Abstract

In this paper we investigate differences between the organizational values of ministries and semi-autonomous executive agencies (quangos) that operate at arms’ length. Quangos are expected to operate more business-like, hence they can be expected to value profitability and other NPM-related values higher than ministries. Value incongruence between quangos and ministries is hypothesized to decrease their level of trust. These hypotheses are tested, using combined data from two Dutch surveys (n = 324). The results confirm the expectations, although different types of quangos have different degrees of value (in)congruence, which may lead to variations in the quality of the relationship with their parent ministry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most studies into organizational values contrast the public and private domain, but do not investigate differences within the public sector (van der Wal & van Hout, 2009). It is, however, questionable to presuppose that values will be shared throughout the entire public sector, which consists of many different levels and organizational structures. Indeed, there is some evidence of differences between the value preferences of core public organizations such as federal ministries on the one hand and parapublic organizations such as hospitals and schools on the other (e.g., Lyons et al. 2006).

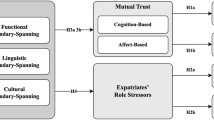

This study aims to investigate value congruence within the public domain. We will focus our analysis on the relationship between core government organizations (i.e., ministries) and so-called quangos; semi-autonomous bodies that operate at arm’s length of the government, carrying out a variety of executive and/or regulatory public tasks (Greve et al. 1999). Investigating value congruence between ministries and their quangos is highly relevant for two reasons.

First, the number of quangos has increased strongly as a result of the rise of New Public Management (Pollitt & Talbot, 2004; Christensen & Laegreid, 2003; OECD, 2002). In line with the NPM philosophy, quangos were designed on the basis of specific values, such as efficiency, economy and effectiveness because it was believed that executing policy on the basis of such business-like values could not be realized within the traditional government bureaucracy. In theoretical terms, business-like or NPM values are therefore expected to be valued higher in quangos than in ministries (van der Wal, de Graaf & Lasthuizen 2008; Maesschalk, 2004; James, 2001; Hood 1991, 1995). We will test this expected difference.

Second, the rise of quangos has led to a series of new questions about governance and steering by their political and administrative principals (e.g., Rommel & Christiaens, 2009; Christensen & Laegreid, 2006; van Thiel, 2006; Pollitt, 2005; Pollitt et al. 2004; James, 2003; Veenswijk & Hakvoort, 2002; Kickert, 2001; 2004). This is also known as the delegation or principal-agent problem; ministries cannot always be certain (or trust) that quangos will perform in accordance with the contract. Therefore, ministries will try to steer or control quangos. Pollitt’s (2005) review of the literature on this topic shows that there are many factors that influence how (well) ministries can steer quangos, ranging from functional characteristics (size of the organization in budget and personnel), the type of task (e.g. the required expertise and observability of outputs), political saliency, and the previous behaviour or relationship between quangos and agencies (‘cultural’ factors in Pollit’s words). The capacity of a ministry to steer an agency is highly contingent on these different factors but we know very little about how this works. Recent evaluation studies report incidents of conflict and distrust, and deficits in the steering capacity of parent ministries (e.g., Rommel & Christiaens, 2009; van Thiel & Pollitt, 2007; ‘t Hart & Wille, 2006; Boyne et al., 2003). A problematic relationship between quangos and ministries, can affect both the effectiveness of policy implementation as well as the possibilities for ministerial accountability. We will argue below why value congruence could contribute to a good, trusting relationship between quangos and (parent) ministries, and test this claim in the remainder of this article. If found to be true, value congruence could be used to improve the steering capacity of ministries.

The main research questions are therefore: What is the degree of congruence between the organizational values of ministries and quangos in the Netherlands, and what is the effect of value congruence on the trust between ministries and quangos? First, an overview is presented of the current public administration debate on values. Then hypotheses will be generated with regard to value congruence and its relationship with trust. After describing the methodology and samples that were used—the data for this study come from two separate surveys that were conducted in the Netherlands—the results of our analysis will be presented. We conclude with a discussion of the results and by presenting a number of issues that merit attention in future research.

Different value orientations within the public sector

There is a steadily growing body of empirical research on the ethics and values of public sector organizations and employees in the US and Canada (e.g., Bowman and Connolly Knox, Bowman and Knox, 2008; Goss, 2003; Kernaghan, 2003; Kim, 2001), as well as in different countries in Europe (e.g., Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007; van den Heuvel et al. 2002; van der Wal & Huberts, 2008; Vrangbaek, 2009). What has fueled the recent wave of publications on public values is the assumed influence of businesslike or managerial approaches to government, such as New Public Management (NPM; Hood 1991), and management by measurement (Noordegraaf and Abma, 2003) on traditional public sector values such as ‘impartiality,’ ‘lawfulness,’ and ‘neutrality’ (e.g., Eikenberry and Kluwer 2004; Frederickson, 2005; Kernaghan, 2000, 2003; Lane 2000).

Public management reforms in a majority of OECD countries during the last two decades have infused doubts, concerns and confusion about the state of public service values in those countries (Van Wart 1998; Kernaghan 2000, 2003), and about the ability to safeguard classical public values amidst the wave of privatization and liberalization in the last two decades (Beck Jørgensen & Bozeman 2002; De Bruijn & Dicke, 2006). Or, as Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007:357) conclude in their review study on public values: “In particular, much of the literature praises recent reforms such as New Public Management and Reinventing Government. However, there is an emerging literature that, as a reaction, praises the old virtues of classic administration or, alternatively, launches new progressive models such as “new public governance” or “new public service”.” Such sets of values often include values with a more general public or social character (humaneness, social justice), or in the typology of Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007: 360–361) refer to “transformation of interests to decisions” and “relationship to public administration and the citizens,” while others (‘expertise,’ ‘efficiency’) are specific professional and organizational values, or, values referring to “behavior of public-sector employees” and “intra-organizational aspects of public administration” (ibid. 361).

Research findings on the actual rise of NPM values in the public domain are however scarce and contradictory. For example, Posner and Schmidt (1984: 448) discovered that government managers consider values like effectiveness, efficiency, reputation and service to the public equally important, in a survey that was conducted before the beginning of the NPM-era! Similarly, a Danish survey shows that next to more traditional public service values, ‘innovation’ and ‘renewal’ are considered most important (Beck Jørgensen, 2006; Vrangbaek, 2009). On the other hand, van der Wal et al. (2008) show a fairly traditional and consistent value pattern, in this case for the Netherlands. The most important public sector values, (‘accountability,’ ‘lawfulness,’ ‘incorruptibility,’ ‘expertise,’ ‘effectiveness,’ ‘impartiality,’ and ‘efficiency’) are consistent with often-mentioned crucial public sector values in administrative ethics literature (e.g. Kaptein & Wempe, 2002: 237–46; Kernaghan, 2003: 712), both in earlier research among Dutch civil servants (van den Heuvel et al., 2002) and in Dutch public sector codes of conduct (Ethicon, 2003).

Not only do different empirical studies show different sets of public values, it is in itself not undisputed which values belong to which sector and organization, and why. For example, within the NPM debate, values are classified as ‘old’ or ‘traditional,’ on the one hand, and ‘new’ or ‘emerging,’ on the other (e.g., Lane and Bachmann, 1996; Kernaghan 2003). Thus, van den Heuvel et al. (2002) conclude in their empirical study on public sector values that ‘efficiency’ is an NPM value (as opposed to values characterized as Weberian), while Weber’s ideal bureaucracy specifically “stresses the importance of functional specialization for efficiency” (Rosenbloom, 1983: 447). Nevertheless, in most studies and scholarly writings the increased emphasis on the efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery is considered to be part of a more business-like philosophy (e.g., Lane and Bachmann, 1996; Frederickson 2005).

Evidence on differences in value orientations between core government organizations and quangos—organizations that function at arm’s length of the public sector core—is even more limited and less consistent than evidence on public values in general. A small number of studies as well as common government discourse during the last two decades seem to indicate that quangos are designed on the basis of specific values, such as ‘efficiency,’ ‘economy,’ and ‘effectiveness,’ because it is believed that executing policy on the basis of such business-like values cannot be realized within the traditional government bureaucracy (e.g., Christensen & Laegreid, 2003; Pollitt & Talbot, 2004; van Thiel, 2004; Hood, 1991). More specifically, a recent study by Lyons et al. (2006) shows work value differences between employees from core public and parapublic organizations, especially for the health care and educational sector. Findings of van der Wal (2008) also indicate that managers from executive agencies and parapublic organizations attribute more importance to businesslike values, and portray a strong desire to operate even more businesslike in the near future. Finally, de Bruijn and Dicke (2006) and Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2002) indicate that market-like values may be appreciated at the expense of classical public values in parts of the public sector that have been autonomized, liberalized or privatized.

It therefore appears to follow that the following business-like or NPM values would be expected to be valued higher in quangos than in their parent ministries (van der Wal & Huberts, 2008; Maesschalk 2004; Hood 1991, 1995):

- H1 :

-

In quangos ‘business-like’ values, such as ‘efficiency,’ ‘effectiveness,’ ‘innovativeness,’ ‘profitability’, ‘serviceability’ and ‘sustainability’ will be rated higher than in parent ministries

Shared values, trust and the relationship between ministries and quangos

In the Dutch political system,Footnote 1 the management and control of quangos is carried out by ‘parent ministries’ i.e. the ministry in charge of the policy sector in which a quango operates (Yesilkagit & van Thiel, 2008; ‘t Hart & Wille, 2006; Kickert, 2001). There is no direct communication between parliament and quango because (individual) ministerial accountability is dominant; a quango is accountable to the minister, and the minister is accountable to parliament.Footnote 2 As a result, the most important relationship is that between a quango and its parent ministry (Yesilkagit & van Thiel 2008, cf. also Rommel & Christiaens, 2009; Pollitt 2005).

Shared values, i.e., value congruence, are pivotal to a trusting relationship, both within organizations (between employees) as well as between organizations (Reed, 2001; Lane and Bachmann, 1996). We posit that this can also apply to the relationship between ministries and quangos (Yesilkagit & van Thiel 2008; Rommel & Christaens 2009).

Trust is generally defined as having expectations about the behavior of others, and the willingness to behave according to those expectations without having any guarantee that the other party will indeed act as expected (‘risktaking’). Trust reduces the uncertainty of the principal (ministry) about the agent’s (quango) performance; it reduces transaction costs and lubricates relations and cooperation; it leads to obedience, compliance and commitment; and it increases the motivation and performance of employees and organizations (Edelenbos & Klijn, 2007; Koivumaki and Mamia 2006; Nooteboom, 2002; Kramer, 1999; Davis et al. 1997). Because of all these benefits, a trusting relationship will facilitate ministerial accountability and improve the relationship between ministries and quangos (van Thiel & Yesilkagit, 2007).

Trust is also a reciprocal matter; giving trust is rewarded with trust, giving distrust is sanctioned with distrust (Koivumaki & Mamia, 2006; Langfred, 2004; Kramer, 1999). Trust is built up over time, and through interactions between actors (individuals and organizations). It is one of the few commodities whose value increases with use (Dasgupta, 1998). Because of its reciprocity, value congruence (‘sharing’) is expected to increase trust between quangos and ministries:

- H2 :

-

The higher the degree of organizational value congruence between parent ministries and quangos, the higher quangos will rate the level of trust between themselves and the ministries

Or, alternatively, value incongruence is expected to lead to lower levels of trust (as we will use value incongruence in our analyses, it is important to state this expectation explicitly here).

Methodology

To be able to compare the public values of ministries and their quangos, we have merged two data sets: one containing data predominantly from parent ministries (and some quangos), and one from quangos only. Operationalizations from the first data set were used as the basis for comparison between quangos and ministries; data from the second set were matched as much as possible. All data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0.

Data set 1

The first data set is the result of a survey among 231 top officials of the Dutch federal government (sample of 778 members of the Senior Civil Service; response rate of 30 percent). Almost 65 percent of the respondents are working in a ministry; the other 35 percent in a quango, in particular executive agencies (see the explanation of quango types later in this section). With regard to gender and age, the sample closely resembled the population (van der Wal, 2008).

Respondents were asked to rate how important certain values were in organizational decision-making, on a scale from 1 (least important) to 10 (most important). Because the objective was to paint a broad picture of the prominence of all 20 values, the rating method seemed the most suitable instrument. Advocates of rating state that in actual decision-making situations, agents attribute equal importance to several different values at once without being aware of possible conflicts between those values (cf. Hitlin & Pavilian, 2004; Schwartz, 1999). Making such conflicts transparent is an interesting element of the rating method. Rating is also easier to analyze (statistically) than ranking. It was explicitly stated that the respondents were supposed to rate those values that were considered “most important when decisions are being made within the unit or organization that you supervise,” emphasizing values that guide organizational decision making rather than managers’ individual moral opinions. By doing this, consideration of actual daily decision-making behavior was emphasized. The total set of 20 values that was listed in the survey was derived through a content analysis (Krippendorf, 1981) of recent Public Administration literature (see van der Wal et al., 2006). Each value was given a clear definition to reduce the effect of individual respondent perceptions and interpretations (shown in Table 2).

Data set 2

The second data set resulted from a survey among officials of 219 Dutch public sector organizations. From this dataset we have selected the respondents from the two best known types of quango (see below); executive agencies (n = 16, response rate 44%) and ZBOs (n = 84, response rate 43%). The samples proved to be representative for the different types of quangos, policy sectors and tasks (van Thiel & Yesilkagit 2006). The questionnaire consisted of 50 questions on different topics, regarding for example the financial system in use, audit and accountability, organizational culture, influence on the development of new policies, position and role of the board, and the use of a large number of management techniques like performance indicators, HRM and quality care.Footnote 3 All questions relate to characteristics of the organization; respondents were not asked for individual opinions but to answer the questionnaire on behalf of the organization—just like in the first survey. In most cases (69 percent), the questionnaire was answered by either the director (46 percent) or secretary of the board (23 percent).

Types of quangos that participated

There are many different types of organizations that can be labeled quango. Each country has its own types, forms and labels (see e.g., Greve et al., 1999; Pollitt et al., 2004; Allix & Van Thiel, 2005). For this study, we have selected the two best-known types of Dutch quangos: executive agencies and ZBOs.

Executive agencies (in Dutch: agentschappen) have no legal personality and all their decisions are subject to full ministerial accountability. They are former directorates of ministries. Their autonomy is restricted to managerial decisions, within legal and financial boundaries. The executive agency model became popular in The Netherlands from 1994 on, and is coordinated by the Ministry of Finance (for more information see van Thiel & Pollitt, 2007; Pollitt et al., 2004).

ZBOs are independent administrative bodies (in Dutch: zelfstandige bestuursorganen). They have more autonomy than executive agencies. Almost all ZBOs have legal personality (with about about 60% based on public and 40% on private law). ZBO performance is only in part subject to ministerial accountability (see footnote 2). Performance agreements are laid down in annual contracts or other documents (van Thiel, 2001).

Joint data set

The joint set contains data from 324 respondents, almost equally divided between ministries (45 percent, n = 145) on the one hand, and between the two types of quangos on the other hand (executive agencies 29% [n = 94] and ZBOs 26% [n = 85]) Table 1 shows the distribution of respondents.

All thirteen Dutch ministries are present in the joint data set. 27 executive agencies are present, out of the 40 agencies that currently exist in The Netherlands. 84 ZBOs are included in the joint data set, out of the 195 organizations that were invited to participate in the second survey. However, some ZBOs belong to the same cluster, such as the police authorities (9 ZBOs in the sample), the chambers of commerce (10) and the commissions for land attribution (2). A cluster of ZBOs shares the same legal basis, but each organization is a separate entity. Hence they will not be considered as one and the same quango, as they may rate values differently depending on local circumstances.

The number of respondents varies per type of organization; for ministries the range is between 1 and 16 respondents, for executive agencies between 1 and 22 respondents, and for ZBOs between 1 and 2. We have taken several precautions to ensure that the different numbers of respondents per organization did not lead to problems for our analyses. For example, we have checked the variance in value ratings between respondents from the same organization (ministry or quango). There were no (statistically) significant deviant scores; hence we use the mean ratings as representative for the organization.

Organizational values

Value definitions from the first survey were used as the basis for comparison. To match these, questions were used from the second survey with regard to:

-

The culture of the organization (“how typical is this characteristic for your organization,” recoded from a scale 1–7 to 1–10);

-

The use of management techniques, originally measured on a 3 point scale (seldom, often, frequent) and recoded to 1–10 (by multiplication);

-

Self-assessment of the performance of the organization (on a scale 1–10); and

-

Frequencies of interactions with the parent ministry and third parties (on different scales, all recoded to 1–10).

Table 2 shows the measurements that were selected for the comparison. For some organizational values, equivalents were readily available (see e.g., ‘honesty,’ ‘integrity,’ and ‘dedication’). For others, variables were merged (see e.g., ‘lawfulness,’ ‘collegiality,’ and ‘serviceability’) or a negative indicator had to be recoded (e.g., ‘impartiality’ and ‘obedience’). These operationalizations are based on the assumption that if a particular characteristic is considered important, it will be reflected in the organizational conduct. For example, the use of a management technique like benchmarking is an indication of the organization’s willingness to account for its performance and learn how to improve (‘accountability’). Only in one case were we unable to find a matching measurement. Because this concerned a value (‘social justice’) that was not considered very important by respondents in the first survey we decided to use only the data from dataset 1 (i.e., for that specific value, missing data for organizations is included only in data set 2).

To test that the operationalizations we used from the second dataset were indeed comparable to the measurements from the first data set, we used the partial overlap in respondents (see Table 1) to check for significant differences in ratings. We used t-testing in sub-samples (per organization with more than 5 respondents) and encountered no statistically significant differences (i.e., respondents from the same organization in data set 1 and 2 rate the same value orientations on average). Therefore, we assume that the operationalizations are indeed matching and can be used for comparison.

Trust

For the operationalization of ‘level of trust’ we use a question from the second data set. Quangos were asked to rate the level of trust between their organization and the parent ministry on a scale from 1 (least) to 10 (most). Note that this question was posed only to quangos, and not to parent ministries.

This is admittedly a rather crude measure of a subtle concept such as trust. Trust is contingent upon interpersonal relationships. Respondents’ perceptions may therefore have affected their answer—even though they were asked not to give their personal opinions in the survey and answer on behalf of the organization. Moreover, trust may change over time as ministries and quangos are served by new officials. More (qualitative) research would be necessary to get more in-depth information, but that could not be done within the time and resource constraints of the original two surveys. Moreover, we would like to stress the innovative nature of our study; the merger of our two databases provides a unique opportunity to study differences in value orientations within the public sector. Therefore, taking into account the aforementioned constraints, we will use the respondents’ answer to the question about trust.

Control variables

Two control variables were included: (1) the number of ZBOs operating for the same parent ministry and (2) the age of the quango. Both variables are related to interactions, a condition that helps to build trust (Koivumaki & Mamia, 2006; Nooteboom, 2002; Kramer, 1999; Dasgupta, 1998). As quangos age they may have had more time to build up a relation with the parent ministry, and hence have more trust. However, as ZBOs have more (formal) autonomy they might have less frequent interactions and therefore less trust (Yesilkagit and van Thiel, 2008). Therefore we have decided to include the number of ZBOs subordinate to the same ministry as well.Footnote 4

Results and discussion

Differences in value ratings

Table 3 shows the rankings of organizational values by Dutch ministries and quangos.

Clearly, no differences of opinion existed with regard to the top 3 of the most important values: ‘incorruptibility,’ ‘accountability,’ and ‘honesty’ (albeit in slightly different orders). However, there are important and statistically significant differences regarding nine values (based on ANOVA). ‘Transparency,’ ‘impartiality,’ ‘expertise,’ and ‘obedience’ are rated higher by ministries than quangos. Particularly with regard to ‘impartiality’ the difference is striking; ministries list it as the 7th most important value, while quangos list it at a 16th position. ‘Obedience’ is also considered more important to ministries, but was placed at the bottom of the list by both parties.

As expected, ‘profitability,’ ‘effectiveness,’ ‘innovativeness,’ serviceability,’ and ‘sustainability’ are all rated higher by quangos—in particular ZBOs—than ministries. This would confirm hypothesis 1. However, there is one important exception: the value of ‘efficiency’ is not rated higher by quangos; in fact it is the opposite. And while both types of organizations do not rate this value as very important, this finding is somewhat puzzling. Two alternative explanations come to mind—but warrant further investigation. First, the definition of ‘efficiency’ as ‘act to achieve result with minimal means’ may refer more to bureaucratic efficiency rather than the business-like operating by decreasing cost-prices and inefficiency. Such a difference in interpretation might explain the difference in preferences for this value. Second, ministries and quangos may differ in the number of other values they rank higher than ‘efficiency’. Quangos rate ‘serviceability,’ ‘collegiality,’ and ‘sustainability’ higher than ‘efficiency’ while ministries prefer ‘transparency,’ ‘impartiality,’ and ‘expertise’ to ‘efficiency’. Such a difference in rating could imply that ministries and quangos make different trade-offs between (important) organizational values.

Table 4 summarizes the main differences between value ratings. It should be noted that executive agencies differ much less from ministries than ZBOs do. Most of the statistically significant differences between quangos and ministries are in fact differences between ministries and ZBOs. This result could be explained by the fact that executive agencies are always former ministerial units, while ZBOs have different origins, including a private law basis. Moreover, ZBOs have more formal autonomy and operate at greater arms’ length. We will return to this explanation later on.

A factor analysis was applied to find out whether certain groups of values could be identified. The question of whether specific values coincide and appear together or are contradictory or even conflicting, and thus whether certain clusters or systems of values can be distinguished, is often addressed in the literature. Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007: 370) talk in this context about nodal values, values with a large number of related values, and neighbor values (370); values that are in close proximity to one another and related in meaning but certainly not synonymous. The problem, however, with distinctions such as that of Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007) is that they are often arbitrary and rather randomly configured. For instance, to empirically determine whether a value is a nodal or a neighbor value, one would need to apply advanced network analyses, and that has not been done so far.

We have replicated a factor analysis which was already applied to the data from the first data set (see van der Wal, 2008). Four factors were discerned, shown in Table 5: the ethical responsible dimension, (‘accountability,’ ‘honesty,’ ‘impartiality,’ ‘incorruptibility,’ ‘reliability’ and ‘transparency’), the HRM work ethos dimension, (‘collegiality,’ ‘dedication’ and ‘self-fulfillment’), the businesslike-managerial dimension, (‘effectiveness,’ ‘efficiency,’ ‘innovativeness,’ ‘profitability’ and ‘sustainability’), and the justice/loyalty dimension (‘obedience’ and ‘social justice’) (van der Wal, 2008: 72).

The factor analysis confirms the coherence between the business-like or managerial variables, as this is the ‘strongest’ factor. Moreover, quangos and ministries rate statistically significantly different on this factor (see Table 4). This result offers more support in favor of hypothesis 1. Furthermore, there are significant differences regarding factor 1 (ethical responsibility), which consists mainly of values that are appreciated more by ministries (cf. Table 4). The results suggest that a factorial design could be useful to compare, or contrast, those values that are rated most differently by ministries on the one hand and quangos on the other.

However, overall the coherence within the factors and the discriminatory power between them is moderate; respondents seem to rate almost all values as important (confirmed by correlations, overall factor and scale analyses on all 20 values, for example: Cronbach’s alpha 0.86, F 176.897, p < .001). This can in part be attributed to the way in which the values have been selected; based on an extensive content analysis of recent administrative literature, the 20 most important values already were selected out of a total number of more than 500 (see van der Wal et al., 2006). Therefore, we will continue our analyses with all twenty variables rather than with the four factors.

Value (in)congruence

As we expect value (in)congruence to be of influence on the level of trust between quangos and ministries (hypothesis 2), we now move to the level of specific ministries. Because of their low numbers of quangos, the ministries of Defense, Foreign Affairs, and General Affairs (the Cabinet of the Prime Minister) are excluded from the analysis. Table 6 shows on how many and for which values ratings differ statistically between the ministry and its quangos (non-significant ratings are not listed).

Differences in value ratings are indicative of value incongruence: the more statistically significant different ratings, the higher the incongruence. The Ministries of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Economic Affairs, and Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment have the highest degrees of value incongruence with their respective quangos; they have statistically different ratings on four or five different values. The Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment is the only parent ministry that shows full value congruence with its quangos.

When we further examined which values show incongruence, we discovered that in the case of the Ministries of the Interior, Housing, and Agriculture incongruence is caused by values that are considered more important by the ministries (‘impartiality’, ‘obedience’, ‘expertise’, ‘efficiency’ and ‘transparency’). The incongruence for the ministries of Finance, Education, and Health concerned values that are considered more important by quangos (‘sustainability’, ‘responsibility’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘profitability’ and ‘serviceability’). The Ministry of Economics shows a tie between values rated higher by the ministry or its quangos. Overall, the incongruence of values which were rated higher by quangos, turns out to be more frequent than the incongruence of values that were rated higher by ministries.

Interestingly, the findings in Table 4 and 6 do not entirely show the same patterns of incongruence. For example, ‘collegiality’ was considered more important by quangos than parent ministries but this difference is not replicated when looking at separate ministries. Another difference in the findings concerns two values (‘responsiveness’ and ‘effectiveness’), which are considered more important by quangos than ministries, but only between some quangos and their ministries. Such specific differences could be pivotal to the quality of the relationship between specific ministries and their quangos. Interpretation of such patterns falls outside the scope of this paper but some tentative ideas can be offered. For example, in the Dutch health sector quangos are usually based on private law, operating in an internal market that increasingly is becoming subject to commerce (van Hout, 2007). Hence, in that specific sector values like ‘profitability’ will be important, as well as (internal and external) quality assessment (‘accountability’). In the Dutch education sector, the constitutionally based freedom of education might explain a difference in appreciation between ministries and quangos of ‘obedience,’ while the orientation of such quangos on students, teachers and parents may account for a stronger emphasis on ‘responsiveness’ and ‘serviceability’. However, such explanations are somewhat opportunistic; further exploration of differences would be necessary to substantiate them. In the concluding section we will present some recommendations as to how to conduct such an exploration.

Effect of value congruence on trust

We can now use value incongruence, as measured in Table 6, to create a new variable and analyze its effect on the level of trust between quangos and ministries. To this end, we have created a dummy variable, which rates 1 if there is a significant incongruence on three or more values and 0 in all other cases.Footnote 5 We will use this dummy in the regression analyses (OLS) reported below. In these analyses we have also included the two aforementioned control variables: (1) the number of ZBOs belonging to the same ministry and (2) the age of the quango. The analysis so far has provided an additional argument to include these control variables, as we have learned that ZBOs have larger value incongruences than executive agencies.

We will begin this analysis with establishing the existing levels of trust; see Table 7. Quangos rate the level of trust between themselves and their parent ministry as 7.3 on a scale from 1 to 10. Executive agencies are more positive than ZBOs, but this difference is not statistically significant (t-test).

As the level of trust was only measured by asking quangos, the number of observations for the regression analyses reported in Table 8 is lower than in previous analyses. However, imputation of trust scores for the whole dataset did not render different results, so we have decided to stick with the original data as much as possible. Also, a separate analysis was carried out using the factor scores in Table 5, but that did not render any statistically significant effects either and therefore is not reported here.

Table 8 (model 1) shows that value incongruence leads to less trust, which corroborates hypothesis 2 (note that because the dummy variable measures value incongruence, the parameters in Table 8 should be reversed when interpreting the effects). However, when the control variables are included (model 2) this effect is no longer statistically significant. As stated before, ZBOs have higher value incongruence than executive agencies. The findings now seem to suggest that ZBOs have less trust, regardless of value incongruences. Further research is necessary to disentangle these effects (see also van Thiel & Yesilkagit, 2008).

Conclusions

There are but few empirical studies into value orientations in different parts of the (para)public sector (e.g., Lyons et al., 2006). Despite the shortcomings in our methodology—such as the matching of some operationalizations, the measurement of trust and the moderate response rates—the merger of our two data sets has offered us a unique opportunity to compare the organizational values of Dutch ministries and quangos, and examine the effects of value congruence on inter-organizational trust. More research on this topic is warranted, for two reasons. First, more knowledge needs to be obtained with regard to how, why, and to what extent values differ between different parts of the (para)public sector, because this has important implications for attempts to infuse more public sector value congruence, for instance through mandatory codes of conduct (cf. Lyons et al., 2006; Maesschalck et al. 2008). Second, trust can be expected to play an important role in the relationship between ministries and quangos (Rommel & Christiaens, 2009; van Thiel & Yesilkagit, 2008; Pollitt, 2005). It is important that ministries build and maintain good relationships with the ever-growing number of quangos that carry out tasks on their behalf, which are considered a major source of information for the development of new policies and the ministerial accountability to parliament (‘t Hart & Wille, 2006; Pollitt et al., 2004; OECD, 2002, Kickert, 2001).

So, what did we find? The central question of this study was: What is the degree of congruence between the organizational values of ministries and their quangos in the Netherlands, and what is the effect of value congruence on the trust between ministries and quangos?

Our findings show that parent ministries and quangos do not differ in their appreciation of what they consider to be the most important values: ‘incorruptibility’, ‘accountability’ and ‘honesty’. Therefore, ministries and quangos are to a large extent ‘birds of a feather’. However, there are also (significant) different value ratings, in particular with regard to ‘business-like’ values such as ‘serviceability’, ‘profitability’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘innovativeness’. All in all, hypothesis 1—presupposing a higher appreciation of NPM or businesslike values by quangos—is confirmed by our findings, although the effects are not the same for all hypothesized values or for both types of quangos. In particular, the appreciation of ‘efficiency’ merits further explanation.

Clearly, there is not one single conclusion as to whether there is value congruence between parent ministries and their—more or less—independent bodies: in fact, the results show ‘degrees of value congruence.’ Although the maximum number of values that show significant differences is 5, the data show different patterns with respect to incongruence on specific values, which leads to the conclusion that additional studies into the value congruence between specific departments and their quangos are paramount.

Our analyses were somewhat hindered by the fact that almost all values listed in Table 2 were considered important by the respondents. Further analysis of the relations between values is necessary—perhaps by using the type of network analysis as suggested by Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007), or by extending and improving the factor analysis we presented in Table 5. This holds in particular for the specific role different types of values play in different types of decision making. Because our sample consisted mainly of high-level managers and executives, it can be expected that they had important, strategic decisions in mind when prioritizing the importance of values in those decisions. However, this might not automatically be the case for other groups of respondents, so the operationalizations of values and decisions is an issue that merits consideration in future research endeavors.

Second, value congruence and the level of trust reported by quangos clearly coincide, confirming hypothesis 2. This effect is most strong for executive agencies which are closest to parent ministries (less formal autonomy, always originating from a ministry). It makes sense that quangos which are at less distance share more values with ministries, and therefore report more trust, because frequent interactions are predicted to induce more trust (Koivumaki & Mamia, 2006; Nooteboom, 2002; Reed, 2001; Lane and Bachmann 1996; Kramer, 1999). Thus, ministries and executive agencies are more ‘birds of a feather’ than ministries and ZBOs, or agencies and ZBOs for that matter. Moreover, executive agencies and ministries also ‘flock together’ more than ministries and ZBOs.

Trust is expected to improve the quality and effectiveness of relationships between ministries and quangos. The quality of the relationship can in turn be expected to contribute to the ability of parent ministries to steer or control quangos and ultimately achieve policy outcomes (Rommel & Christiaens, 2009; Pollitt, 2005). Therefore, both value incongruence and trust should be studied more in-depth. Such (qualitative) analysis at the meso-level could help to explain not only that differences exist but also why, when and how these differences become manifest (cf. Boyne 2002; van der Wal 2008). In turn, such knowledge could help to explain—or improve—existing problems in ministry-quango relationships.

Notes

The Netherlands are a decentralized unitary state, headed by the Queen. Parliament consists of two chambers, of which only the second chamber is directly elected through a system of proportional representation without a threshold. As a result, the Netherlands are always governed by two or three party coalitions (consensus seeking; see Andeweg & Irwin, 2005).

For some quangos ministerial accountability is limited to (1) the policy being implemented by the quango, (2) the decision to establish a quango and (3) supervision. Daily operations are formally no longer the responsibility of the minister. However, parliament retains the right to ask questions and does so on occasion. In some incidents this has led to interventions on matters which are formally no longer the minister’s responsibility (cf. van Thiel, 2001).

The survey is part of an international project (see www.soc.kuleuven.be/io/cost for more information).

One can think of another line of reasoning as well. The presence of many quangos/ZBOs within the domain of a specific ministry could be conducive to trust—because ministries become more experienced in maintaining relationships—but could also threaten the level of trust—because quangos have to share the ministries’ attention. We have no a priori expectation about these effects, except a general expectation that these control variables might play a role and therefore need to be included into the analyses.

A scale variable was also tested (high, medium, low) but did not lead to different results than reported here.

References

Allix, M., & van Thiel, S. (2005). Mapping the field of quasi-autonomous organizations in France and Italy. International Journal of Public Management, 8(1), 39–55.

Andeweg, R., & Irwin, G. (2005). Governance and politics of the Netherlands, 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Beck Jørgensen, T. (2006). Public Values, their Nature, Stability and Change: The Case of Denmark. Public Administration Quarterly, 30(4), 365–398.

Beck Jørgensen, T., & Bozeman, B. (2002). Public Values Lost? Comparing cases on contracting out from Denmark and the United States. Public Management Review, 4(1), 63–81.

Beck Jørgensen, T., & Bozeman, B. (2007). The Public Values Universe: An Inventory. Administration & Society, 39(3), 354–381.

Bowman, J. S., & Knox, C. C. (2008). Ethics in Government: No Matter How Long and Dark the Night. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 625–637.

Boyne, G. A. (2002). Public and private management: What’s the difference? Journal of Management Studies, 39(1), 97–122.

Boyne, G. A., Farrell, C., Law, J., Powell, M., & Walker, R. M. (2003). Evaluating public management reforms. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Christensen, T., & Laegreid, P. (Eds.). (2003). New Public Management: the transformation of ideas and practice. Ashgate Publishing Ltd: Aldershot.

Christensen, T., & Laegreid, P. (Eds.). (2006). Autonomy and regulation: coping with quangos in the modern state. Edward Elgar: Basingstoke.

Dasgupta, S. (1998). Trust as a commodity. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and Breaking Co-Operative Relations (pp. 49–72). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47.

De Bruijn, H., & Dicke, W. (2006). Strategies for Safeguarding Public Values in Liberalized Utility Sectors. Public Administration, 84(3), 717–735.

Edelenbos, J., & Klijn, E.-H. (2007). Trust in Complex Decision-Making Networks. Administration & Society, 39(1), 25–50.

Eikenberry, A. M., & Kluver, J. D. (2004). The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: Civil Society at Risk? Public Administration Review, 64(2), 132–140.

Ethicon. (2003). Gedragscodes binnen overheidsinstellingen. [Codes of conduct within governmental organizations] www.ovia.nl/dossiers/intoverheid/ codeoverheidsinstellingenverslag.ppt

Frederickson, H. G. (2005). Public ethics and the new managerialism: An axiomatic theory. In H. G. Frederickson & R. K. Ghere (Eds.), Ethics in public management (pp. 165–183). London: M.E. Sharpe.

Goss, R. P. (2003). What ethical conduct expectations do legislators have for the career bureaucracy? Public Integrity, 5(2), 93–112.

Greve, C., Flinders, M. V., & van Thiel, S. (1999). Quangos: what's in a name? Defining quasi-autonomous bodies from a comparative perspective. Governance, 12, 129–146.

Hood, C. C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–20.

Hood, C. C. (1995). The “New Public Management” in the 1980’s: Variations on a Theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(3), 93–109.

James, O. (2001). Business models and the transfer of businesslike central government agencies. Governance, 14(2), 233–252.

James, O. (2003). The executive agency revolution in Whitehall: public interest versus bureau-shaping perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kaptein, M., & Wempe, J. (2002). The balanced company: A theory of corporate integrity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kernaghan, K. (2000). The post-bureaucratic organization and public service values. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 66(1), 91–104.

Kernaghan, K. (2003). Integrating values into public service: The values statement as centerpiece. Public Administration Review, 63(6), 711–719.

Kickert, W. J. M. (2001). Public management of hybrid organizations: governance of quasi-autonomous quangos. International Public Management Journal, 4, 135–150.

Kickert, W. J. M. (2004). The history of governance in the Netherlands: continuity and exceptions. The Hague: Reed Elsevier.

Kim, H. S. (2001). Structure and Ethics Attitudes of Public Officials. Public Integrity, 3(4), 69–86.

Koivumaki, J. & T. Mamia. (2006). Reciprocity as a Source of Vertical Trust at Workplaces. Paper presented at Conference of International Sociological Association, Durban, South Africa

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598.

Krippendorf, K. (1981). Content analysis. London: Sage.

Lane, J.-E. (2000). New Public Management. London: Routledge.

Lane, Ch, & Bachmann, R. (1996). The social constitution of trust: supplier relations in Britain and Germany. Organization Studies, 17, 365–395.

Langfred, C. W. (2004). Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and in-dividual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 385–399.

Lyons, S. T., Duxbury, L. E., & Higgins, C. A. (2006). A comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public sector, and parapublic sector employees. Public Administration Review, 66(4), 605–618.

Maesschalck, J. (2004). The impact of the new public management reforms on public servants’ ethics: Towards a theory. Public Administration, 82(2), 465–489.

Maesschalk, J., van der Wal, Z., & Huberts, L. W. J. C. (2008). Public Service Motivation and Ethical Conduct. In J. Perry & A. Hondeghem (Eds.), Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service (pp. 157–176). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Noordegraaf, M., & Abma, T. (2003). Management by Measurement? Public management practices amidst ambiguity. Public Administration, 81(4), 853–871.

Nooteboom, B. (2002). Trust: Forms, Foundations, Functions, Failures and Figures. Cheltenham: Ed-ward Elgar.

OECD. (2002). Distributed public governance: agencies, authorities and other government bodies. Paris: OECD Press.

Pollitt, C. (2005). Ministries and agencies: steering, meddling, neglect and dependency. In M. Painter & J. Pierre (Eds.), Challenges to state policy capacity: global trends and comparative perspectives (pp. 112–136). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Pollitt, C., Talbot, C., Caulfield, J., & Smullen, A. (2004). Quangos: how governments do things through semi-autonomous organizations. Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke.

Pollitt, C., & Talbot, C. (Eds.). (2004). Unbundled government: a critical analysis of the global trend to agencies, quangos and contractualisation. Routledge: London.

Posner, B. Z., & Schmidt, W. H. (1984). Values and the American manager: An update. California Management Review, 26(3), 202–216.

Reed, M. I. (2001). Organization, trust and control: a realist analysis. Organization Studies, 22, 201–228.

Rommel, J., & Christiaens, J. (2009). Steering from ministers and departments: coping strategies of agencies in Flanders. Public Management Review, 11(1), 79–100.

Rosenbloom, D. (1983). Public administration theory and the separation of powers. In J. M. Shafritz, A. C. Hyde, & S. J. Parkes (Eds.), Classics in public administration (5th ed., pp. 446–457). California, Belmont.

Schmidt, W. H., & Posner, B. Z. (1986). Values and expectations of federal service executives. Public Administration Review, 46(4), 447–454.

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A Theory of Cultural Values and Some Implications for Work. Applied Psychology, 48(1), 23–47.

t’Hart, P., & Wille, A. (2006). Ministers and top officials in the Dutch core executive: living together, growing apart? Public Administration, 84, 121–146.

van den Heuvel, J. H. J., Huberts, L. W. J. C., & Verberk, S. (2002). Het morele gezicht van de overheid. Waarden, normen en beleid [The moral face of government. Values, norms and policy]. Utrecht: Lemma.

van der Wal, Z. (2008). Value solidity: differences, similarities and conflicts between the organizational values of governments and business. Dissertation, Amsterdam, VU.

van der Wal, Z., de Graaf, G., & Lasthuizen, K. (2008). What’s valued most? A comparative empirical study on the differences and similarities between the organizational values of the public and private sector. Public Administration, 86(2), 465–482.

van der Wal, Z., & Huberts, L. W. J. C. (2008). Value solidity in government and business: Results of an empirical study on public and private sector organizational values. American Review of Public Administration, 38(3), 264–285.

van der Wal, Z., Huberts, L. W. J. C., van den Heuvel J. H. J. & Kolthoff E. W. (2006). Central values of government and business: Differences, similarities and conflicts. Public Administration Quarterly, 30(3), 314–364.

van der Wal, Z., & van Hout, E. J. Th. (2009). Is public value pluralism paramount? The intrinsic hybridity and multiplicity of public values. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3), 220–231.

van Hout, E., & Th, J. (2007). Zorg in Spagaat [Healthcare in Splits]. Den Haag: Lemma.

van Thiel, S. (2004). Trends in the public sector: Explaining the increased use of quasi-autonomous bodies in policy implementation. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 16(2), 175–201.

van Thiel, S. (2006). Styles of reform: Differences in agency creation between policy sectors in the Netherlands. Journal of Public Policy, 26(2), 115–139.

van Thiel, S., & Pollitt, C. (2007). The management and control of executive agencies: An Anglo-Dutch comparison. In C. Pollitt, S. van Thiel, & V. Homburg (Eds.), New public management In Europe: Adaptation and alternatives (pp. 52–70). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

van Thiel, S., & Yesilkagit, K. (2006). Respondentenrapport Cobra Enquête. (Internal report, in Dutch). Rotterdam en Utrecht.

Van Thiel, S. & Yesilkagit, K. (2007). Good neighbors or distant friends: Relationships between executive agencies and ministries. Paper presented at ECPR Conference, SG on Regulation, 5–8 September 2007, Pisa, Italy.

Van Wart, M. (1998). Changing public sector values. New York &London: Garland Publishing.

Veenswijk, M., & Hakvoort, J. L. M. (2002). Public-private transformations. Institutional shifts, cultural changes and altering identities: Two case studies. Public Administration, 80, 543–555.

Vrangbaek, K. (2009). Public Sector Values in Denmark. A Survey Analysis. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(6), 508–535.

Yesilkagit, A. K., & van Thiel, S. (2008). Political influence and bureaucratic autonomy. Public Organization Review, 8(2), 137–154.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Thiel, S., van der Wal, Z. Birds of a Feather? The Effect of Organizational Value Congruence on the Relationship Between Ministries and Quangos. Public Organiz Rev 10, 377–397 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-010-0112-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-010-0112-9