Abstract

We handle two major issues in applying extreme value analysis to financial time series, bias and serial dependence, jointly. This is achieved by studying bias correction methods when observations exhibit weak serial dependence, in the sense that they come from \(\beta\)-mixing series. For estimating the extreme value index, we propose an asymptotically unbiased estimator and prove its asymptotic normality under the \(\beta\)-mixing condition. The bias correction procedure and the dependence structure have a joint impact on the asymptotic variance of the estimator. Then we construct an asymptotically unbiased estimator of high quantiles. We apply the new method to estimate the value-at-risk of the daily return on the Dow Jones Industrial Average index.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In financial risk management, a key concern is on modelling and evaluating potential losses occurring with extremely low probabilities, i.e., tail risks. For example, the Basel committee on banking supervision suggests regulators to require banks holding adequate capital against the tail risk of bank assets measured by the value-at-risk (VaR). The VaR refers to a high quantile of the loss distribution with an extremely low tail probability.Footnote 1 Estimating such risk measures thus relies on modeling the tail region of distribution functions of asset values. To serve such a purpose, statistical tools stemming from extreme value theory (EVT) are obvious candidates. By investigating data in an intermediate region close to the tail, extreme value statistics employs models to extrapolate intermediate properties to the tail region. Although this attractive feature of extreme value statistics makes it a popular tool for evaluating tail events in many scientific fields such as meteorology and engineering, it has not yet emerged as a dominating tool in financial risk management. This is potentially due to some crucial critiques on applying EVT to financial data; see e.g. [4]. The critiques are mainly on two issues: the difficulty in selecting the intermediate region in estimation, and the validity for financial data of the maintained assumptions in EVT. This paper tries to deal with the two critiques simultaneously and provide adapted EVT methods that overcome the two issues jointly.

We start with explaining the problem on selecting the intermediate region in estimation. Extreme value statistics usually uses only observations in an intermediate region. This has been achieved by selecting the highest (or lowest, when dealing with the lower tail) \(k=k(n)\) observations in a sample with size \(n\). The problem of selecting \(k\) is sometimes referred to as “selecting the cutoff point”. Theoretically, the statistical properties of EVT-based estimators are established for \(k\) such that \(k\to\infty\) and \(k/n\to 0\) as \(n\to\infty\). In applications with a finite sample size, it is necessary to investigate how to choose the number of high observations used in estimation. For financial practitioners, two difficulties arise: firstly, there is no straightforward procedure for the selection; secondly, the performance of the EVT estimators is rather sensitive to this choice. More specifically, there is a bias–variance tradeoff: with a low level of \(k\), the estimation variance is at a high level which may not be acceptable for the application; by increasing \(k\), i.e., using progressively more data, the variance is reduced, but at the cost of an increasing bias.

Recent developments in extreme value statistics provide two types of solutions for selecting the cutoff point. The first aims to find the optimal cutoff point that balances the bias and variance assuming that the bias term in the asymptotic distribution is finite; see e.g. [3, 8] and [12]. The second type corrects the bias under allowing that the bias term in the asymptotic distribution is at an infinite level; see e.g. [10]. In comparison with the optimal cutoff point method, the bias correction procedure usually requires additional assumptions, such as a third order condition. Nevertheless, it is preferred to the optimal cutoff point approach because of the following relative advantages. First, since bias correction methods allow an infinite bias term in the asymptotic distribution, they correspondingly allow choosing a higher level of \(k\) than that chosen in the optimal cutoff point approach. Second, by choosing a larger \(k\), bias correction methods result in a lower level of estimation variance with no asymptotic bias. Third, in practice, bias correction procedures lead to estimates that are less sensitive to the choice of \(k\). This mitigates the difficulty in the selection of the cutoff point.

The other criticism on applying extreme value statistics to financial data is on the fact that most existing EVT methods require independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) observations, whereas financial time series exhibit obvious serial dependence features such as volatility clustering. This issue has been addressed in works dealing with weak serial dependence; see e.g. [15] and [5]. The main message from these studies is that usual EVT methods are still valid; only the asymptotic variance of estimators may differ from that in the i.i.d. case.

Since the selection of the cutoff point and the serial dependence in data have been handled separately, the literatures addressing these two issues are mutually exclusive. In the bias correction literature, it is always assumed that the observations form an i.i.d. sample; in the literature on dealing with serial dependence, the choice of \(k\) is assumed to be sufficiently low such that there is no asymptotic bias. Therefore, it is still an open question whether we can apply the bias correction technique to datasets that exhibit weak serial dependence. This is what we intend to address in this paper.

We consider a bias correction procedure on estimating the extreme value index and high quantiles for \(\beta\)-mixing stationary time series with common heavy-tailed distribution. The bias term stems from the approximation of the tail region of distribution functions. In EVT, a second order condition is often imposed to characterize such an approximation. Such a condition is almost indispensable for establishing asymptotic properties of estimators. To correct the bias, one needs to estimate the second order scale function, the function \(A\) in (2.3) below. The existing literature is restricted to the case \(A(t)=Ct^{\rho}\) with constants \(C\neq0\) and \(\rho<0\). The estimation of \(C\) requires extra conditions. Instead, we estimate the function \(A\) in a nonparametric way which makes the analysis and application smoother.

The asymptotically unbiased estimator we obtain has the following advantages. Firstly, it allows serial dependence in the observations. Secondly, one may apply the unbiased estimator with a higher value of \(k\), which reduces the asymptotic variance and ultimately the estimation error thanks to the bias correction feature. Thirdly, the theoretical range of potential choices of \(k\) is larger for our asymptotically unbiased estimators than for the original estimators. This makes the choice of \(k\) less crucial. All these features become apparent in simulation and application.

The paper is organized as follows. Under a simplified model without serial dependence, Sect. 2 presents the bias correction idea for the Hill estimator. Section 3 presents the general model with serial dependence, and in particular the regularity conditions we are dealing with. Section 4 defines the asymptotically unbiased estimators of the extreme value index and quantiles. In addition, we state the main theorems on the asymptotic normality of these two estimators. The bias correction procedure and the serial dependence structure have a joint impact on the asymptotic variances of the estimators. Section 5 discusses such a joint impact for several examples. Section 6 demonstrates finite sample performance of the asymptotically unbiased estimators based on simulation. An application to estimate the VaR of daily returns on the Dow Jones Industrial Average index is given in Sect. 7. All proofs are postponed to the Appendix.

2 The idea of bias correction under independence

For the sake of simplicity, we first introduce our bias correction idea under the assumption of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) observations in this section. We show later that our bias correction procedure also works for \(\beta\)-mixing series.

2.1 The origin of bias

Let \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) be an i.i.d. sequence of random variables with a common distribution function \(F\). We assume that this distribution function belongs to the domain of attraction with a positive extreme value index. We present the domain of attraction condition with respect to the quantile function \(U:=(1/(1-F))^{\leftarrow}\), where ← denotes the left-continuous inverse function. That is, there exists a positive number \(\gamma\) such that

Such a distribution function \(F\) is also called a heavy-tailed distribution. The relation (2.1) governs how a high quantile, say \(U(tx)\), can be extrapolated from an intermediate quantile \(U(t)\). Clearly, estimating the extreme value index \(\gamma\) is a major step in estimating high quantiles.

In the heavy-tailed case, [14] proposes for the parameter \(\gamma\) the estimator

where \(X_{1,n}\leq X_{2,n}\leq\cdots\leq X_{n,n}\) are the order statistics and \(k\) is an intermediate sequence such that \(k\to\infty\) and \(k/n\to0\) as \(n\to\infty\).

To obtain the asymptotic normality of the Hill estimator (and most other estimators in EVT), it is necessary to quantify the speed of convergence in (2.1). We thus assume a second order condition on the function \(U\) as follows. Suppose that there exist a positive or negative function \(A\) with \(\lim_{t\to\infty}A(t)=0\) and a real number \(\rho\leq0\) such that

for all \(x>0\). This is equivalent to

see for instance [13, Proof of Theorem 3.2.5]. The parameter \(\rho\) controls the speed of convergence, both of the sample maximum towards an extreme value distribution and for the extreme value estimators towards a normal distribution. Larger absolute values of \(\rho\) mean a better speed of convergence. This is illustrated in the last paragraph of Sect. 2.2.

The estimator \(\hat{\gamma}_{k}\) is consistent under the domain of attraction condition (2.1). Under the second order condition (2.3), the asymptotic normality can be established for i.i.d. observations as

if the intermediate sequence \((k_{\lambda})\) satisfies

where \(\lambda\) is a finite constant. This condition imposes an upper bound on the speed at which \(k_{\lambda}\) goes to infinity. The asymptotic bias for the Hill estimator is consequently given by the term \(\frac{\lambda}{1-\rho}\).

To obtain an asymptotically unbiased estimator, we first estimate the bias term and then subtract that from \(\hat{\gamma}_{k}\). The asymptotically unbiased estimator is then given as \(\hat{\gamma}_{k}-\widehat{{\mathrm{Bias}}_{k}}\), where

A formal definition of the asymptotically unbiased estimator is given in Eq. (4.2) below. It is clear that the second order parameter \(\rho\) plays an important role in the bias term.

2.2 Estimating the bias term

The estimation of the bias term requires estimating the second order parameter \(\rho\) and the second order scale function \(A\) appearing in the condition (2.3). The parameter \(\rho\) controls the speed of convergence of most \(\gamma\) estimators. In the following, we restrict the study to the case \(\rho<0\) because the estimation of the bias term exploits the regular variation feature of the function \(A\), whereas the case of slow variation (\(\rho=0\)) is difficult to handle. In the bias correction literature, in order to establish asymptotic properties of estimators of \(\rho\), it is necessary to choose a higher intermediate sequence \(k_{\rho}=k_{\rho}(n)\) such that \(k_{\rho}\to\infty\), \(k_{\rho}/n\to0\) and

as \(n\to\infty\); see e.g. [11]. This provides a lower bound to the speed at which \(k_{\rho}\) goes to infinity. Also, a third order condition is useful. Suppose that there exist a positive or negative function \(B\) with \(\lim_{t\to\infty }B(t)=0\) and a real number \(\rho^{\prime}\leq0\) such that

for all \(x>0\). If the observations are i.i.d., the asymptotic normality of all existing estimators of \(\rho\), including the one we use in (4.1) below, holds under the condition (2.6) and with a sequence \((k_{\rho})\) such that as \(n\to\infty\), \(k_{\rho}\to \infty\), \(k_{\rho}/n\to0\) and

where \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{2}\) are both finite constants; see for instance [11] and [2]. Here, since we are going to deal with \(\beta\)-mixing series, we need to re-establish the asymptotic property of the \(\rho\) estimator. The details are left to the Appendix.

In order to avoid extra bias stemming from the third order condition, the \(k\) sequence we use for the asymptotically unbiased estimator of the extreme value index is of a lower order, compared to the \(k_{\rho}\) sequence. More specifically, we use a sequence \((k_{n})\) such that as \(n\to\infty\), \(k_{n}\to\infty\), \(k_{n}/k_{\rho}\to0\) and

Comparing our asymptotically unbiased estimator with the original Hill estimator, the \(k\) sequences used for estimation are at different level. The conditions on \((k_{n})\) and \((k_{\lambda})\) imply that \(k_{n}/k_{\lambda}\to+\infty\) as \(n\to\infty\). Since the asymptotic variance of both the asymptotically unbiased estimator and the original Hill estimator is of an order \(1/k\), using a sequence \((k_{n})\) increasing faster than \((k_{\lambda})\) leads to a lower asymptotic variance of our asymptotic unbiased estimator compared to that of the original Hill estimator.

In addition, the \(k\) sequence used for the asymptotically unbiased estimator is more flexible in the following sense. The third order condition (2.6) implies that \(A\) and \(B\) are regularly varying functions with index \(\rho\) and \(\rho'\), respectively. Consider the special case that \(A(t)\sim Ct^{\rho}\) and \(B(t)\sim Dt^{\rho'}\) as \(t\to\infty\) for some constant \(C\) and \(D\). Then the condition that \(\sqrt{k_{\lambda}}A(n/k_{\lambda})\to\lambda\) restricts the level of \(k_{\lambda}\) as \(k_{\lambda}=O(n^{\frac{2\rho}{2\rho-1}})\), whereas condition (2.8) implies that \(k_{n}=O\left(n^{\tau}\right)\) for any \(\tau\in(\frac{2\rho}{2\rho-1},\frac{2(\rho+\max(\rho,\rho '))}{2(\rho+\max(\rho,\rho'))-1})\).

3 The serial dependence conditions

In this section, we present the serial dependence conditions on the time series we are going to deal with. The serial dependence structure follows from the so-called \(\beta\)-mixing conditions. The \(\beta\)-mixing conditions have been introduced by [19, 5, 7] and [20] as follows. Let \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) be a stationary time series with common distribution function \(F\). Let \(\mathcal{B}_{i}^{j}\) denote the \(\sigma\)-algebra generated by \(X_{i},\ldots,X_{j}\). The sequence is said to be \(\beta\)-mixing or absolutely regular if

as \(m\to\infty\). The constants \(\beta(m)\) are called the \(\beta \)-mixing constants of the sequence.

The asymptotic normality of the original Hill estimator has been established for \(\beta\)-mixing sequences in [5, 7] with some mild extra conditions. With a sequence \((k_{\lambda})\) such that \(\sqrt{k_{\lambda}}A(n/k_{\lambda})\to \lambda\) as \(n\to\infty\), it is proved that

where \(\sigma^{2}\) is equal to \(\gamma^{2}\) under independence but is more complicated otherwise. The extra conditions for establishing the asymptotic normality of the Hill estimator are the following list of regularity conditions. Suppose there exist a constant \(\varepsilon>0\), a function \(r(\cdot,\cdot)\) and a sequence \(\ell =(\ell_{n})\) such that as \(n\to\infty\),

-

(a)

\(\frac{\beta(\ell)}{\ell}n+\ell k^{-1/2}\log^{2}k \to0\);

-

(b)

\(\frac{n}{\ell k}{\mathrm{Cov}}(\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}{\mathbf{1}}_{\{ X_{i}>F^{-1}(1-kx/n)\}}, \sum_{i=1}^{\ell}{\mathbf{1}}_{\{X_{i}>F^{-1}(1-k y/n)\}})\to r(x,y)\), for any \(0\leq x,y\leq1+\varepsilon\);

-

(c)

For some constant \(C\),

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{n}{\ell k}\mathbb{E}\Bigg[\bigg(\sum_{i=1}^{\ell}{\mathbf{1}}_{\{ F^{-1}(1-k y/n)< X_{i}\leq F^{-1}(1-k x/n)\}}\bigg)^{4}\Bigg]\leq C(y-x), \end{aligned}$$for any \(0\leq x< y\leq1+\varepsilon\) and \(n\in\mathbb{N}\).

Drees [5] shows that the condition (a) is fulfilled if the original time series \((X_{1},X_{2},\dots)\) is geometrically \(\beta \)-mixing, i.e., \(\beta(m)=O(\eta^{m})\) for some \(\eta\in(0,1)\). In that case, one may take \(\ell_{n}=[-2\log n/\log\eta]\). In [7], Drees remarks that the condition (b) holds if all vectors \((X_{1},X_{1+m})\) belong to the domain of attraction of a bivariate extreme value distribution. In that case, for any sequence \(k\), one may take a sequence \(\ell\) such that \(\ell k/n\to0\) as \(n\to\infty\). The limit function \(r(x,y)\) depends only on the tail dependence structure of \((X_{1},X_{1+m})\) for \(m\in\mathbb{N}\). These two sufficient versions of conditions (a) and (b) hold for some known time series models, namely the ARMA, ARCH and GARCH models; see the examples in Sect. 5 below. Lastly, the condition (c) has been verified for these time series models as well. In addition, for all these models, it is only necessary to have \(k=o(n^{\zeta})\) for some \(\zeta<1\) as \(n\to\infty\) in order to satisfy the regularity conditions. This is compatible with the requirement on the sequence \((k_{\lambda})\) in extreme value analysis as follows. Under the second order condition, \(\left\vert A(t)\right\vert\) is regularly varying with index \(\rho\). Therefore, given any \(\varepsilon>0\), for sufficiently large \(t\), we have that \(\left\vert A(t)\right\vert >Ct^{\rho-\varepsilon}\) for some positive constant \(C\); see inequality (B.1.19) in [13]. Together with the condition (2.4), we get that \(k_{\lambda}=o(n^{\zeta})\) for any \(\zeta>\frac{2\rho-\varepsilon}{2\rho-1-\varepsilon}\). Therefore, the sequence \((k_{\lambda})\) is compatible with condition (c).

We intend to correct the bias while allowing the observations to follow the \(\beta\)-mixing condition and the regularity conditions. Since the asymptotic bias of the original Hill estimator under serial dependence has the same form as in (2.5), we can construct an asymptotically unbiased estimator for \(\beta\)-mixing sequences with exactly the same form as in the case of independence. Nevertheless, due to the serial dependence, the asymptotic property of the estimator has to be re-established. This is what we do in the next section.

4 Main results

We start by introducing the estimator of the second order parameter. Then we state our main results on the asymptotic properties of the asymptotic unbiased estimators of the extreme value index and high quantiles.

4.1 Estimating the second order parameter

We adopt the notations of [11] as follows. For any positive number \(\alpha\), denote

Then the estimator of the second order parameter \(\rho\) is defined as

4.2 Asymptotically unbiased estimator of the extreme value index

We now write explicitly the asymptotically unbiased estimator of the extreme value index. Let \(k_{\rho}\) and \(k_{n}\), satisfying (2.7) and (2.8), be the number of observations selected for estimating \(\rho\) and \(\gamma\), respectively. For some positive real number \(\alpha\), we define the asymptotically unbiased estimator as

where \(\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n}}\) denotes the original Hill estimator as in (2.2).

The following theorem shows the asymptotic normality of our asymptotically unbiased estimator for \(\beta\)-mixing series. The consistency of the estimator could be obtained under the second order condition without requiring the third order condition.

Theorem 4.1

Suppose that \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) is a stationary \(\beta\)-mixing time series with continuous common marginal distribution function \(F\). Assume that \(F\) satisfies the third order condition (2.6) with parameters \(\gamma>0\), \(\rho<0\) and \(\rho^{\prime}\leq0\). Suppose that the two intermediate sequences \((k_{\rho})\) and \((k_{n})\) satisfy the conditions in (2.7) and (2.8), respectively. Suppose that the regularity conditions (a)–(c) hold with the intermediate sequence \((k_{n})\). Then

where

with

and \(r(\cdot,\cdot)\) defined in the regularity condition (b).

Compared to the original Hill estimator, we use different \(k\) sequences, namely \((k_{n})\) and \((k_{\rho})\), in the asymptotically unbiased estimator \(\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n},k_{\rho},\alpha}\). These \(k\) sequences are compatible with the regularity conditions. Recall that the third order condition (2.6) implies that \(A^{2}\) and \(AB\) are regularly varying functions with index \(2\rho\) and \(\rho+\rho'\), respectively. Conditions (2.7) and (2.8) ensure that \(k_{n},k_{\rho}\) are \(o(n^{\zeta})\) for some \(\zeta<1\) and consequently yield the compatibility of these two sequences with the regularity conditions. In general, as long as the original sequence \((k_{\lambda})\) is compatible with the regularity conditions, so are \((k_{n})\) and \((k_{\rho})\).

We remark that our estimator is also valid as an asymptotically unbiased estimator of the extreme value index when the observations are i.i.d. In that case, the result is simplified to

4.3 Asymptotically unbiased estimator of high quantiles

We consider the estimation of high quantiles. High quantile here refers to the quantile at a probability level \(1-p\), where the tail probability \(p=p_{n}\) depends on the sample size \(n\): as \(n\to \infty\), \(p_{n}=O(1/n)\). The goal is to estimate the quantile \(x(p)=U(1/p)\). In extreme cases such that \(np_{n}<1\), it is not possible to have a nonparametric estimate of such a quantile.

We propose the asymptotically unbiased estimator

The first factor \(X_{n-k_{n},n}(\frac{k_{n}}{np})^{\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n},k_{\rho},\alpha}}\) in this formula follows a similar structure as the quantile estimator in [23]. Having the additional term is to correct the extra bias induced by using a high level \(k_{n}\); see a similar treatment in [1] for the quantile estimator using an asymptotically unbiased probability-weighted moment approach.

The following theorem shows the asymptotic normality of the quantile estimator \(\hat{x}_{k_{n},k_{\rho},\alpha}(p)\).

Theorem 4.2

Suppose that \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) is a stationary \(\beta\)-mixing time series with continuous common marginal distribution function \(F\). Assume that \(F\) satisfies the third order condition (2.6) with parameters \(\gamma>0\), \(\rho<0\) and \(\rho^{\prime}\leq0\). Suppose that the two intermediate sequences \((k_{\rho})\) and \((k_{n})\) satisfy the conditions in (2.7) and (2.8), respectively. Assume in addition that \(n\to\infty\), \(np_{n}/k_{n}\to0\) and \(\log(np_{n})/\sqrt {k_{n}}\to0\). Suppose that the regularity conditions (a)–(c) hold with \((k_{n})\). Then

with \(\sigma^{2}\) as defined in Theorem 4.1.

5 Examples

In our framework, we model the serial dependence by the \(\beta\)-mixing condition and the extra regularity conditions. In this section, we give a few examples that satisfy those conditions. The studies referred to below have documented that these examples satisfy the regularity conditions for any sequence \(k\) such that \(k=o(n^{\zeta})\) for some \(\zeta<1\) as \(n\to\infty\).

-

The \(k\)-dependent process and the autoregressive (AR) process AR(1); see [19, 7, 20].

-

The AR(\(p\)) processes and the infinite moving averages (MA) processes; see [18, 6].

-

The autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity process ARCH(1); see [6, 7].

-

The generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) processes; see [21, 5].

We review some simple cases of these processes and provide a comparison of the asymptotic variance under dependence to that under independence, and to that of the original Hill estimator under serial dependence.

5.1 Autoregressive model

Consider first the stationary solution of the AR(1) equation

for some \(\theta\in(0,1)\) and i.i.d. random variables \(Z_{i}\). The distribution function of the innovations is denoted by \(F_{Z}\). Assume that \(F_{Z}\) admits a positive Lebesgue density which is \(L_{1}\) Lipschitz-continuous; see [7, Eq. (42)]. Suppose that as \(x\to\infty\),

for some slowly varying function \(\ell\) and \(p=1-q\in(0,1)\). Then from Sect. 3.2 of [7], we get that \(1-F(x)\sim d_{\theta}\left(1-F_{Z}(x)\right)\) as \(x\to\infty\), where \(d_{\theta}=(1-\theta ^{1/\gamma})^{-1}\). Furthermore, the regularity conditions hold with

where \(c_{m}(x,y)=x\wedge y\theta^{m/\gamma}\).

Let us denote by \(\sigma^{2}(\theta,\gamma,\rho)\) the asymptotic variance of \(\sqrt{k}(\hat{\gamma}_{k,k_{\rho},\alpha} -\gamma)\). First, we compare the asymptotic variance under model (5.1) with that under independence by calculating the ratio \(\sigma^{2}(\theta ,\gamma,\rho)/\sigma^{2}(0,\gamma,\rho)\). Second, we compare \(\sigma ^{2}(\theta,\gamma,\rho)\) with the asymptotic variance \(\sigma_{H}^{2}\) of the original Hill estimator under serial dependence when using the same \(k\) sequence. From [5], we get that under serial dependence, \(\sqrt{k}(\hat{\gamma}_{H}-\gamma)\) converges to a normal distribution with asymptotic variance \(\sigma_{H}^{2}=\gamma^{2}r(1,1)\). The two ratios are given by

In the first row of Fig. 1, we plot these ratios against the extreme value index \(\gamma\) for different values of the parameters \(\theta\) and \(\rho\). From Fig. 1(a), we note that the variation of the first ratio is mainly due to that of \(\theta \). The parameter \(\rho\) plays a relatively minor role. We further give a numerical illustration with \(\gamma=1\) and \(\rho=-1\). With i.i.d. observations, the asymptotic variance of \(\sqrt{k}(\hat{\gamma }_{k,k_{\rho},\alpha} -\gamma)\) is 5. Instead, if the observations follow the AR(1) model with \(\theta=0.5\), then the asymptotic variance of \(\sqrt{k}(\hat{\gamma}_{k,k_{\rho},\alpha} -\gamma)\) is close to 20. Hence, overlooking the serial dependence may severely underestimate the range of confidence intervals.

Differently, we observe from Fig. 1(b) that the variation of the second ratio is mainly due to that of \(\rho\). Although this ratio is greater than one, it does not imply that the asymptotically unbiased estimator has a higher asymptotic variance because the current comparison is conducted using the same \(k\) level for both estimators, whereas the \(k\) value used in the asymptotically unbiased estimator can be at a much higher level than that used for the Hill estimator. Theoretically, the conditions on \((k_{n})\) and \((k_{\lambda})\) guarantee that \(k_{n}/k_{\lambda}\to+\infty\). Thus the variance of our estimator is at a lower level asymptotically. Practically, if we consider the example \(\rho=-1\), then the ratio is between 5 and 7. Under such an example, if we use in the asymptotically unbiased estimator a \(k_{n}\) seven times higher than \(k_{\lambda}\) used for the original Hill estimator, we get an estimator with lower variance. If the level of \(\rho\) is closer to zero, then the ratio will be at a higher level. Correspondingly, one needs a higher level of \(k_{n}\) to offset the higher ratio. Nevertheless, together with the fact that the asymptotically unbiased estimator does not suffer from the bias issue, it may still perform better in terms of having a lower root mean squared error. Such a feature will show up in the simulation studies in Sect. 6 below.

5.2 Moving average model

Consider now the stationary solution of the MA(1) equation

where the innovation \(Z\) satisfies the same conditions as in the AR(1) model in the previous subsection. Again from Sect. 3.2 of [7], we get that \(1-F(x)\sim d_{\theta}\left(1-F_{Z}(x)\right)\) as \(x\to\infty\), where \(d_{\theta}=1+\theta^{1/\gamma}\). One can also compute

We calculate the two ratios when comparing the asymptotic variance of the asymptotically unbiased estimator under serial dependence to that under independence, and that of the original Hill estimator under dependence as

In the second row of Fig. 1, we plot the variations of these ratios with respect to the extreme value index \(\gamma\) for different values of the parameters \(\theta\) and \(\rho\). The general feature is comparable to that observed from the first row. A notable difference between Figs. 1(a) and 1(c) is that although the ratios are both increasing in \(\theta\) and the absolute value of \(\rho\), their convexities with respect to \(\gamma\) are different in the two models: we observe a concave (resp., convex) relation in \(\gamma\) under the MA(1) (resp., AR(1)) model.

5.3 Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model

Consider the stationary solution to the recursive system of equations

where the \(\varepsilon_{t}\) are i.i.d. innovations with zero mean and unit variance. The stationary solution \(X_{t}\) of this \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model follows a heavy-tailed distribution, even if the innovations \(\varepsilon_{t}\) are normally distributed; see [16] and [9]. The extreme value index of the \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model can be derived from the Kesten theorem on stochastic difference equations; see [16]. Nevertheless, the calculation is not explicit.

In addition, the stationary \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) series satisfies the \(\beta \)-mixing condition and the regularity conditions; see [21] and [5]. Thus, it can be considered as an example for which we can apply the asymptotically unbiased estimators. Since it is difficult to explicitly calculate the \(r(\cdot,\cdot)\) function and consequently the asymptotic variance, we opt to use simulations to show the performance of the asymptotically unbiased estimator under the GARCH model.

6 Simulation

6.1 Data generating processes

The simulations are set up as follows. We consider four data generating processes for simulating the observations used in our simulation study. Suppose \(Z\) follows the distribution \(F_{Z}\) given by

where \(\tilde{F}\) is the standard Fréchet distribution function, \(\tilde{F}(x)=\exp(-1/x)\) for \(x>0\), and \(p=0.75\). Then \(F_{Z}\) belongs to the domain of attraction with extreme value index 1. We construct three time series models based on i.i.d. observations \(Z_{t}\) as follows:

-

Model 1. Independence: \(X_{t}=Z_{t}\) (can be regarded as MA(1) with \(\theta=0\));

-

Model 2. AR(1): \(X_{t}\) given by (5.1) with \(\theta=0.3\);

-

Model 3. MA(1): \(X_{t}\) given by (5.2) with \(\theta=0.3\).

In all three models, the theoretical value of \(\gamma\) is 1. In addition, we also construct a \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model as in Sect. 5.3. We remark that the heavy-tailed feature of the \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model does not depend on whether the innovations follow a heavy-tailed distribution. Nevertheless, empirical evidence supports using heavy-tailed innovations for modeling financial time series; see e.g. [17] and [22]. Correspondingly, we use the Student-\(t\) distribution as the distribution of innovations.Footnote 2 All parameters in the simulated \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model are equal to the estimates from the real data application in Sect. 7.

-

Model 4. \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\): \(X_{t}\) given as in Sect. 5.3 with \(\lambda_{0}=8.26\times10^{-7}\), \(\lambda_{1}=0.052\), \(\lambda _{2}=0.941\). The innovation term follows the standardized Student-\(t\) distribution with degree of freedom \(\nu=5.64\).

Following [16], we calculate the extreme value index \(\gamma\) of the series in Model 4 as 0.258.

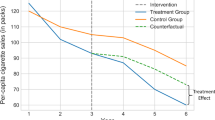

In our simulation study, we also compare the performance of our asymptotically unbiased quantile estimator to that of the original Weissman [23] estimator. For that purpose, we estimate \(x(0.001)\) for simulated samples from the four data generating processes. We conduct pre-simulations to get the theoretical values of \(x(0.001)\); for each model, we simulate 500 samples with sample size \(10^{6}\) and obtain 500 estimations of \(x(0.001)\). Table 1 reports the median of these 500 values for each model.

6.2 Estimation procedure

For each data generating process, we simulate \(N=1000\) samples with sample size \(n=1000\) each. First, we focus on the extreme value index \(\gamma\). We apply both the original Hill estimator and the asymptotically unbiased estimator in (4.2) to each sample. To apply the asymptotically unbiased estimator, we use the following procedure.

-

Estimate the second order index \(\rho\) by (4.1) with \(\alpha=2\).

-

Denote by \(m\) the number of positive observations in the sample. For each \(k\) satisfying \(k\leq\min(m-1,\frac{2m}{\log\log m})\), calculate the statistic

$$\begin{aligned} S_{k}^{(2)}=\frac{3}{4}\frac{(M_{k}^{(4)}- 24 (M_{k}^{(1)})^{4}) (M_{k}^{(2)}-2(M_{k}^{(1)})^{2})}{M_{k}^{(3)}-6 (M_{k}^{(1)})^{3}}. \end{aligned}$$ -

If \(S_{k}^{(2)}\in[2/3,3/4]\), then let

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\rho}_{k}=\frac{-4+6 S_{k}^{(2)}+\sqrt{3 S_{k}^{(2)}-2}}{4 S_{k}^{(2)}-3}. \end{aligned}$$ -

If \(S_{k}^{(2)}<2/3\) or \(S_{k}^{(2)}>3/4\), then \(\hat{\rho }_{k}\) does not exist.

-

The parameter \(\rho\) is estimated as \(\hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}\) with

$$\begin{aligned} k_{\rho}=\sup\bigg\{ k:k\leq\min\left(m-1,\frac{2m}{\log\log m}\right) \ \mbox{and } \hat{\rho}_{k} {\mbox{ exists}}\bigg\} . \end{aligned}$$

-

-

Estimate the extreme value index by (4.2) for various values of \(k_{n}\),Footnote 3 using \(\hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}\).

Here the choice of \(k_{\rho}\) in the first step follows the recommendation in [11].

Next, we estimate the high quantile \(x(0.001)\) by both the original Weissman estimator and the asymptotically unbiased estimator as in Sect. 4.3. When applying the asymptotically unbiased estimator for high quantiles, we use the same \(\hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}\) as above.

Once we have obtained the estimates in the \(N=1000\) samples as \(\hat{\gamma}_{k}^{(j)}\) for \(j=1,2,\dots,N\), we calculate the average absolute bias (ABias) and the root mean square error (RMSE) for the two extreme value index estimators by

Then we plot the results against the corresponding \(k\) values in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 for each model, respectively.

Similarly, we obtain the ABias and RMSE for the two high quantile estimators. The ABias and RMSE for the four models are plotted in Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, respectively.

6.3 Results

Regarding the estimation of the extreme value index, we observe that even with a rather high level of \(k\), our asymptotically unbiased estimator does not suffer from a significant bias, at least for the first three models; see Figs. 2–4. In Model 4, the bias term increases with respect to \(k\), but still stays at a lower level than that of the original Hill estimator; see Fig. 5. In addition, we compare the reduction of RMSE when switching from the original Hill estimator to the asymptotically unbiased estimator. Across the first three models, the best levels of RMSE are reached for the largest values of \(k\). In Model 4, the RMSE has a different pattern as \(k\) increases. However, the reduction is the most significant in Model 4. Although the lowest achieved RMSE for the asymptotically unbiased estimator is at a comparable level as the lowest RMSE for the original Hill estimator for Models 2 and 3, the decrease of the RMSE with respect to \(k\) demonstrated by the asymptotically unbiased estimator allows a more flexible choice of \(k\) compared to the U-shaped RMSE demonstrated by the original Hill estimator.

Regarding the estimation of high quantiles, we observe from Figs. 6–9 that our goal in reducing the bias is well illustrated on a finite sample when using large \(k\) values. In addition, the RMSE of our asymptotically unbiased quantile estimator stays at a lower level than that of the original Weissman estimator for high levels of \(k\). It is remarkable that the reduction in RMSE is higher for dependent series than for independent series.

To conclude, the simulation studies show that under bias correction, the estimators for extreme value index and high quantiles remain stable for a wider range of \(k\) values even if the dataset exhibits serial dependence. The bias correction method under serial dependence thus helps to tackle the two major critiques for applying extreme value statistics to financial time series.

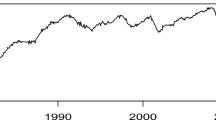

7 Application

We apply the asymptotically unbiased estimators on the extreme value index and high quantiles to evaluate the downside tail risk in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) index. We collect the daily index from 1980 to 2010 and compute the daily loss returns. The indices and loss returns are presented in Figs. 10(a) and 10(b). From the figures, we observe that although the loss return series can be regarded as stationary, there is evidence of serial dependence such as volatility clustering. More concretely, by fitting the \(\mbox{GARCH}(1,1)\) model with Student-\(t\) distributed innovations to our dataset, we obtain estimates as \(\hat{\lambda}_{0}=8.26\times10^{-7}\), \(\hat{\lambda}_{1}=0.052\), \(\hat{\lambda}_{2}=0.941\) and \(\hat{\nu}=5.64\). The existence of serial dependence prevents us from treating the series as i.i.d. observations. The serial dependence has to be accounted for when performing extreme value analysis.

Our goal is to estimate the value-at-risk of the return series at the \(99.9~\%\) level, which corresponds to a high quantile with tail probability \(0.1~\%\), i.e., \(x(0.001)\). From 8088 daily observations, a nonparametric estimate can be obtained by taking the eighth highest order statistic. We thus get \(7.16~\%\) as the empirical estimate.

Next, we apply both the original Hill estimator and the asymptotically unbiased estimator to estimate the extreme value index of the loss return series. We start with estimating the second order parameter \(\rho\). Following the estimation procedure in Sect. 6.2, we choose \(k_{\rho}=3515\) and obtain that \(\hat{\rho}=-0.611\). Next we apply both estimators for \(k_{n}=50,51,\dots,2000\). Since we do not employ a parametric model for the time series, there is no explicit formula for calculating the asymptotic variance of the two estimators. Therefore, we opt to use a block bootstrapping method to construct the confidence interval for the extreme value index.

The block bootstrapping follows the routine tsboot in the package boot in R. The block lengths are chosen to have a geometric distribution (sim=geom) with mean l=200. By repeating such a bootstrapping procedure 50 times, we obtain 50 bootstrapped estimates for each estimator. The sample standard deviation across the 50 estimates gives an estimate of the standard deviation of the underlying estimator for given \(k_{n}\). We construct the 95 % confidence interval using the point estimate and the estimated standard deviation. This procedure is applied to all values of \(k_{n}\) and for both estimators. The point estimates of the extreme value index as well as the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are plotted against different choices of \(k_{n}\) in Fig. 11.

Lastly, we apply both the original Weissman estimator and the asymptotically unbiased version to estimate the VaR at \(99.9~\%\) level. The construction of the confidence intervals follows a similar block bootstrapping procedure. The results are plotted in Fig. 12.

From the two figures, we observe that the estimates using the bias correction technique stay stable for a larger range of \(k\) values. In contrast, the estimates based on the original Hill estimator suffer from a large bias starting from \(k\geq400\). When applying the original EVT estimators, it is possible to choose \(k\) only around 250, which corresponds to \(3~\%\) of the total sample. Correspondingly, we obtain an estimated extreme value index at 0.349 from the Hill estimator and an estimated VaR at 0.06549 from the Weissman estimator. With our asymptotically unbiased estimators, we can take \(k=1000\) and obtain an estimated extreme value index at 0.280 with an estimated VaR at 0.05898. Note that the point estimates of the VaR are below, but close to, the empirical estimate. In addition to the point estimation, we investigate the confidence intervals of the estimated VaR. The Weissman estimator results in a 95 % confidence interval as \([0.04268, 0.08831]\), while the confidence interval obtained from our asymptotically unbiased estimator is \([0.04219,0.07577]\). Hence we conclude that the bias correction procedure helps to obtain a more accurate estimate with a narrower confidence interval.

Notes

In the revised Basel II accord and the subsequent Basel III accord, the VaR measures for risks on both trading and banking books must be calculated at a 99.9 % level.

In order to get a unit variance, we simply normalize the standard Student-\(t\) distribution with degree of freedom \(\nu\) by its standard deviation \(\sqrt{\nu/(\nu-2)}\).

For Models 1–3, we use \(k_{n}=10,11,\ldots, 700\), while for Model 4, we use \(k_{n}=10,11,\ldots, 450\) due to a lower number of positive observations.

References

Cai, J.-J., de Haan, L., Zhou, C.: Bias correction in extreme value statistics with index around zero. Extremes 16, 173–201 (2013)

Ciuperca, G., Mercadier, C.: Semi-parametric estimation for heavy tailed distributions. Extremes 13, 55–87 (2010)

Danielsson, J., de Haan, L., Peng, L., de Vries, C.G.: Using a bootstrap method to choose the sample fraction in tail index estimation. J. Multivar. Anal. 76, 226–248 (2001)

Diebold, F., Schuermann, T., Stroughair, J.: Pitfalls and opportunities in the use of extreme value theory in risk management. J. Risk Finance 1(2), 30–35 (2000)

Drees, H.: Weighted approximations of tail processes for \(\beta \)-mixing random variables. Ann. Appl. Probab. 10, 1274–1301 (2000)

Drees, H.: Tail empirical processes under mixing conditions. In: Dehling, H., et al. (eds.) Empirical Process Techniques for Dependent Data, pp. 325–342. Birkhäuser Boston, Boston (2002)

Drees, H.: Extreme quantile estimation for dependent data, with applications to finance. Bernoulli 9, 617–657 (2003)

Drees, H., Kaufmann, E.: Selecting the optimal sample fraction in univariate extreme value estimation. In: Stochastic Processes and their Applications, vol. 75, pp. 149–172 (1998)

Goldie, C.M.: Implicit renewal theory and tails of solutions of random equations. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1, 126–166 (1991)

Gomes, M.I., de Haan, L., Rodrigues, L.: Tail index estimation for heavy-tailed models: accommodation of bias in weighted log-excesses. J. R. Stat. Soc., Ser. B, Stat. Methodol. 70, 31–52 (2008)

Gomes, M.I., de Haan, L., Peng, L.: Semi-parametric estimation of the second order parameter in statistics of extremes. Extremes 5, 387–414 (2002)

Guillou, A., Hall, P.: A diagnostic for selecting the threshold in extreme value analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc., Ser. B, Stat. Methodol. 63, 293–305 (2001)

de Haan, L., Ferreira, A.: Extreme Value Theory. An Introduction. Springer Series in Operations Research and Financial Engineering. Springer, New York (2006)

Hill, B.: A simple general approach to inference about the tail of a distribution. Ann. Stat. 3, 1163–1174 (1975)

Hsing, T.: On tail index estimation using dependent data. Ann. Stat. 19, 1547–1569 (1991)

Kesten, H.: Random difference equations and renewal theory for products of random matrices. Acta Math. 131, 207–248 (1973)

McNeil, A.J., Frey, R.: Estimation of tail-related risk measures for heteroscedastic financial time series: an extreme value approach. J. Empir. Finance 7, 271–300 (2000)

Resnick, S., Stărică, C.: Asymptotic behavior of Hill’s estimator for autoregressive data. Commun. Stat., Stoch. Models 13, 703–721 (1997)

Rootzén, H.: The tail empirical process for stationary sequence. Preprint (1995). Chalmers Univ. Gothenburg. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.52.4828

Rootzén, H.: Weak convergence of the tail empirical process for dependent sequences. Stoch. Process. Appl. 119, 468–490 (2009)

Stărică, C.: On the tail empirical process of solutions of stochastic difference equations. Preprint (1999). Chalmers Univ. Gothenburg. Available online at: http://143.248.27.21/mathnet/paper_file//Chalmers/Catalin/aarch.pdf

Sun, P., Zhou, C.: Diagnosing the distribution of GARCH innovations. J. Empir. Finance 29, 287–303 (2014)

Weissman, I.: Estimation of parameters and large quantiles based on the \(k\) largest observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 73, 812–815 (1978)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees and the Associate Editor for their helpful comments. Laurens de Haan’s research was partially supported by ENES project EXPL/MAT-STA/0622/2013. Cécile Mercadier and Chen Zhou’s research was partially supported by the EUR-fellowship grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Proofs

Appendix: Proofs

The asymptotically unbiased estimator of the extreme value index is based on the sample moments

defined in Sect. 4.1. One can write these statistics as functionals of the tail quantile process \((Q_{n}(t):=X_{n-[kt],n})_{t\in [0,1]}\) via

Therefore, to derive the asymptotic properties of the asymptotically unbiased estimator, we first establish those of the tail quantile process and the moments. We first show that the tail quantile process can be approximated by a Gaussian process as in the following result.

Proposition A.1

Suppose that \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) is a stationary \(\beta\)-mixing time series with continuous common marginal distribution function \(F\). Assume that \(F\) satisfies the third order condition (2.6) with parameters \(\gamma>0\), \(\rho<0\) and \(\rho^{\prime}\leq0\). Suppose that an intermediate sequence \(k\) satisfies, as \(n\to\infty\), that \(k\to\infty\), \(k/n\to0\) and \(\sqrt{k}A(n/k)B(n/k)=O(1)\). In addition, assume that the regularity conditions (a)–(c) hold. Then, for a given \(\varepsilon>0\), under a Skorohod construction, there exist two functions \(\tilde{A}\sim A\) and \(\tilde{B}=O(B)\), where \(A\) and \(B\) are the second and third order scale functions in (2.6), and a centered Gaussian process \((e(t))_{t\in[0,1]}\) with covariance function \(r\) defined as in the regularity condition (b) such that, as \(n\to\infty\),

Proof

By writing \(X_{i}=U(Y_{i})\) where each \(Y_{i}\) follows a standard Pareto distribution, we obtain that \((Y_{1},Y_{2},\dots)\) is a stationary \(\beta \)-mixing series satisfying the regularity conditions. This is a direct consequence of \(Y_{i}=1/(1-F(X_{i}))\). We write \(Q_{n}(t)=X_{n-[kt],n}=U(Y_{n-[kt],n})\) and focus first on the asymptotic properties of the process \((Y_{n-[kt],n})_{t\in[0,1]}\). By verifying the conditions in Drees [7, Theorem 2.1], we get that under a Skorohod construction, there exists a centered Gaussian process \((e(t))_{t\in[0,1]}\) with covariance function \(r\) defined in the regularity condition (b) such that for \(\varepsilon>0\), as \(n\to\infty\),

Next, we present an inequality on the function \(U\) based on the third order condition (2.6). Under that condition, there exist two functions \(\tilde{A}\sim A\) and \(\tilde{B}=O(B)\) such that for any \(\delta>0\), there exists some positive number \(u_{0}(\delta)\) such that for all \(u\geq u_{0}\) and \(ux\geq u_{0}\),

This inequality is a direct consequence of applying de Haan and Ferreira [13, Theorem B.3.10] to the function \(f(u)=\log U(u)-\gamma\log u\).

We combine the asymptotic property of \((Y_{n-[kt],n})_{t\in[0,1]}\) in (A.1) with the inequality (A.2) as follows. Taking \(u=n/k\) and \(ux=Y_{n-[kt],n}\) in (A.2), we get that given any \(0<\delta<-\rho-\rho^{\prime}\), for sufficiently large \(n>n_{0}(\delta )\), with probability 1,

By applying (A.1), we bound the four terms in (A.3) that contain \(\frac{k_{n}}{n}Y_{n-[k_{n}t],n}\) to get

When taking \(n\to\infty\), with the facts that \(\sup_{t\in (0,1]}t^{1/2+\varepsilon}t^{-1}\left\vert e(t)\right\vert =O(1) \ \mbox{a.s.}\), \(\sqrt{k}\tilde{A}(n/k)\tilde{B}(n/k)=O(1)\) and \(\tilde{A}(n/k), \tilde{B}(n/k)\to0\), the proposition is proved due to the arbitrary choice of \(\delta\). □

By applying Proposition A.1, we get the asymptotic properties of the moments \(M_{k}^{(\alpha)}\) as follows.

Corollary A.2

Assume that the conditions in Proposition A.1 hold. Then under the same Skorohod construction as in Proposition A.1, as \(n\to\infty\),

where the \(P_{1}^{(\alpha)}\) are normally distributed random variables with mean zero. In addition,

with the covariance function \(r\) defined as in the regularity condition (b).

Proof of Corollary A.2

Recall that

Under the same Skorohod construction as in Proposition A.1, we get that as \(n\to\infty\),

The second order expansion \((1+x)^{\alpha}=1+\alpha x+\frac{\alpha (\alpha-1)}{2}x^{2}+o(x^{2})\) yields that as \(n\to\infty\),

Some terms are omitted because we have \(\sup_{t\in (0,1]}t^{1/2+\varepsilon}t^{-1}\left\vert e(t)\right\vert=O(1)\; \mbox{a.s.}\) and \(\tilde{A}(n/k)\to0\) as \(n\to\infty\).

By taking \(\varepsilon<1/2\), we can then take the integral of \((\log \frac{Q_{n}(t)}{ Q_{n}(1)})^{\alpha}\) on \((0,1]\) and use the fact that \(\int_{0}^{1}(-\log t)^{a-1} t^{-b} dt=\frac{\Gamma(a)}{(1-b)^{a}}\) for \(b<1\) to obtain the result in the corollary. The random term is \(P_{1}^{(\alpha)}=\int_{0}^{1}(-\log t)^{\alpha-1} (t^{-1}e(t)-e(1))\,dt\). The covariance can be calculated from there. □

Next, we handle the estimator of the second order parameter \(\rho\). The estimator of \(\rho\) is based on a different sequence \((k_{\rho})\) satisfying (2.7). Because \((k_{\rho})\) satisfies the condition in Proposition A.1, we get the asymptotic properties of the moments \(M_{k_{\rho}}^{(\alpha)}\) as in Corollary A.2. Then, following the same lines as in the proof of Gomes et al. [11, Theorem 2.2], we get the following result.

Proposition A.3

Suppose that \((X_{1}, X_{2}, \ldots)\) is a stationary \(\beta\)-mixing time series with continuous common marginal distribution function \(F\). Assume that \(F\) satisfies the third order condition (2.6) with parameters \(\gamma>0\), \(\rho<0, \rho^{\prime}\leq0\). Suppose that an intermediate sequence \((k_{\rho})\) satisfies (2.7). In addition, assume that the regularity conditions hold. Then for the \(\rho\)-estimator defined in (4.1) and as \(n\to\infty\),

is asymptotically normally distributed.

We remark that analogously to the result in Theorem 2.1 in Gomes et al. [11], the consistency of the \(\rho\)-estimator for \(\beta\)-mixing time series can be proved under only the second order condition (2.3) and weaker conditions on \((k_{\rho})\).

Finally, we can use the tools built in Corollary A.2 and Proposition A.3 to prove our main results.

Proof of Theorem 4.1

From Corollary A.2, with \((k_{n})\) satisfying (2.8), under the same Skorohod construction as in Proposition A.1, the Hill estimator has the expansion

which leads to

Together with the asymptotic properties of \(M_{k_{n}}^{(2)}\) obtained again from Corollary A.2, this implies that

Thus, the asymptotic unbiased estimator has the expansion, almost surely as \(n\to\infty\),

In the last step, we use the fact that \(\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n}}\to\gamma\; \mbox{a.s.}\) as \(n\to\infty\). Further, the relation \(k_{n}/k_{\rho}\to 0\) implies that \(\frac{\sqrt{k_{n}}\tilde{A}(n/k_{n})}{\sqrt{k_{\rho}}\tilde{A}(n/k_{\rho})}\to0\) as \(n\to\infty\). Thus, according to Proposition A.3 and Cramér’s delta method, we get that as \(n\to\infty\),

Together with the consistency of \(\hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}^{(\alpha)}\), the expansion (A.4) implies that as \(n\to\infty\),

The theorem is proved by using the covariance structure of \((P_{1}^{(1)}, P_{1}^{(2)})\) given in Corollary A.2. □

Proof of Theorem 4.2

Denote \(d_{n}:=k_{n}/(np_{n})\) and \(T_{n}=\frac{(M_{k_{n}}^{(2)}-2\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n}}^{2})(1-\hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}^{(\alpha)})^{2}}{2\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n}}\{ \hat{\rho}_{k_{\rho}}^{(\alpha)}\}^{2}}\). With \(P_{1}^{(\alpha)}\) defined in Corollary A.2, following the lines of the proof of Theorem 4.1, we obtain that under the same Skorohod construction as in Proposition A.1,

as \(n\to\infty\), which implies that \(T_{n}\to0\) a.s. Together with \(\sqrt{k_{n}}\tilde{A}^{2}(\frac{n}{k_{n}})\to0\) as required in condition (2.8), we have the stronger result that as \(n\to \infty\),

Consider the expansion

The third order condition in (2.6) implies that as \(n\to\infty\),

The limit relation in (A.6) further implies that as \(n\to\infty\),

Combining (A.6) with condition (2.8), we get that \(I_{4}\to0\) and \(I_{5}\to0\) as \(n\to\infty\). Next, from (A.5), we get that \(I_{2}\to0\) and \(I_{3}\to0\;\mbox{a.s.}\), as \(n\to\infty\).

Lastly, we deal with the term \(I_{1}\). Denote the limit of \(\sqrt {k_{n}}(\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n},k_{\rho},\alpha}-\gamma)\) as \(\Gamma\). Then we have that as \(n\to\infty\),

which yields \(\frac{1}{\log d_{n}}d_{n}^{\hat{\gamma}_{k_{n},k_{\rho},\alpha }-\gamma}\to0\;\mbox{a.s.}\) Together with the facts that \(T_{n}\to0\; \mbox{a.s.}\) and

as \(n\to\infty\), we get that \(I_{1}\to\Gamma\;\mbox{a.s.}\) as \(n\to \infty\). The theorem is proved by combining the limit properties of the five terms in the expansion. □

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

de Haan, L., Mercadier, C. & Zhou, C. Adapting extreme value statistics to financial time series: dealing with bias and serial dependence. Finance Stoch 20, 321–354 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00780-015-0287-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00780-015-0287-6