Abstract

Background:

Ethnic minority groups in Western European countries tend to have higher levels of overweight than the majority populations for reasons that are poorly understood. Investigating relative differences between countries could enable an investigation of the importance of national context in determining these inequalities.

Objective:

To explore: (1) whether Indian and African origin populations in England and the Netherlands are similarly disadvantaged compared with the White populations in terms of the prevalence of overweight and central obesity; (2) whether the previously known Dutch advantage of relatively low overweight prevalence is also observed in Dutch ethnic minority groups and (3) the contribution of health behaviour and socio-economic position to the differences observed.

Methods:

Secondary analyses of population-based studies of 16 406 participants from England and the Netherlands. Prevalence ratios were estimated using regression models.

Results:

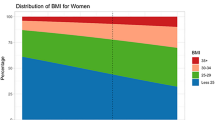

Except for African men, ethnic minority groups in both countries had higher rates of overweight and central obesity than their White counterparts. However, the Dutch minority groups were relatively more disadvantaged than English minority groups as compared with the majority populations. The Dutch advantage of the low prevalence of obesity was only seen in White men and women and African men. In contrast, English-Indian (prevalence ratio=0.87, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.81–0.93) and English-Caribbean (prevalence ratio=0.82, 95% CI: 0.76–0.89) women were less centrally obese than their Dutch equivalents. The Dutch-Indian men were very similar to the English-Indian men. The contribution of health behaviour and socio-economic position to the observed differences were small.

Conclusion:

Contrary to the patterns in White groups, the Dutch ethnic minority women were more obese than their English equivalents. More work is needed to identify factors that may contribute to these observed differences.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Visscher TL, Seidell JC . The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001; 22: 355–375.

Organisation for economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): http://www.irdes.fr/EcoSante/DownLoad/OECDHealthData_FrequentlyRequestedData.xls (visited on 25 November, 2008).

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000; 894: i–xii, 1–253.

Rabin BA, Boehmer TK, Brownson RC . Cross-national comparison of environmental and policy correlates of obesity in Europe. Eur J Public Health 2007; 17: 53–61.

Agyemang C, Addo J, Bhopal R, de-Graft Aikins A, Stronks K . Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and established risk factors among populations of sub-Saharan African descent in Europe: a literature review. Global Health 2009; 11: 5–7.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM . Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 2006; 295: 1549–1555.

Oldroyd J, Banerjee M, Heald A, Cruickshank K . Diabetes and ethnic minorities. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81: 486–490.

Bowie JV, Juon HS, Cho J, Rodriguez EM . Factors associated with overweight and obesity among mexican americans and central americans: results from the 2001 California health interview survey. Prev Chronic Dis 2007; 4: A10.

Dijkshoorn H, Nierkens V, Nicolaou M . Risk groups for overweight and obesity among Turkish and Moroccan migrants in The Netherlands. Public Health 2008; 122: 625–630.

Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Stronks K . Ethnic inequalities in health: does it matter where you have migrated to? Ethn Health 2010; 15: 216–218.

Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, Zaninotto P, Unwin N, Nazroo J et al. A cross-national comparative study of blood pressure and hypertension between English and Dutch South-Asian and African origin populations: the role of national context. Am J Hypertens 2010; 23: 639–648.

Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, Zaninotto P, Unwin N, Nazroo J et al. A cross-national comparative study of smoking prevalence and cessation between English and Dutch South Asian and African origin populations: the role of national context. Nicotine Tob Res 2010; 12: 557–566.

Bhopal R . Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004; 58: 441–445.

Agyemang C, Bhopal R, Bruijnzeels M . Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005; 59: 1014–1018.

Stronks K, Kulu-Glasgow I, Agyemang C . The utility of ‘country of birth’ for the classification of ethnic groups in health research: the Dutch experience. Ethn Health 2009; 14: 1–14.

Erens B, Primatesta P, Prior G (eds). Health Survey for England. The health of minority ethnic groups 1999. TSO: London, 2001.

Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Yallop J, Walker L, Alberti KG et al. Heterogeneity of coronary heart disease risk factors in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and European origin populations: cross sectional study. BMJ 1999; 319: 215–220.

Agyemang C, Bindraban N, Mairuhu G, Montfrans G, Koopmans R, Stronks K . Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among Black Surinamese, South Asian Surinamese and White Dutch in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: the SUNSET study. J Hypertens 2005; 23: 1971–1977.

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004; 363: 157–163.

Hsieh SD, Yoshinaga H, Muto T . Waist-to-height ratio, a simple and practical index for assessing central fat distribution and metabolic risk in Japanese men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 610–616.

Lamacchia O, Pinnelli S, Camarchio D, Fariello S, Gesualdo L, Stallone G et al. Waist-to-height ratio is the best anthropometric index in association with adverse cardiorenal outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Am J Nephrol 2009; 29: 615–619.

Ashwell M, Lejeune S, McPherson K . Ratio of waist circumference to height may be better indicator of need for weight management. BMJ 1996; 312: 377.

Henriksson KM, Lindblad U, Agren B, Nilsson-Ehle P, Rastam L . Associations between body height, body composition and cholesterol levels in middle-aged men: the coronary risk factor study in southern Sweden (CRISS). Eur J Epidemiol 2001; 17: 521–526.

Zhang Q, Wang Y . Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in US adults: 1971–2000. Obes Res 2004; 12: 1622–1632.

Schröder H, Morales-Molina JA, Bermejo S, Barral D, Mándoli ES, Grau M et al. Relationship of abdominal obesity with alcohol consumption at population scale. Eur J Nutr 2007; 46: 369–376.

Chiolero A, Jacot-Sadowski I, Faeh D, Paccaud F, Cornuz J . Association of cigarettes smoked daily with obesity in a general adult population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15: 1311–1318.

Nazroo J, Jackson J, Karlsen S, Torres M . The Black diaspora and health inequalities in the US and England: does where you go and how you get there make a difference? Sociol Health Illn 2007; 29: 811–830.

Gill PS, Kai J, Bhopal RS, Wild S . Health Care Needs Assessment: Black and Minority Ethnic Groups. In: Raftery J (ed.). Health Care Needs Assessment. The epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews. Third Series. Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd.: Abingdon, 2007, pp 227–239.

Sjöström M, Oja P, Hagströmer M, Smith BJ, Bauman A . Health-enhancing physical activity across European Union countries: the Eurobarometer study. J Public Health 2006; 14: 291–300.

Silventoinen K, Sans S, Tolonen H, Monterde D, Kuulasmaa K, Kesteloot H et al. WHO MONICA Project. Trends in obesity and energy supply in the WHO MONICA Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004; 28: 710–718.

Duyvené de Wit T, Koopmans R . The integration of ethnic minorities into political culture: The Netherlands, Germany and Great Britain Compared. Acta Politica 2005; 40: 50–73.

van Nierkerk M . Paradoxes in paradise. In: Vermeulen H, Penninx E (eds). Immigrant integration: the Dutch case. Het Spinhuis Publishers: Amsterdam, 2000, pp 64–92.

Flay BR, Burton D . Effective mass communication strategies for health campaigns. In: Atkin C, Wallack L (eds). Mass communication and public health: Complexities and conflicts. Sage: Newbury Park, CA, 1990, pp 129–146.

Agyemang C, Kunst AE, Bhopal R, Zannonito P, Anujuo K, Unwin N et al. Comparison between England and the Netherlands of fasting glucose and diabetes South Asian and African origin populations: does it matter where you have migrated to? Eur J Public Health 2010; 20 (Suppl 1): S84.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a VENI fellowship (Grant number 916.76.130) awarded by the Board of the Council for Earth and Life Sciences (ALW) of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Note on ethnic categories

Appropriate terms for the scientific study of health by ethnicity are under discussion.13 Different terms are used to refer to populations of South-Asian origin and African origin living in different European countries.13, 14, 15 In the United Kingdom, the term South-Asian refers to populations originating from the Indian Sub-continent, effectively, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. African-Caribbean refers to people, and their offspring, with African ancestral origin, but who migrated to the United Kingdom from the Caribbean islands. The migration of these populations to the United Kingdom in the mid-20th century was mainly because of the need to rebuild United Kingdom following World War II. The demands of an expanding economy and the development of the welfare state required labour on a scale that could not be provided locally. Consequently, British Commonwealth citizens were encouraged to come to Great Britain. In the Netherlands, the term African-Surinamese is used to refer to people with African ancestral origins and their offspring who migrated to the Netherlands from Suriname.14 African-Surinamese are mainly the descendants of West Africans who were taken to the Suriname during the slave trade era. The term Hindustani-Surinamese is used to refer to people with South-Asian ancestral origin, and their offspring who migrated to the Netherlands from Suriname. The Hindustani-Surinamese are the descendants of the indentured labourers from North India—Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal and West-Bihar. After the abolition of slavery in 1863, the emancipated Africans were unwilling to continue working on the plantations because of poor labour conditions. To guarantee a constant supply of labour, the planters imported indentured labourers from North India between 1873 and 1917. The migration of the African-Surinamese and Hindustani-Surinamese to the Netherlands was mainly due to the political situation in Suriname. There were two large migration waves. The first was around independence of Suriname in 1975 and the second wave was around the revolution coup of the Desi Bouterse in February 1980.15 White is the term most commonly accepted and used to describe people with European ancestral origins. For the purposes of this paper, based on populations in the Netherlands (Amsterdam) and England (National and Newcastle upon Tyne), we use the following terminology:

-

For England-based Indian → English-Indian

-

Dutch-based Hindustani Surinamese → Dutch-Indian

-

England-based African Caribbean → English-Caribbean

-

Dutch-based African Surinamese → Dutch-African

-

England-based people of English European origin → White-English

-

Dutch-based people of European origins → White-Dutch.

Appendix 2

Age-standardised prevalence of overweight/obesity by ethnic groups and sex. (BMI defined as ⩾25 kg in all groups)

Appendix 3

Age-standardised prevalence of overweight by ethnic groups and sex. BMI defined as ⩾23 kg in the South-Asian groups.

Appendix 4

Age-standardised prevalence of obesity by ethnic groups and sex.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agyemang, C., Kunst, A., Bhopal, R. et al. Dutch versus English advantage in the epidemic of central and generalised obesity is not shared by ethnic minority groups: comparative secondary analysis of cross-sectional data. Int J Obes 35, 1334–1346 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.281

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.281

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Type 2 diabetes burden among migrants in Europe: unravelling the causal pathways

Diabetologia (2021)

-

Overweight according to geographical origin and time spent in France: a cross sectional study in the Paris metropolitan area

BMC Public Health (2012)

-

How can we realise the potentially large public health benefit of screening for type 2 diabetes mellitus in south Asians?

Diabetologia (2011)