Abstract

Background

Perforated peptic ulcer (PPU), despite antiulcer medication and Helicobacter eradication, is still the most common indication for emergency gastric surgery associated with high morbidity and mortality. Outcome might be improved by performing this procedure laparoscopically, but there is no consensus on whether the benefits of laparoscopic closure of perforated peptic ulcer outweigh the disadvantages such as prolonged surgery time and greater expense.

Methods

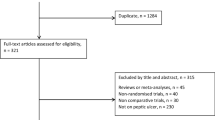

An electronic literature search was done by using PubMed and EMBASE databases. Relevant papers written between January 1989 and May 2009 were selected and scored according to Effective Public Health Practice Project guidelines.

Results

Data were extracted from 56 papers, as summarized in Tables 1–7. The overall conversion rate for laparoscopic correction of perforated peptic ulcer was 12.4%, with main reason for conversion being the diameter of perforation. Patients presenting with PPU were predominantly men (79%), with an average age of 48 years. One-third had a history of peptic ulcer disease, and one-fifth took nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Only 7% presented with shock at admission. There seems to be no consensus on the perfect setup for surgery and/or operating technique. In the laparoscopic groups, operating time was significant longer and incidence of recurrent leakage at the repair site was higher. Nonetheless there was significant less postoperative pain, lower morbidity, less mortality, and shorter hospital stay.

Conclusion

There are good arguments that laparoscopic correction of PPU should be first treatment of choice. A Boey score of 3, age over 70 years, and symptoms persisting longer than 24 h are associated with higher morbidity and mortality and should be considered contraindications for laparoscopic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Since the late 1980s, laparoscopy has become increasingly popular. In the beginning laparoscopy was mainly used for elective surgery since it was not clear what the influence was of the pneumoperitoneum on the acute abdomen with peritonitis. However the benefits of laparoscopy with regard to the acute abdomen as a diagnostic tool have been established since, and also its therapeutic possibilities seem to be advantageous [1–3]. The rapid development of laparoscopic surgery has further complicated the issue of the best approach for the management of perforated peptic ulcer (PPU) [4]. PPU is a condition in which laparoscopic repair is an attractive option. Not only is it possible to identify the site and pathology of the perforation, but the procedure also allows closure of the perforation and peritoneal lavage, just like in open repair but without a large upper abdominal incision [5, 6]. Nonetheless, not all patients are suitable for laparoscopic repair [5]. Despite many trials (mostly nonrandomized or retrospective), the routine treatment for perforated peptic ulcer still seems to be by upper laparotomy, representing the main motive for reviewing the literature and summarizing all (significant) results.

Materials and methods

An extensive electronic literature search was done by using PubMed and EMBASE databases. Keywords used for searching were “laparoscopic,” “correction,” “repair,” and “peptic ulcer.” All papers in English or German language published between January 1989 and May 2009 were included. Papers were scored according to Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) guidelines as advised in Jackson’s guidelines for systematic reviews [7]. Using this rating system each paper was classified as weak, moderate or strong.

Results

Fifty-six relevant articles were found by PubMed and EMBASE search. Of these, 36 were prospective or retrospective trials, 5 were review articles, 3 articles described new techniques making laparoscopic correction of PPU more accessible, and 12 were general, of which 1 was the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) guideline [1–6, 8–57]. Study details are listed in Table 1. Based on patient details and selection criteria as reported in these papers a general overview could be made of the average symptoms of a patient presenting with acute abdominal pain suspected for PPU, and of the results of additional diagnostic tools such as X-ray and blood sample (Table 2). Three papers published results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [29, 46, 57]. Since these were the only RCTs comparing laparoscopic repair with open repair for PPU, their results have been listed separately in Table 3. All three showed significant reduction in postoperative pain in the laparoscopic group, and Siu et al. concluded that morbidity was significant lower in the laparoscopic group [29]. Two of these RCT’s concluded that operating time was significant longer, though the other group showed a significant shorter operating time. In 29 studies the surgical technique used for laparoscopic correction of PPU was mentioned in the “Material and Methods” section. These details are summarized in Table 4. Table 5 gives an overview of the total amount of complications observed after surgery for PPU by either laparoscopic technique or open closure. It is noticeable that the incidence of scar problems after surgery for PPU was as high as 9.9%. Also, mortality after surgery for peptic ulcer disease, despite all technical and medical improvement, was still 5.8%. The average conversion rate was 12.4% (Table 1). Reasons for conversion are listed in Table 6. The three most common reasons for conversion were size of perforation (often >10 mm), inadequate ulcer localization, and difficulties placing reliable sutures due to friable edges. Table 7 compares results between laparoscopic and open repair with regard to most important parameters such as postoperative pain, bowel action, hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality. Finally, Table 8 gives an overview of the conclusions drawn by 40 papers.

Discussion

In 2002, Lagoo et al. added the sixth decision for a surgeon to be make regarding PPU to the existing five therapeutic decisions proposed by Feliciano in 1992 [4]. The first decisions were about the need for surgical or conservative treatment, to use omentoplasty or not, the condition of the patient to undergo surgery, and which medication should be given. The sixth decision was: “Are we going to perform this procedure laparoscopically or open?” Is there really a sixth decision to be made, or are there enough proven benefits of laparoscopic correction that this should not be a question anymore? Reviewing literature showed that much research has been done, although not many prospective randomized trials have been performed (n = 3). Still, data extracted from these papers are interesting.

Patient characteristics

Often it was mentioned that age of patients presenting with PPU is increasing, due to better medical antiulcer treatment and also because of more NSAID and aspirin usage in the elderly population [4, 17, 56]. The results in Table 2 show that the average age of patients with PPU was 48 years and that only 20% of these patients had used NSAIDs. One-third of patients had a history of peptic ulcer. Although Helicobacter pylori is known to be present in about 80% of patients with PPU, this might indicate that there are more factors related to PPU for which the pathology is not yet clear [4]. Sixty-seven percent of perforations were located in the duodenum and only 17% were gastric ulcers (Table 2), according to findings in literature [58]. In 85% there was free air visible on X-ray (Table 2), which supports the diagnosis, but free air could be caused by other perforations as well and, although the diagnosis of PPU is not difficult to make, sometimes there is a good indication for diagnostic laparoscopic to exclude other pathology [2]. In 93–98%, definitive diagnosis could be made by performing diagnostic laparoscopy in the patient with an abdominal emergency, of which 86–100% could be treated laparoscopically during the same session [1, 2].

Surgical technique

There seems to be no consensus on how to perform the surgical procedure, which probably means that the perfect setup has not yet been found. Forty-four percent of surgeons preferred to stand between the patient’s legs, while 33% performed the procedure at the patient’s left side. Also, the number, position, and size of trocars differed between surgeons. Placing and tying sutures was more demanding laparoscopically, and two techniques were used (Table 4). Theoretically there is a preference for intracorporeal knotting over extracorporeal suturing, because the latter is likely to cut through the friable edge of the perforation [12]. One of the disadvantages of laparoscopic correction of PPU often mentioned was the significant longer operating time, which causes more costs and may be nonpreferable in a hemodynamically unstable patient [5, 16, 18, 35, 42, 43, 45, 46]. Ates et al. presented results with simple suture repair of PPU without using pedicled omentoplasty [11]. This significantly shortened operating time, but the question remains of whether it is safe to abandon omentoplasty completely. Cellan-Jones emphasized the necessity for omentoplasty [59]. His advised technique, to prevent tearing out of sutures and prevent enlargement of the size of perforation by damaging the friable edges, is to place a plug of pedicled omentum into the “hole” and secure this with three tie-over sutures. His technique is often called the Graham patch, but Graham describes in his article the use of a free omental plug, a technique that hardly any surgeon uses nowadays [60]. It might be less confusion to use the term “pedicled omentoplasty.” The usefulness of pedicled omentoplasty has been emphasized by others, and Schein even stated: “first suturing the hole and then sticking omentum over the repair is wrong, if you cannot patch it, then you must resect” [59, 61]. Avoiding omentoplasty might shorten operating time but might be the reason for a higher incidence of leakage at the repaired ulcer side [5, 24]. Another reason for longer operating time during the laparoscopic procedure might be the irrigation procedure. Peritoneal lavage is one of the key interventions in the management of PPU [4]. Lavage was performed with 2–6 L warm saline, but even up to 10 L has been described (Table 3) [4]. By using a 5-mm or even 10-mm suction device, this part of surgery took even up to 58 min [30]. Whether generous irrigation is really necessary has not yet been proven.

Patient selection

Not all patients are suitable for laparoscopic repair, and it is important to preselect patients who are good candidates for laparoscopic surgery [5]. Boey’s classification appears to be a helpful tool in decision-making [4, 56]. The Boey score is a count of risk factors, which are: shock on admission, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade III–V, and duration of symptoms [52]. The maximum score is 3, which indicates high surgical risk. Laparoscopic repair is reported only to be safe with Boey score 0 and 1 [16, 42]. Since the incidence of patients with Boey score 2 and 3 is low (according to Table 2, only 2% of patients were admitted with Boey score 3, 7% were in shock at admission, and 11% had prolonged symptoms for more than 24 h) and Boey 2 and 3 is associated with high morbidity and mortality rate anyway, independent of type of surgery, it is difficult to find significant foundation for this statement. Other reported contraindications are age >70 years and perforation larger than 10 mm in diameter [16, 17, 32, 33].

Reasons for conversion

Overall conversion rate was 12.4%, with a range of 0–28.5% (Table 1). The most common reason for conversion was the size of perforation, but by using an omental patch this might not necessarily have to be a reason anymore to convert. From literature it was already known that other common reasons for conversion include failure to locate the perforation [17]. Shock at admission was associated with a significant higher conversion rate (50% versus 8%) [4]. Furthermore, time lapse between perforation and presentation negatively influenced conversion rate (33% versus 0%) [4].

Complications

The best parameters to compare two different surgical techniques are morbidity and mortality. PPU is still associated with high morbidity and mortality, with main problems caused by wound infection, sepsis, leakage at the repair site, and pulmonary problems (Table 4) [56]. Comparing results shows a remarkable difference in morbidity (14.3% in the laparoscopic group versus 26.9% in the open group) and mortality (3.6% versus 6.4%) (Table 6). Many trials measured the amount of postoperative opiate usage, but since this was scored in different ways (days used, number of injections, amount of opiates in mg) these data were not comparable. However, overall, many studies showed significant reduction in pain, mortality, morbidity, wound infection, resuming normal diet, and hospital stay (Tables 6 and 7). Of course there are some negative results which cannot be ignored (Table 7). Three papers reported a significant higher incidence of suture leakage, associated in one with a higher incidence of reoperations, but leakage mainly occurred in the sutureless repair group or in the group in which (pedicled) omentoplasty was not routinely used [18, 24, 32].

Overall there seems to be significant proof of the benefits of laparoscopic repair, but it is technical demanding surgery which needs a surgeon experienced with laparoscopy [4, 17]. CO2 insufflation of the peritoneal cavity in the presence of peritonitis has been shown in rat models to cause an increase in bacterial translocation [4]. This led to the assumption that laparoscopic surgery might be dangerous in patients with prolonged peritonitis. Vaidya et al. performed laparoscopic repair in patients with symptoms of PPU for more than 24 h and concluded that it was safe even in patients with prolonged peritonitis, which has been confirmed by others [4, 8, 39, 44].

Alternative techniques

Closing the perforation site using suture repair is challenging, which is why alternative methods have been described [5, 15, 21, 24, 25, 31]. Examples are represented by the sutureless repair of PPU, in which the perforation is closed by a gelatin sponge glued into the perforation or the perforation is closed by fibrin glue. Song et al. proposed the simple “one-stitch” repair with omental patch [9]. The automatic stapler has been used for perforation site closure, use of running suture was suggested to avoid intracorporeal or extracorporeal knotting, and combined laparoscopic–endoscopic repair has been described as well [21].

Definitive ulcer surgery

The need for definitive surgical management of peptic ulcer disease has markedly decreased, but 0–35% of patients admitted for PPU received definitive ulcer surgery [8, 16, 20, 56]. Definitive ulcer surgery can be performed safely with laparoscopic techniques [4, 12, 36]. Palanivelu et al. performed definitive surgery in 10% of cases admitted for PPU. All procedures (posterior truncal vagotomy and anterior highly selective vagotomy) were performed laparoscopically without conversion or mortality [12].

Research

A few aspects regarding laparoscopic repair of PPU are still unclear, and further research on these topics would be interesting. One of the remaining questions is whether there is less formation of intra-abdominal adhesions after laparoscopic repair [4]. If this is the case, it would be another convincing reason to perform this procedure laparoscopically. Often mentioned as one of the major disadvantages of laparoscopic surgery are the high costs, caused by the need for more surgical staff and laparoscopic equipment. However no specified calculation of per- and postoperative costs have been made so far, and also the costs saved by possible earlier return to work have to be taken into account.

To conclude, the results of this review support the statement of the EAES already made in 2006 that, in case of suspected perforated peptic ulcer, laparoscopy should be advocated as diagnostic and therapeutic tool [14].

References

Ates M, Coban S, Sevil S, Terzi A (2008) The efficacy of laparoscopic surgery in patients with peritonitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 18:453–456

Agresta F, Mazzarolo G, Ciardo LF, Bedin N (2008) The laparoscopic approach in abdominal emergencies: has the attitude changed? A single-center review of a 15-year experience. Surg Endosc 22:1255–1262

Sanabria AE, Morales CH, Villegas MI (2005) Laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004778

Lagoo S, McMahon RL, Kakihara M, Pappas TN, Eubanks S (2002) The sixth decision regarding perforated duodenal ulcer. JSLS 6:359–368

Lau WY (2002) Perforated peptic ulcer: open versus laparoscopic repair. Asian J Surg 25:267–269

Druart ML, Van Hee R, Etienne J, Cadière GB, Gigot JF, Legrand M, Limbosch JM, Navez B, Tugilimana M, Van Vyve E, Vereecken L, Wibin E, Yvergneaux JP (1997) Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcer. A prospective multicenter clinical trial. Surg Endosc 11:1017–1020

Jackson N, Waters E (2005) Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promotion Int 20:367–374

Vaidya BB, Garg CP, Shah JB (2009) Laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer with delayed presentation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 19(2):153–156

Song KY, Kim TH, Kim SN, Park CH (2008) Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcers: the simple “one-stitch” suture with omental patch technique. Surg Endosc 22:1632–1635

Bhogal RH, Athwal R, Durkin D, Deakin M, Cheruvu CN (2008) Comparison between open and laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer disease. World J Surg 32:2371–2374

Ates M, Sevil S, Bakircioglu E, Colak C (2007) Laparoscopic repair of peptic ulcer perforation without omental patch versus conventional open repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:615–619

Palanivelu C, Jani K, Senthilnathan P (2007) Laparoscopic management of duodenal ulcer perforation: is it advantageous? Indian J Gastroenterol 26:64–66

Wong BP, Chao NS, Leung MW, Chung KW, Kwok WK, Liu KK (2006) Complications of peptic ulcer disease in children and adolescents: minimally invasive treatments offer feasible surgical options. J Pediatr Surg 41:2073–2075

Sauerland S, Agresta F, Bergamaschi R, Borzellino G, Budzynski A, Champault G, Fingerhut A, Isla A, Johansson M, Lundorff P, Navez B, Saad S, Neugebauer EA (2006) Laparoscopy for abdominal emergencies: evidence-based guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery. Surg Endosc 20:14–29

Lam PW, Lam MC, Hui EK, Sun YW, Mok FP (2005) Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcers: the”three-stitch” Graham patch technique. Surg Endosc 19:1627–1630

Lunevicius R, Morkevicius M (2005) Comparison of laparoscopic versus open repair for perforated duodenal ulcers. Surg Endosc 19:1565–1571

Lunevicius R, Morkevicius M (2005) Management strategies, early results, benefits, and risk factors of laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer. World J Surg 29:1299–1310

Lunevicius R, Morkevicius M (2005) Systematic review comparing laparoscopic and open repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 92:1195–1207

Lunevicius R, Morkevicius M (2005) Risk factors influencing the early outcome results after laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcer and their predictive value. Langenbecks Arch Surg 390:413–420

Kirshtein B, Bayme M, Mayer T, Lantsberg L, Avinoach E, Mizrahi S (2005) Laparoscopic treatment of gastroduodenal perforations: comparison with conventional surgery. Surg Endosc 19:1487–1490

Alvarado-Aparicio HA, Moreno-Portillo M (2004) Multimedia article: management of duodenal ulcer perforation with combined laparoscopic and endoscopic methods. Surg Endosc 18:1394

Tsumura H, Ichikawa T, Hiyama E, Murakami Y (2004) Laparoscopic and open approach in perforated peptic ulcer. Hepatogastroenterology 51:1536–1539

Malkov IS, Zaynutdinov AM, Veliyev NA, Tagirov MR, Merrell RC (2004) Laparoscopic and endoscopic management of perforated duodenal ulcers. J Am Coll Surg 198:352–355

Lau H (2004) Laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 18:1013–1021

Siu WT, Chau CH, Law BK, Tang CN, Ha PY, Li MK (2004) Routine use of laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 91:481–484

Gentileschi P, Rossi P, Manzelli A, Lirosi F, Susanna F, Stolfi VM, Spina C, Gaspari AL (2003) Laparoscopic suture repair of a perforated gastric ulcer in a severely cirrhotic patient with portal hypertension: first case report. JSLS 7:377–382

Seelig MH, Seelig SK, Behr C, Schonleben K (2003) Comparison between open and laparoscopic technique in the management of perforated gastroduodenal ulcers. J Clin Gastroenterol 37:226–229

Aali AYA, Bestoun HA (2002) Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcer. Middle East J Emerg Med 2:1–4

Siu WT, Leong HT, Law BK, Chau CH, Li AC, Fung KH, Tai YP, Li MK (2002) Laparoscopic repair for perforated peptic ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 235:313–319

Arnaud JP, Tuech JJ, Bergamaschi R, Pessaux P, Regenet N (2002) Laparoscopic suture closure of perforated duodenal peptic ulcer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 12:145–147

Wemyss-Holden S, White SA, Robertson G, Lloyd D (2002) Color coding of sutures in laparoscopic perforated duodenal ulcer: a new concept. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 12:177–179

Lee FY, Leung KL, Lai PB, Lau JW (2001) Selection of patients for laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 88:133–136

Lee FY, Leung KL, Lai BS, Ng SS, Dexter S, Lau WY (2001) Predicting mortality and morbidity of patients operated on for perforated peptic ulcers. Arch Surg 136:90–94

Bohm B, Ablassmaier B, Muller JM (2001) Laparoscopic surgery of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Chirurg 72:349–361

Millat B, Fingerhut A, Borie F (2000) Surgical treatment of complicated duodenal ulcers: controlled trials. World J Surg 24:299–306

Dubois F (2000) New surgical strategy for gastroduodenal ulcer: laparoscopic approach. World J Surg 24:270–276

Freston JW (2000) Management of peptic ulcers: emerging issues. World J Surg 24:250–255

Agresta F, Michelet I, Coluci G, Bedin N (2000) Emergency laparoscopy: a community hospital experience. Surg Endosc 14:484–487

Robertson GS, Wemyss-Holden SA, Maddern GJ (2000) Laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcers. The role of laparoscopy in generalised peritonitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 82:6–10

Khoursheed M, Fuad M, Safar H, Dashti H, Behbehani A (2000) Laparoscopic closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. Surg Endosc 14:56–58

Kabashima A, Maehara Y, Hashizume M, Tomoda M, Kakeji Y, Ohno S, Sugimachi K (1998) Laparoscopic repair of a perforated duodenal ulcer in two patients. Surg Today 28:633–635

Katkhouda N, Mavor E, Mason RJ, Campos GM, Soroushyari A, Berne TV (1999) Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcers: outcome and efficacy in 30 consecutive patients. Arch Surg 134:845–848; discussion 849–850

Bergamaschi R, Marvik R, Johnsen G, Thoresen JE, Ystgaard B, Myrvold HE (1999) Open vs laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcer. Surg Endosc 13:679–682

Lau JY, Lo SY, Ng EK, Lee DW, Lam YH, Chung SC (1998) A randomized comparison of acute phase response and endotoxemia in patients with perforated peptic ulcers receiving laparoscopic or open patch repair. American J Surg 175:325–327

So JB, Kum CK, Fernandes ML, Goh P (1996) Comparison between laparoscopic and conventional omental patch repair for perforated duodenal ulcer. Surg Endosc 10:1060–1063

Lau WY, Leung KL, Kwong KH, Davey JC, Robertson C, Dawson JJ, Chung SC, Li AK (1996) A randomized study comparing laparoscopic versus open repair of perforated peptic ulcer using suture or sutureless technique. Ann Surg 224:131–138

Memon MA (1995) Laparoscopic omental patch repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Surg 222:761–762

Matsuda M, Nishiyama M, Hanai T, Saeki S, Watanabe T (1995) Laparoscopic omental patch repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Surg 221:236–240

Lee KH, Chang HC, Lo CJ (2004) Endoscope-assisted laparoscopic repair of perforated peptic ulcers. Am Surg 70:352–356

Golash V, Willson PD (2005) Early laparoscopy as a routine procedure in the management of acute abdominal pain: a review of 1, 320 patients. Surg Endosc 19:882–885

Rossi S (2005) Laparoscopy in gastrointestinal emergency. Eur Surgery 36:15–18

Boey J, Wong J (1987) Perforated duodenal ulcers. World J Surg 11:319–324

Urbano D, Rossi M, De Simone P, Berloco P, Alfani D, Cortesini R (1994) Alternative laparoscopic management of perforated peptic ulcers. Surg Endosc 8:1208–1211

Miserez M, Eypasch E, Spangenberger W, Lefering R, Troidl H (1996) Laparoscopic and conventional closure of perforated peptic ulcer. A comparison. Surg Endosc 10:831–836

Bloechle C, Emmermann A, Zornig C (1997) Laparoscopic and conventional closure of perforated peptic ulcer. Surg Endosc 11:1226–1227

Lohsiriwat V, Prapasrivorakul S, Lohsiriwat D (2009) Perforated peptic ulcer: clinical presentation, surgical outcomes, and the accuracy of the Boey scoring system in predicting postoperative morbidity and mortality. World J Surg 33:80–85

Bertleff MJ, Halm JA, Bemelman WA, van der Ham AC, van der Harst E, Oei HI, Smulders JF, Steyerberg EW, Lange JF (2009) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of the perforated peptic ulcer: the LAMA trial. World J Surg 33(7):1368–1373

Zittel TT, Jehle EC, Becker HD (2000) Surgical management of peptic ulcer disease today–indication, technique and outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg 385:84–96

Cellan-Jones CJ (1929) A rapid method of treatment in perforated duodenal ulcer. BMJ 1076–1077

Graham R, R (1937) The treatment of perforated duodenal ulcers. Surg Gynecol Obstet 235–238

Schein M (2005) Perforated peptic ulcer. In: Schein’s common sense emergency abdominal surgery: Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 143–150

Disclosures

Mariëtta Bertleff and Johan Lange have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertleff, M.J.O.E., Lange, J.F. Laparoscopic correction of perforated peptic ulcer: first choice? A review of literature. Surg Endosc 24, 1231–1239 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0765-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0765-z