

Patient 3

A woman with a normal IQ and an otherwise unremarkable history underwent aortic valve replacement for severe aortic valve regurgitation at age 40 in 1975 (patient 3 in Table 1 and Fig. 2). Details on the pathology were lost. At age 55 she was diagnosed with heart failure and 1 year later she underwent heart transplantation. Macroscopic pathology showed a dilated heart and a dilated aortic root. The left ventricle shows subendocardial fibrosis. At age 60 she was diagnosed with severe venous varicosis of the legs and at age 70 an infrarenal aortic aneurysm with a 4.7 cm diameter was found and treated conservatively. She never had an epileptic seizure and showed no hyperlaxity of joints or skin. At age 71 symptoms of mild cognitive decline prompted a brain CT showing bilateral PNH as a chance finding. Eight months later she died of a subarachnoid hemorrhage from a ruptured fusiform carotid aneurysm. Family history revealed that her mother had heart problems from a young age and died from heart failure at age 69, details could not be recovered. The patient had a healthy twin brother and a sister and a healthy son. The autopsy showed severe generalized atherosclerosis with mild dilatation of the thoracic aorta and an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta of 7 cm. Brain autopsy showed symmetrical bilateral PNH, and bilateral fusiform carotid aneurysms with widespread glomeruloid microvascular changes in the cerebral cortex [9].

Direct sequence analysis of the FLNA gene in DNA extracted from leukocytes showed a pathogenic frame shift mutation c.3045del5 in exon 21.

Patient 4

A 6-year-old girl presented with a cardiac murmur and was diagnosed with a mild aortic stenosis (9 mm gradient) and regurgitation with a normal left ventricle diameter that remained stable over the years (patient 4 in Table 1 and Fig. 2). She is now 46 years old and has a normal IQ. She had a first generalized epileptic seizure at age 28. Brain CT showed bilateral PNH. Dysmorphic evaluation showed no abnormalities and no hyperlaxity. She has no children and one healthy brother.

Direct sequence analysis of FLNA in DNA extracted from leukocytes showed a pathogenic frame shift mutation c.3582delC in exon 22.

Patient 5

A girl presented shortly after birth with cyanosis during feeding and was diagnosed with a ventricular septal defect and aortic regurgitation (patient 5 in Table 1 and Fig. 2). At age 24 the ventricular septal defect was surgically corrected and she received an aortic bioprosthesis. At age 36 years she underwent a Bentall procedure. At age 40, she presented to a neurologist because of a complicated migraine attack with aphasia. A brain MRI showed bilateral PNH and an enlarged retrocerebellar space (Fig. 1). Family history revealed that her mother died suddenly at age 57 from a rupture of the aorta. The patient has one sister with mild aortic regurgitation, she has been invited for counseling. The patient has a healthy son.

Direct sequence analysis of FLNA in DNA extracted from leukocytes showed a pathogenic mutation frame shift mutation c.6635delTCAG in exon 41.

Discussion

Five out of six patients with a pathogenic mutation in FLNA from our database show a combination of cardiac disease and bilateral cerebral PNH. Four patients presented to a cardiologist before or at the time of their neurological workup. Neurological signs were absent or mild at that time and the diagnosis of bilateral PNH was made later due to epileptic seizures (case 4), hypotonia (case 2) or during the workup of non-related complaints. This suggests that the cardiologist had the first opportunity to recognize these patients. Recently also X-linked mitral valvular dystrophy without neurological signs or symptoms of epilepsy was found to be caused by mutations in FLNA, however, brain imaging was not reported [10]. The cardiological phenotype is not always this specific. FLNA knock out mice show midline skeletal defects and early male lethality due to cardiac malformations in atrioventricular septal and outflow tract development [11]. Human patients also show abnormalities in the outflow tract ranging from patent ductus arteriosus, mitral or aortic valvular abnormalities to coarctation of the aorta, and ascending aorta aneurysm [12–14]. Cerebral PNH in FLNA patients is caused by impaired migration of later born neurons due to disrupted cell adhesion and abnormal ventricular ependymal function [15]. This shows that pathways involved in cell adhesion can both affect the neuro-epithelium and vascular development. Apart from cerebral and cardiovascular developmental defects FLNA mutations can also cause connective tissue abnormalities, and autopsy studies show abnormal glomeruloid microvascular proliferations in the brain [9, 15]. A combination of PNH and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome with joint hyperlaxity and aorta aneurysms caused by a mutation in FLNA has been described in females [16]. Neurological phenotypes associated with PNH are diverse and range from epilepsy and normal development to patients with multiple congenital anomalies and mental retardation. In males mutations are often prenatal lethal. Less severe mutations with residual filamin A function are found in males with PNH. One male patient has been described with PNH and a lethal complex cardiac malformation, including atrial and ventricular septal defect and persistent left superior caval vein [12]. Interestingly, gain of function mutations of FLNA are associated with syndromes with craniofacial and skeletal abnormalities, including otopalatodigital syndrome types 1 and 2, Melnick-Needles syndrome (MNS) and frontometaphyseal dysplasia [17]. In these syndromes several male patients have been described with heart defects, cryptorchidism and umbilical hernia, but no PNH [17]. The combination of mitral and/or aortic regurgitation and skeletal abnormalities with hyperlaxity is also found in autosomal dominant Marfan syndrome (OMIM 154700), in the allelic Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome (OMIM 182212) and in Loeys-Dietz syndrome type 1A and B (OMIM 609192 and 610168). Some neuromuscular abnormalities are described in these patients, but no cerebral cortical developmental abnormalities.

Although we did not find any cases, cardiac defects are reported to be associated with some other cerebral PNH phenotypes. Patients with Williams syndrome, caused by a microdeletion of chromosome 7q11.22-23, have distinctive facial dysmorphias, ‘elfin face’, and often cardiac defects, such as supravalvular aortic stenosis, mitral or pulmonary valve abnormalities, and atrial or ventricular septum defect. One case has been described with associated PNH [18]. In chromosome 6q terminal deletion syndrome, brain MRI commonly shows hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, and a few patients have been described with associated PNH [19]. About half of 6q terminal deletion patients are reported to have cardiac abnormalities, primarily ventricular or atrial septum defect. Distal duplications of chromosome 5p have been associated with PNH in two patients, one of which also had atrial septum defect and mitral and tricuspid valve prolapse [20]. Genetic factors related to similar cardiac malformations without PNH are being widely investigated, but still only few genes are known to cause a developmental defect of the atrioventricular septum and the outflow tract in humans [21–23].

Conclusion

Patients with mutations in FLNA show a cardiological phenotype with aortic or mitral regurgitation, coarctation of the aorta or other left-sided malformations. Although patients with cardiac defects in this category are numerous and most will not have a FLNA mutation, the presence of neurological complaints, hyperlaxity of the skin or joints and/or a family history with similar cardiac or neurological problems in a possibly X-linked pattern should alert the clinician to the possibility of a FLNA mutation. Recognition will enable genetic testing and genetic counseling for patients and their family.

References

König K, Will JC, Berger F, Müller D, Benson DW (2006) Familial congenital heart disease, progressive atrioventricular block and the cardiac homeobox transcription factor gene NKX2.5: identification of a novel mutation. Clin Res Cardiol 95(9):499–503

Posch MG, Perrot A, Berger F, Ozcelik C (2010) Molecular genetics of congenital atrial septal defects. Clin Res Cardiol 99(3):137–147

Lauschke J, Maisch B (2009) Athlete’s heart or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? Clin Res Cardiol 98(2):80–88

Sheen VL, Dixon PH, Fox JW, Hong SE, Kinton L, Sisodiya SM, Duncan JS, Dubeau F, Scheffer IE, Schachter SC, Wilner A, Henchy R, Crino P, Kamuro K, DiMario F, Berg M, Kuzniecky R, Cole AJ, Bromfield E, Biber M, Schomer D, Wheless J, Silver K, Mochida GH, Berkovic SF, Andermann F, Andermann E, Dobyns WB, Wood NW, Walsh CA (2001) Mutations in the X-linked filamin 1 gene cause periventricular nodular heterotopia in males as well as in females. Hum Mol Genet 10(17):1775–1783

Zhou AX, Hartwig JH, Akyürek LM (2010) Filamins in cell signaling, transcription and organ development. Trends Cell Biol 20(2):113–123

Kley RA, Hellenbroich Y, van der Ven PF, Fürst DO, Huebner A, Bruchertseifer V, Peters SA, Heyer CM, Kirschner J, Schröder R, Fischer D, Müller K, Tolksdorf K, Eger K, Germing A, Brodherr T, Reum C, Walter MC, Lochmüller H, Ketelsen UP, Vorgerd M (2007) Clinical and morphological phenotype of the filamin myopathy: a study of 31 German patients. Brain 130(Pt 12):3250–3264

Sheen VL, Feng Y, Graham D, Takafuta T, Shapiro SS, Walsh CA (2002) Filamin A and Filamin B are co-expressed within neurons during periods of neuronal migration and can physically interact. Hum Mol Genet 11(23):2845–2854

de Wit MC, Lequin MH, de Coo IF, Brusse E, Halley DJ, van de Graaf R, Schot R, Verheijen FW, Mancini GM (2008) Cortical brain malformations: effect of clinical, neuroradiological, and modern genetic classification. Arch Neurol 65(3):358–366

de Wit MC, Kros JM, Halley DJ, de Coo IF, Verdijk R, Jacobs BC, Mancini GM (2009) Filamin A mutation, a common cause for periventricular heterotopia, aneurysms and cardiac defects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80(4):426–428

Kyndt F, Gueffet JP, Probst V, Jaafar P, Legendre A, Le Bouffant F, Toquet C, Roy E, McGregor L, Lynch SA, Newbury-Ecob R, Tran V, Young I, Trochu JN, Le Marec H, Schott JJ (2007) Mutations in the gene encoding filamin A as a cause for familial cardiac valvular dystrophy. Circulation 115(1):40–49

Hart AW, Morgan JE, Schneider J, West K, McKie L, Bhattacharya S, Jackson IJ, Cross SH (2006) Cardiac malformations and midline skeletal defects in mice lacking filamin A. Hum Mol Genet 15(16):2457–2467

Guerrini R, Mei D, Sisodiya S, Sicca F, Harding B, Takahashi Y, Dorn T, Yoshida A, Campistol J, Krämer G, Moro F, Dobyns WB, Parrini E (2004) Germline and mosaic mutations of FLN1 in men with periventricular heterotopia. Neurology 63(1):51–56

Fox JW, Lamperti ED, Ekşioğlu YZ, Hong SE, Feng Y, Graham DA, Scheffer IE, Dobyns WB, Hirsch BA, Radtke RA, Berkovic SF, Huttenlocher PR, Walsh CA (1998) Mutations in filamin 1 prevent migration of cerebral cortical neurons in human periventricular heterotopia. Neuron 21(6):1315–1325

Solé G, Coupry I, Rooryck C, Guérineau E, Martins F, Devés S, Hubert C, Souakri N, Boute O, Marchal C, Faivre L, Landré E, Debruxelles S, Dieux-Coeslier A, Boulay C, Chassagnon S, Michel V, Routon MC, Toutain A, Philip N, Lacombe D, Villard L, Arveiler B, Goizet C (2009) Bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia in France: frequency of mutations in FLNA, phenotypic heterogeneity and spectrum of mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80(12):1394–1398

Ferland RJ, Batiz LF, Neal J, Lian G, Bundock E, Lu J, Hsiao YC, Diamond R, Mei D, Banham AH, Brown PJ, Vanderburg CR, Joseph J, Hecht JL, Folkerth R, Guerrini R, Walsh CA, Rodriguez EM, Sheen VL (2009) Disruption of neural progenitors along the ventricular and subventricular zones in periventricular heterotopia. Hum Mol Genet 18(3):497–516

Sheen VL, Jansen A, Chen MH, Parrini E, Morgan T, Ravenscroft R, Ganesh V, Underwood T, Wiley J, Leventer R, Vaid RR, Ruiz DE, Hutchins GM, Menasha J, Willner J, Geng Y, Gripp KW, Nicholson L, Berry-Kravis E, Bodell A, Apse K, Hill RS, Dubeau F, Andermann F, Barkovich J, Andermann E, Shugart YY, Thomas P, Viri M, Veggiotti P, Robertson S, Guerrini R, Walsh CA (2005) Filamin A mutations cause periventricular heterotopia with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Neurology 64(2):254–262

Robertson SP, Jenkins ZA, Morgan T, Adès L, Aftimos S, Boute O, Fiskerstrand T, Garcia-Miñaur S, Grix A, Green A, Der Kaloustian V, Lewkonia R, McInnes B, van Haelst MM, Mancini G, Illés T, Mortier G, Newbury-Ecob R, Nicholson L, Scott CI, Ochman K, Brozek I, Shears DJ, Superti-Furga A, Suri M, Whiteford M, Wilkie AO, Krakow D (2006) Frontometaphyseal dysplasia: mutations in FLNA and phenotypic diversity. Am J Med Genet A 140(16):1726–1736

Ferland RJ, Gaitanis JN, Apse K, Tantravahi U, Walsh CA, Sheen VL (2006) Periventricular nodular heterotopia and Williams syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 140(12):1305–1311

Bertini V, De Vito G, Costa R, Simi P, Valetto A (2006) Isolated 6q terminal deletions: an emerging new syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 140(1):74–81

Sheen VL, Wheless JW, Bodell A, Braverman E, Cotter PD, Rauen KA, Glenn O, Weisiger K, Packman S, Walsh CA, Sherr EH (2003) Periventricular heterotopia associated with chromosome 5p anomalies. Neurology 60(6):1033–1036

Wessels MW, Berger RM, Frohn-Mulder IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Hoogeboom JJ, Mancini GM, Bartelings MM, Krijger R, Wladimiroff JW, Niermeijer MF, Grossfeld P, Willems PJ (2005) Autosomal dominant inheritance of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Am J Med Genet A 134A(2):171–179

McBride KL, Pignatelli R, Lewin M, Ho T, Fernbach S, Menesses A, Lam W, Leal SM, Kaplan N, Schliekelman P, Towbin JA, Belmont JW (2005) Inheritance analysis of congenital left ventricular outflow tract obstruction malformations: segregation, multiplex relative risk, and heritability. Am J Med Genet A 134A(2):180–186

Elliott DA, Kirk EP, Yeoh T, Chandar S, McKenzie F, Taylor P, Grossfeld P, Fatkin D, Jones O, Hayes P, Feneley M, Harvey RP (2003) Cardiac homeobox gene NKX2–5 mutations and congenital heart disease: associations with atrial septal defect and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 41(11):2072–2076

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Erasmus MC grant 2008 to IdC and GM.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Wit, M.C.Y., de Coo, I.F.M., Lequin, M.H. et al. Combined cardiological and neurological abnormalities due to filamin A gene mutation. Clin Res Cardiol 100, 45–50 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0206-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0206-y